Review Article | Open Access

Non-Histone Chromatin Protein Dysregulation: The Oncogenic Role of HMGB1 and Its Redox States in ccRCC Inflammation and Genome Instability

Betty AlexDepartment of Pathology, Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center, Box980662 1101 E, Marshall street Richmond, VA 23298-0662, Virginia, USA.

Correspondence: Betty Alex (Department of Pathology, Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center, Box980662 1101 E, Marshall street Richmond, VA 23298-0662, Virginia, USA; Email: baalex@outlook.com).

Annals of Urologic Oncology 2025, 8(4): 188-199. https://doi.org/10.32948/auo.2025.12.07

Received: 06 Oct 2025 | Accepted: 10 Dec 2025 | Published online: 22 Dec 2025

HMGB1 is upregulated in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma (ccRCC), the gold standard for RCC diagnosis, where it is often found overexpressed and mislocalized to cytoplasm as wells as being posttranslationally modified, enhancing protumorigenic microenvironment. Hyperactivated HMGB1 drives chronic inflammation, autophagy dependent tumor survival, immune suppression and angiogenesis and genomic instability that links nuclear malfunction to the extracellular cascade in ccRCC progression. Such an orchestration involving redox-mediated HMGB1 signaling is both pro-tumoural inflammatory and anti-genomic maintenance.

Therapeutically, the blockade of HMGB1's redox status, its interaction with receptors or autophagy-associated function can be promising strategies to control growth and sensitize treatment. Additionally, the expression of HMGB1 forms, their cellular localization, and redox state in circulation are potential prognostic and predictive biomarkers. Here we provide an in-depth discussion on the molecular mechanisms related to HMGB1 deregulation in promoting the pathogenesis of ccRCC, and shed light on potential translational applications for clinical intervention.

Key words HMGB1, clear cell renal cell carcinoma, redox regulation, tumor microenvironment, genomic instability

The expression of HMGB1 was initially discovered in the 1970s because it is one of the abundant non‑histone chromosomal proteins with high electrophoretic mobility and DNA binding ability without regard to its sequence [5]. HMGB1 is a small protein of about 215 amino acids with a highly conserved two-box DNA‑binding domain (A‑box and B‑box) and an acidic C terminus, which has been suggested to affect interaction with nucleic acids and proteins [6]. This architecture of HMGB1 accounts for its primary biological role as a DNA chaperone, which can make it insert in minor grooves coiling the double helix and promote nucleoprotein assembly, disassembly and reorganisation, such as those required for transcription, replication, recombination and repair [7]. HMGB1 in the nucleus interacts with various transcription factors, chromatin modifiers and DNA repair proteins, regulating genome protection activities related to genomic stability and gene expression [5]. Due to these vital activities, HMGB1 is considered a member of the non‑histone chromatin‑associated proteins involved in the generation of open/accessible chromatin, which has an important implications for cellular responses to stress and neoplastic transformation [8].

In addition to its nuclear functions, HMGB1 is a prototypical example of a molecule with highly context- and localization-dependent function. In response to cellular stress, injury or activation, HMGB1 can move from the nucleus into the cytoplasm and be released into extracellular environment [9]. Its translocation is critical regulated by several PTMs such as acetylation, phosphorylation, methylation and redox adjustment that modulate its nuclear retention, cytoplasmic localization, and secretion [10]. Importantly, acetylation on lysine residues located within the nuclear localization sequences prevents efficient HMGB1 translocation to the nucleus and induces redistribution of this protein to cytoplasm [11]. Moreover, methylation at some residues (like lysine 112) can affect DNA-binding activity and favor relocation as has been shown in malignant tissues including ccRCC [12]. Through direct interaction with Beclin‑1 and other autophagy‑associated proteins, cytoplasmic HMGB1 also plays a critical role in the regulation of autophagy that determines cell fate decision between survival and death under metabolic crisis and therapy [13]. Released HMGB1 from necrotic cells, and actively secreted HMGB1 by immune cells, also locates HMGB1 at the crossroads of cell death, damage signaling and immune responses [14].

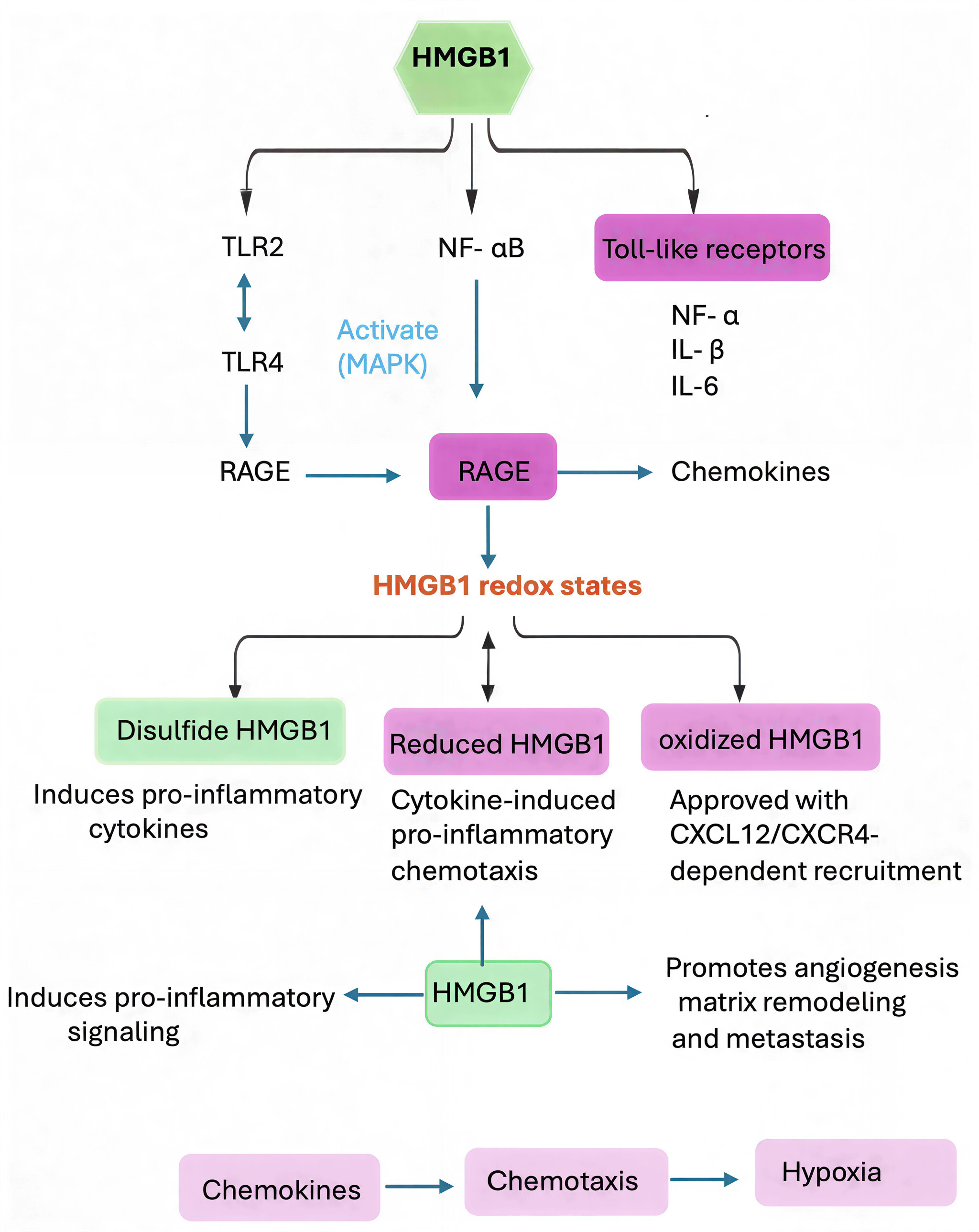

An important and distinctive feature of HMGB1 biology is its redox sensitivity. This protein has three highly conserved cysteine residues (C23, C45 and C106) whose redox state determines the extracellular bioactivity of HMGB1 [15]. In its completely reduced state, with all three cysteines containing a thiol group (HMGB1), it has chemotactic proterties by associating with the chemokine CXCL12 and initiating cellular recruitment via receptor CXCR4 [16]. In its partially oxidized state, in which C23 and C45 are involved in intramolecular disulfide meanwhile C106 is reduced (disulfide HMGB1), the protein induces pro‑inflammatory cytokine release via the Toll‑like receptor 4 (TLR4/MD2) pathway [17]. Terminal oxidation (sulfonyl HMGB1) abrogates both chemotactic and cytokine‑inducing activities. This redox‐mediated regulation endows HMGB1, acting as a contextual alarmin-a damage‑associated molecular pattern (DAMP) operating certain immune and inflammatory circuits in relation to oxidative milieu, which provides its central role of mediator in inflammation and the host response. The relevance of these redox variations is especially applicable to cancer since the tumor microenvironment exhibits oxidative stress, hypoxia, and infiltrating immune cells with the ability to modulate redox [18].

HMGB1 has paradoxical but interrelated functions in cancer. Nuclear HMGB1 is involved in DNA repair and chromatin remodeling, and helps to maintain genomic stability as a tumor‑suppressive activity under no pathological conditions [5]. However, abnormal regulation of this protein can lead to genome damage, parache inflammation and oncogenesis through compromised genome maintenance by expression switch, PTMs, subcellular missite place-ment or chronic release [19]. In fact, cand concomitant partial relocalization to the cytoplasm associated with high tumor grade [20]. Mass spectrometry analysis of ccRCC samples revealed methylation at Lys112 of HMGB1, implying that its DNA-binding characteristics and localization are also epigenetically regulated [21]. These modifications may weaken its nuclear functions and promote extracellular and cytoplasmic signaling activities, thereby promoting inflammation/immunity and tumorigenesis.

The extracellular function of HMGB1 is as a pro‑inflammatory cytokine, which is primarily mediated by interacting with pattern recognition receptors (i.e., TLR2, TLR4 and the Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products; RAGE) [4]. Binding to these receptors activates signalling pathways downstream of, for example, NF‑κB and mitogen activated protein kinases (MAPK), leading to the production of pro‑inflammatory cytokines and chemokines [22]. Chronic activation of such pathways leads to a chronic-inflammation milieu in the tumor microenvironment (TME) that can be important for promoting angiogenesis, inhibiting an effective anti‑tumor immune response and enhancing tumor growth and metastasis [23]. In ccRCC, a tumor characterized by its abundant immune infiltrate and altered inflammatory signaling activity, this HMGB1‑induced inflammation is expected to have a profound impact on the composition of the immune landscape, as well as immune checkpoint responses and responsiveness to immunotherapies [24].

Additionally, that HMGB1 is implicated in autophagy and the cellular decisions about survival or apoptosis demonstrate its role also for effects of therapies [25]. Autophagy may have a dual role in cancer cells: during certain conditions, it could lead to cell death; and under stress, such as nutrient deprivation or exposure to cytotoxic agents, it might give them survivorship [26]. HMGB1 interacts with Beclin‑1 other autophagy exogenous inducers to enhance autophagy may facilitate therapy resistance and tumor survival. The HMGB1 mediated crosstalk control of these processes also highlights how a chromatin protein dysregulation can impact variety of oncogenic modes [27].

Taken together, these observations reveal HMGB1 as a protein of dichotomous natures being involved in both genome integrity and stress responses, immune modulation and inflammation [5]. In ccRCC-a complex tumor characterized by multifaceted genomic and metabolic alterations and interactions with the immune microenvironment-HMGB1 deregulation at expression, localization (nuclear or cytoplasmic), PTMs, redox state site levels makes it a candidate both for driving oncogenic processes as well as for being recognized as a potential biomarker or therapeutic target [24]. As it lies at the nexus of control of chromatin and inflammation, elucidation of the mechanism by which HMGB1 contributes to ccRCC is essential for understanding the integrated biology of this disease and developing new interventions [28].

HMGB1 is one of the most evolutionarily conserved non-histone chromatin proteins, possessing 215 amino acids, including two DNA-binding HMG-box domains (A-box, B-box) and a negatively charged C-terminal acidic tail [29]. The 3 alpha-helices which define the structure of the HMG-box domains give an L-shaped fold that permits HMGB1 to bind within the minor groove of DNA and introduce sharp bends [30]. This DNA bending capacity is essential for the function of HMGB1 as a DNA chaperone, which can promote assembly and accessibility of protein–DNA complexes such as transcription factors and DNA repair enzymes [31]. HMGB1’s acidic tail alters its ability to bind DNA and regulates the affinity for it, but also maintains protein-protein interactions within chromatin structures so that the dynamics of chromatin reorganization can be finetuned [5]. Furthermore, the tail serves as an autoinhibitory element controlling HMGB1 DNA-binding function in a signal-dependent manner, which highlights its ability to tailor genomic activities to specific physiological conditions [32].

In the nucleus, HMGB1 is involved in preserving chromatin structure and genome integrity. It activates transcription by binding to promoters and recruiting other factors, such as general transcription factors, to form a preinitiation complex [5]. HMGB1 also contacts core histones, regulating nucleosome sliding and spacing, and relativeloads chromatin. In addition to transcription, HMGB1 works in DNA replication by stabilizing replication forks and binding origin recognition complexes. Its involvement in the V(D)J recombination of immune cells also demonstrates its flexibility to facilitate specific genomic alterations [5, 33]. Also, HMGB1 acts as a docking scaffold for DNA repair complexes promoting the cross-recruitment of nucleotide excision repair (NER), base excision repair (BER) and double strand break (DSB) factors at sites of damage. Such interactions are critical for timely cell repair after lethal lesions, to prevent chromosomal abnormalities and to maintain genomic integrity, emphasizing the central role of HMGB1 as a guardian of the genome [34, 35].

Recent studies have also shown that the DNA-binding activity of HMGB1 is modulated by its subcellular localization. For example under stress conditions like oxidative damage, DNA alkylation or hypoxia the interaction of HMGB1 with chromatin might change resulting in redistribution of this protein within the nucleus or translocation to the cytoplasm [36]. Existence of such a dynamic control equips HMGB1 as a sensor of genomic stress, integrates modifications in nuclear architecture to downstream signalcontacts during inflammation and autophagy. In cancer cells, such as ccRCC, these controls are frequently perturbed and participate in the development of chromatin instability, transcriptional reprogramming and acquisition of an oncogenic phenotype.

Post-translational modifications and cellular localization

HMGB1 is subject to an extensive range of PTMs that regulate its nuclear, cytoplasmic, and extracellular functions. Such modifications are, for example lysine acetylation, arginine and lysine methylation, serine/threonine phosphorylation as well as tyrosine phosphorylation ADP-ribosylation ubiquitination oxidative modifications [37]. Post-translational modifications (PTMs) regulate HMGB1’s nuclear retention, DNA-binding activity, and the potential of it to translocate into cytoplasm or be released outside cell. For instance, overacetylation of the lysine residues in nuclear localization signals (NLS) decreases HMGB1 binding to chromatin and facilitates it being exported via CRM1 pathway. Likewise, methylation of lysine (detected in tumors including ccRCC) decreases binding to nuclear DNA and promotes cytoplasmic retention, hence the execution of its non-nuclear roles, e.g. induction of autophagy or modulation of cytokines.

HMGB1 phosphorylation also plays a role in nuclear-cytoplasmic translocation of this protein. Kinases initiated by cellular stress or inflammatory signaling may phosphorylate the serine or threonine residues of NLSs, weakening nuclear retention [38]. Moreover, ADP‐ribosylation may act cooperatively with acetylation in the enhancement of active secretion from immune cells, hence associating HMGB1 PTMs to its extracellular signaling activities. Such post-translational changes represent a molecular switch, which HMGB1 uses to convert from a nuclear genome housekeeper into a cytoplasmic or extracellular DAMP, demonstrating the duality of HMGB1 in homeostasis versus stress [39].

The cross talk of PTMs and cellular localization in cancer is a special concern. Deviations in post-translational modifications of HMGB1, that have been recorded in ccRCC and other malignancies, are involved in deregulated inflammation, modified autophagy processes and apoptosis resistance. For example, HMGB1 in cytoplasm of tumor cells engages autophagy machinery with resultant survival under hypoxic and nutrient-poor condition [40]. The phosphorylated TLR4 can then dampen HMGB1 and cytokine release from macrophages through binding and sequestration of this extracellular nucleic acid-binding protein, released by stressed or necrotic tumor cells acting on pattern recognition receptors (RAGE or TLRs), which maintains a pro-tumorigenic inflammation [41]. For these reasons, PTMs control the localization of HMGB1 as well as help maintain a dynamic functional character that strikes a balance between genome fidelity versus immune responses and survival (Table 1) [42].

Redox regulation of HMGB1 activity

The three conserved cysteines of HMGB1 (C23 and C45 on the A-box and C106 on the B-box) confer an intrinsic redox sensitivity to HMGB1 barcode for its outside-in signaling properties [43]. The redox state of these two cysteines is a key molecular switch that controls the biological function of HMGB1 and immune modulation. HMGB1 in the fully reduced state (all-thiol form) preserves its chemotactic activity through heterocomplex formation with CXCL12, which promotes the recruitment of immune cells bearing the CXCR4 receptor into injury or inflamed sites. In this context, HMGB1 primarily functions as a pro-migratory factor during tissue repair and leukocyte trafficking [44].

Disulfide HMGB1, with an intramolecular bond between C23 and C45 while C106 is in the thiol state, can mediate cytokine induction through stimulation of the TLR4/MD-2 complex or engagement of RAGE. This is pro-inflammatory form which activates the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways and produces TNF-α, IL-1β, and other cytokines. The continued existence of disulfide HMGB1 in the tumor microenvironment, especially in ccRCC, maintains persistent low-grade inflammation which migrates immune cells and promotes pro-survival signaling to drive tumor growth and escape from the host immune response [45].

In contrast, completely oxidized HMGB1 (sulfonylated) is biologically display chemotactic and cytokine-inducing activities are not present with both forms two of which enumerated are used as markers resolution of inflammation and oxidative stress. Loss of redox equilibrium in the tumor microenvironment may also tipadisulfide nature favored for HMGB1, that resulting as persistent, supports a pro-tumorigenic context [46]. In the intracellular environment, redox regulation also contributes to the influence on HMGB1’s nuclear function: oxidative stress leads to conformational changes with decreased DNA binding, increased release from chromatin and, consequently, cytoplasmic translocation. These results emphasize that redox regulation is a subtle modulator orchestrating the pleiotropic functions of HMGB1 and interlinking oxidative stress, immune modulation and tumorigenesis (Table 2) [47].

|

Table 1. HMGB1 post-translational modifications and functional consequences. |

|||

|

PTM type |

Residues / Site |

Effect on HMGB1 |

Functional consequence |

|

Acetylation |

Lysines in NLS |

Reduces DNA binding, promotes nuclear export |

Facilitates cytoplasmic accumulation and extracellular release |

|

Methylation |

Lys112 |

Alters DNA-binding affinity |

Promotes cytoplasmic localization, impairs nuclear genome maintenance |

|

Phosphorylation |

Serine / Threonine |

Modulates nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling |

Enhances translocation under stress or inflammatory conditions |

|

ADP-Ribosylation |

Lys / Arg residues |

Facilitates secretion |

Enables extracellular DAMP signaling |

|

Oxidation (Redox) |

C23, C45, C106 |

Determines chemotactic vs. cytokine-inducing activity |

Regulates inflammation, immune response, and tumor-promoting effects |

|

Ubiquitination |

Lysine residues (Lys42) |

Targets HMGB1 for proteasomal degradation |

Regulates HMGB1 stability and abundance; limits extracellular release |

|

Sumoylation |

Lysines (Lys180) |

Influences subcellular localization and DNA repair interactions |

Modulates transcriptional regulation and genomic stability |

|

Glycosylation |

Potential sites under investigation |

May affect HMGB1 stability and receptor binding |

Hypothesized to alter extracellular signaling and inflammatory potency (emerging research) |

|

Nitrosylation |

Cysteine residues (C23, C45) |

Modifies redox state and disulfide bond formation |

Fine-tunes chemokine vs. cytokine activity; may protect against over-oxidation |

|

Proteolytic cleavage |

C-terminal acidic tail removal |

Enhances pro-inflammatory activity |

Increases HMGB1’s affinity for TLR4 and RAGE receptors; amplifies immune response |

|

Lactylation |

Lysine residues |

Emerging role in inflammation and gene regulation |

Links metabolic state to immune function; potential impact on HMGB1 transcriptional activity |

|

Table 2. Redox forms of HMGb1 and their biological activities. |

||||

|

HMGB1 redox form |

Cysteine configuration |

Extracellular activity |

Primary function |

Tumor relevance in ccRCC |

|

Fully reduced (all-thiol) |

C23-SH, C45-SH, C106-SH |

Chemotaxis |

Leukocyte recruitment via CXCL12/CXCR4 |

Promotes immune cell migration to TME |

|

Disulfide |

C23-C45 bond, C106-SH |

Cytokine induction |

Activates TLR4/RAGE, induces NF-κB signaling |

Sustains chronic inflammation, promotes tumor survival |

|

Fully oxidized (sulfonyl) |

C23-SO3H, C45-SO3H, C106-SO3H |

Inactive |

Resolution of inflammation |

Loss of chemotactic and cytokine activity, anti-tumor effects |

|

Terminal oxidation (sulfinic) |

C23-SO2H, C45-SO2H, C106-SO2H |

Immune-modulatory (context-dependent) |

May promote clearance or tolerogenic signaling |

Emerging role in immune evasion; potentially induces regulatory immune responses that suppress anti-tumor immunity in the TME |

|

Mixed disulfide (glutathionylated) |

C23-S-SG, C45-S-SG, or C106-S-SG |

Modulated inflammatory signaling |

Attenuates TLR4 activation, alters HMGB1-receptor interactions |

May protect tumor cells from excessive immune-mediated damage; potential redox buffer in hypoxic ccRCC tumors |

|

Nitrosylated |

C23-SNO, C45-SNO, C106-SNO |

Regulated chemotaxis & inflammation |

Fine-tunes redox signaling; can transiently inhibit disulfide bond formation |

Links nitrosative stress to HMGB1 function; may influence hypoxia adaptation and treatment response in VHL-deficient ccRCC |

HMGB1 is an essential factor involved in the preservation of genomic stability through its direct effect on chromatin structure and mediating DNA repair. In the nucleus, HMGB1 associates with DNA regions that are unwound or damaged and promotes their bending into conformations accessible to repair enzymes. This bent-DNA functions to increase the recruitment and stabilize repair complexes involved in BER, NER and double stranded break (DSB) repair pathways [48]. The combination of HMGB1 with DNA glycosylases, endonucleases and ligase guarantees specific recognition and high efficiency repair. Dysregulation of HMGB1 results in increased DNA damage, chromosomal fragmentation and sensitivity to genotoxic stress, thus revealing a novel function of HMGB1 in maintaining genomic integrity [49].

HMBG1 is an important factor for chromatin remodeling, not just as a part of direct DNA repair. Through interacting with and competing with histone H1, HMGB1 has been shown to abet chromatin flexibility and nucleosome sliding which in turn allows transposition of transcription factors onto target genes [50]. This architectural role is necessary to coordinate the ability of DNA repair and replication in time and space, even more so as dense nucleosome packing commonly occurs during factor recruitment within heterochromatin domains. HMGB1 complexes with chromatin remodelers including the SWI/SNF and the INO80 complexes to cooperatively induce nucleosome repositioning and repair complex assembly [51]. These intimate connections highlight the pivotal role of HMGB1 in keeping chromatin organization and genomic stability (Figure 1).

It is worth noting that the nuclear functions of HMGB1 are not only limited to specialized DNA rearrangement and telomere control. It plays a role in V(D)J recombination of the immune system, and promotes antigen receptor diversity while inhibiting non-homologous end joining that could cause genomic instability [52]. HMGB1 is also involved in the protection of telomeres where it binds to telomeric DNA and components of shelterin, thereby contributing to telomerase length homeostasis and protecting against chromosomal end-to-end fusions [53]. Disruption of HMGB1 function and/or its translocation into the cytoplasm causes these events to go awry, where instead telomeres erode, chromosomes missegregate, and cancer risk increases [54]. These findings underscore a novel role of HMGB1 as protector of genome stability during physiological and stress conditions, in addition to its function as structural chromatin protein.

Influence on genomic stability and tumor suppression

HMGB1 is also involved in multiple mechanisms of maintaining the stability of the genome and suppression of tumour, being its interaction with key enzymes related to DNA topology, replication and chromosome segregation one of them. Of note, HMGB1 associates with topoisomerase IIα to resolve DNA supercoils and inhibit ectopic recombinations at the time of replication. HMGB1 stabilizes replication forks and promotes resolution of stalled forks, inhibiting the accumulation of replication-associated DNA damage that is a cause of mutagenesis and chromosomal instability [55]. In addition, HMGB1 modulates telomerase, enhancing the length of chromosome ends (telomeres), and protecting these structures from erosion and cellular senescence.

HMGB1 also interacts with tumor suppressor pathways such as p53 and RB to regulate damage-dependent checkpoints and cell cycle fidelity [56]. By direct or indirect contacts, HMGB1 regulates the expression of DNA repair genes and promotes apoptosis or cell cycle arrest in presence of damage that is beyond repair. HMGB1 loss, or inappropriate localization outside the nucleus, weakens these tumor suppressive processes that can otherwise prevent mutational accrual and oncogenic progression. Given that in the setting of ccRCC, with its frequent mutations in chromatin regulators (PBRM1, SETD2, BAP1 ) also HMGB1 dysregulation could potentially additively affect genome fidelity and accentuate the impact of these alterations on tumor evolution [57].

There is also growing evidence that HMGB1 plays a role in preventing oxidative DNA damage. Its DNA binding and bending activity may promote access of antioxidant damage repair enzymes to the damaged bases, and by binding to chromatin remodeling factors, it could enable its efficient repair even in condensed regions of chromatin. In ccRCC the oxidative tumor microenvironment could influence HMGB1 dysfunction with consequent DNA damage to remain on active chromatin, unstable chromosomes driving mutational burden. Collectively, HMGB1's nuclear roles form an essential bridge integrating chromatin dynamics, DNA repair accuracy, telomere integrity and tumor inhibition functions. Dysfunction of these processes is now emerging as a major contributor to the pathobiology and behavior of ccRCC, and constitutes an underpinnning in our proposed model for HRG6-induced upregulation of HMGB1, which clearly emerges from our study as not only being a biomarker for genomic stress that foreshadows ccRCC evolution but also a clinically useful target.

Figure 1. HMGB1’s nuclear roles in genomic stability. HMGB1 is a master gene to maintain stability of the genome inside the nucleus. It enables DNA damage repair [including base excision repair and nucleotide-excision repair (NER) as well as double-strand break (DSB)] while promoting chromatin remodeling through H1 and SWI/SNF complexes, telomere maintenance, and transcriptional control. In ccRCC, perturbation of nuclear HMGB1 by mislocalization or post-translational modifications disrupts these activities during normal cell growth and confers support for genomic instability and tumor progression.

Figure 1. HMGB1’s nuclear roles in genomic stability. HMGB1 is a master gene to maintain stability of the genome inside the nucleus. It enables DNA damage repair [including base excision repair and nucleotide-excision repair (NER) as well as double-strand break (DSB)] while promoting chromatin remodeling through H1 and SWI/SNF complexes, telomere maintenance, and transcriptional control. In ccRCC, perturbation of nuclear HMGB1 by mislocalization or post-translational modifications disrupts these activities during normal cell growth and confers support for genomic instability and tumor progression.

HMGB1 acts as a prototypical DAMP upon its release into the extracellular space passively (from necrotic or damaged cells) or actively in response to stressful conditions or inflammatory signals from immune cells [58]. Post-release, HMGB1 associates with several pattern recognition receptors such as Toll-like receptor (TLR2 and TLR4) and receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE), resulting in a signalling cascade [59]. These contacts lead to the activation of NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways, which ultimately induce the transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 and chemokine genes that facilitate leukocyte recruitment. The function of extracellular HMGB1 is strongly linked to its redox form; disulfide bond-containing (C23–C45) and reduced (C106) double chain form of HMGB1 induces potent cytokine-stimulating activity, whereas all-thiol structure HMGB1 mainly mediates chemotaxis and cell migration [60, 61]. The completely oxidized form of HMGB1 is mostly inactive, which could be a regulatory mechanism to prevent uncontrolled inflammation.

The release of HMGB1 as a DAMP is not only inevitable course for damaged cells, it is also a programmed process that initiates and augments tumor-promoting inflammation [62]. In the case of ccRCC, the TME is abundant in cells that are hypoxic and metabolically stressed, making it favorable for HMGB1 release. Upon release into the extracellular space, HMGB1 also sets up paracrine and autocrine signaling relays which activate local immune effector cells, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts to drive inflammation. This network can stimulate angiogenesis, induce extracellular matrix turnover and facilitate metastatic spread. And disulfide redox HMGB1 activates TLR4 on dendritic cells and macrophage to stimulate persistent cytokine secretion that results in the chronic inflammatory environment usually present in ccRCC tumors.

In addition to classical cytokine induction, extracellular HMGB1 is also a chemoattracting molecule and has been shown to guide the migration of immune and stromal cells to the TME [63]. By complexing with chemokines, including CXCL12, HMGB1 directs CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4)-dependent recruitment of leukocytes, such as regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells [64]. The dual ability of the molecule to induce inflammation and to attract cells, rather than put it into a specific cellular context, makes HMGB1 a key regulator of immune–tumor interactions that links tissue damage, oxidative stress and tumor-promoting inflammation in an evolving loop (Figure 2).

Chronic inflammation and tumor progression

Chronic HMGB1-induced inflammation is a strong promoter for the tumorigenesis of ccRCC [65]. Long-term activation of NF-κB and MAPK signals downstream of extracellular HMGB1, driving pro-tumorigenic cytokines such as IL-6/IL-8 and VEGF that support angiogenesis and establish a permissive environment for tumor progression [66]. Persistent HMGB1 signalling further contributes to immunosuppression by mobilizing Tregs, M2-polarized macrophages and other immunosuppressive cells to the TME and concurrently suppressing cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) and natural killer (NK) cell functions [67]. This immune escape contributes to the ccRCC pathogenesis by which tumor cells avoid immunorecognition.

In chronically inflamed microenvironments HMGB1 enhances carcinogenesis not only through the modulation of immune function but also by promoting genomic instability. ROS produced by inflammatory and tumor cells cause the microenvironment to be pro-oxidative that may result in DNA damage, telomere shortening, and chromosomal instability [68]. The effects are further intensified by the inflammatory, tissue-remodeling positive feedback loop created by HMGB1, as damaged cells secrete more HMGB1 and continue to drive inflammation and tissue remodeling. This cycle promotes both tumor progression and heterogeneity, and leads to resistance to therapy and disseminated disease. The combinatorial impact of persistent cytokine signaling, oxidative damage and immune suppression emphasizes the prominence of HMGB1 as an epicenter that connects inflammation to oncogenesis in ccRCC [69].

Additionally, HMGB1 signaling affects the stromal and vascular elements of the TME. It activates endothelial cell expression of adhesion molecules, increases vascular permeability and stimulates angiogenic sprouting leading to a highly vascularized microenvironment conducive for rapid tumor expansion. Cancer associated fibroblasts activated by HMGB1 produce extracellular matrix proteins and growth factors which promote the growth, invasion, and metastasis of tumor cells. Therefore, HMGB1 is a master switch that orchestrate both cellular and stromal compartments of TME to where it conscriptes inflammation with construction for tumor growing.

Autophagy, apoptosis, and cell survival

Cytoplasmic HMGB1 is important to modulate autophagy, a crucial survival mechanism especially under metabolic stress as occurs in ccRCC [70]. HMGB1 directly interacts with Beclin-1, the central stimulator of autophagy that overcomes its inhibitory Bcl-2 binding to induce autophagosome formation [71]. This crosstalk can also promote the clearance of injured organelles and aggregation proteins, which contributes to cellular homeostasis balance and anti-apoptosis. In cancer cells, HMGB1-induced autophagy promotes the survival of this tumor in response to nutrient deprivation, hypoxia and anticancer agents [72].

Apart from autophagy, HMGB1 also drives apoptotic pathways by regulating signaling pathways, such as ERK1/2, JNK and PI3K/AKT. By stimulating ERK1/2 signaling, HMGB1 promotes proliferation and survival and suppresses pro-apoptotic pathways to enable ccRCC cells to resist genotoxic and metabolic stress [73, 74]. Cytosolic HMGB1 crosstalks with mitochondria as well, adjusting mitochondrial membrane potential and reactive oxygen species production in favour of cell survival rather than apoptotic programmed cell death [75].

The dual control of autophagy and apoptosis by HMGB1 illustrates an intricate strategy for cancer cells to hijack a nuclear protein into cytoplasmic survival apparatus [76]. In ccRCC, these mechanisms promote the survival of tumor cells in a hostile environment, avoid immune-based elimination and resist to common treatments. Furthermore, the extracellular secretion of HMGB1 by stressed tumor cells potentiates TME reprogramming and inflammatory signaling pathway activation, bridging intracellular survival pathways with intercellular cross-talk. This dual intra- and extracellular functionality emphasizes HMGB1 as a critical node in the cascade between stress response, inflammation and tumour advancement.

Figure 2. HMGB1 in the ccRCC tumor microenvironment as a damage associated molecular patterns (DAMP): signaling and immune modulation. Extracellular HMGB1 is a typical DAMP in ccRCC involved in cancer-inflammation and cancer-immune escape. In its disulfide HMGB1 form, this DAMP binds to TLR4 and RAGE receptors with the induction of pro-inflammatory NF-κB and MAPK pathways (such as TNF-α, IL-6). HMGB1 forms a complex with CXCL12 to induce immune cells recruitment through their CXCR4 in its fully reduced form. These processes maintain a state of chronic inflammation, support angiogenesis, draw immunosuppressive cells (Tregs, MDSCs), and foster an enriched environment that allows cancer to grow and spread.

Figure 2. HMGB1 in the ccRCC tumor microenvironment as a damage associated molecular patterns (DAMP): signaling and immune modulation. Extracellular HMGB1 is a typical DAMP in ccRCC involved in cancer-inflammation and cancer-immune escape. In its disulfide HMGB1 form, this DAMP binds to TLR4 and RAGE receptors with the induction of pro-inflammatory NF-κB and MAPK pathways (such as TNF-α, IL-6). HMGB1 forms a complex with CXCL12 to induce immune cells recruitment through their CXCR4 in its fully reduced form. These processes maintain a state of chronic inflammation, support angiogenesis, draw immunosuppressive cells (Tregs, MDSCs), and foster an enriched environment that allows cancer to grow and spread.

HMGB1 is overexpressed in ccRCC tumors compared to adjacent normal renal parenchyma and its expression increases significantly with tumor grade and stage. Immunohistochemical examination demonstrates increased nuclear HMGB1 accompanied by its considerable cytoplasmic location, indicating that HMGB1 translocation between the nucleus and the cytoplasm is a trait of tumor malignancy [77]. The translocation of HMGB1 to distal endplates disrupts the canonical nuclear activities of HMGB1, such as DNA repair, chromatin remodelling, and genomic stability. Mechanistically, post-translational modifications including methylation of lysine 112 regulate DNA binding and trigger cytoplasmic relocation of HMGB1, by dissociating its genome defense roles from both extracellular signaling or intracellular downstream actions. This aberrant localization indicates the transition of Pol δ function from maintenance of nuclear genome to activation of an oncogenic stress response [78].

Cytoplasmic and extracellular HMGB1 in ccRCC not only promotes autophagy and survival signaling, but also sustains a pro-inflammatory tumor microenvironment [79, 80]. The degree of cytoplasmic translocation is frequently associated with enhanced tumor vascularization, immune cell infiltration and cytokine production, highlighting its role as a pleiotropic oncogenic factor. Importantly, the mislocalization of HMGB1 might additionally crosstalk with other dysregulated chromatin modifiers in ccRCC, resulting in more severe transcriptional reprogramming and genomic instability, and thereby promoting both tumor aggressiveness and resistance to conventional treatment.

Interaction with RAGE and autophagy in ccRCC

In ccRCC, HMGB1 interacts with RAGE and then instigates their downstream signaling pathways to regulate cellular survival, growth and autophagy [79]. HMGB1 and RAGE interaction induce autophagy markers namely LC3-II and Beclin-1 promoting autophagosome generation leading to the more efficient clearance of damaged organelles, proteins. This mechanism contributes to tumor cell survival in the setting of metabolic stress, hypoxia and cytotoxic therapies that are typical of the ccRCC microenvironment. By improving autophagy, HMGB1-RAGE signaling allows tumor cells to survive under nutrient-deplete conditions and oxidative stress, which in turn empowers the cells and makes them develop resistance against apoptosis [81].

HMGB1-RAGE complex can also promote important oncogenic pathways such as PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK, which regulate proliferation, cellular migration and metabolic reprogramming besides autophagy. Indeed, induction of up-stream pathways by extracellular HMGB1 further increases and maintains the pro-survival signaling which in turn leads to increased expression/secretion of HMGB1. HMGB1, RAGE and its downstream effectors interact in such a manner as to form a self-perpetuating network, which potentiates tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis of ccRCC patients with subsequent implications for the critical role that HMGB1-RAGE signaling plays by not only participating in cellular adaptation but also driving the expansion of neoplastic disease.

Impact on tumor immunity and microenvironment

HMGB1 plays an important role in sculpting the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) of ccRCC and regulating the immune reaction and cytokine networks [82]. Extracellular HMGB1 increases the expression of immunosuppressive cytokines, such as IL-10 and TGF-β, which recruits and activates Tregs and MDSCs. These immunologic changes decrease the activity of CTL and NK cells, which permits escape from immune surveillance by tumor cells [83]. By dynamically reshaping the proportion of PIMC and AIMC, HMGB1 established a permissive milieu associate with tumor survival, immune evasion and disease advancement.

As well as modulation of the immune system, HMGB1 has effects on stromal and vascular components in the TME. Its signaling leads endothelial cells to up-regulate adhesion molecules and VEGF, eventually resulting to angiogenesis and vasculature remodeling, as well as fibroblasts in producing extracellular matrix proteins which contribute to the invasion of tumor [84]. This multi-layered modulation of the TME weaves HMGB1’s inflammatory, autophagic and survival functions, establishing it as a master for ccRCC development. The immunosuppressive and pro-angiogenic implication of dysregulated HMGB1 supported the predictive role of it as well as its therapeutic targeting in ccRCC.

Redox imbalance in ccRCC

Metabolic and hypoxic environment in ccRCC inherently dictates the redox status of HMGB1, favoring variants that can induce inflammation or support cell survival. Extremely high oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the TME convert HMGB1 to its disulfide form, a potent activator for proinflammatory cytokine production through signaling by TLR4 and RAGE [85]. This redox-triggered activation sustains chronic inflammation, recruits immunosuppressive cells and amplifies survival signaling that in turn establishes a feedforward loop driving tumor growth. The disturbance of the HMGB1 redox status consequently influences oncogenic events suggesting that regulation of its activity by reactive oxygen species is relevant for cancer development.

Oxidative stress also disrupts the nuclear functions of HMGB1. The loss of affinity for DNA-binding, cytoplasmic translocation as well as lacking ability to participate in chromatin remodeling have been implicated in the generation of genomic instability and accumulation of DNA damage [86]. In such ccRCC-specific context of enhanced extracellular signaling and impaired nuclear action, these factors contribute to tumorigenesis at an increased rate related to promote therapy resistance and increased metastatic spread. Thus targeting redox-dependent function of HMGB1 could be an attractive strategy to restore genome stability, while suppressing pro-tumor inflammation.

Targeting HMGB1 redox functions

Since HMGB1’s redox status is a major factor in determining its pro-inflammatory and pro-survival activities, targeting of HMGB1 redox functions represents an attractive therapeutic strategy in ccRCC. Small molecule, peptide or monoclonal antibodies can be developed to specifically targeting the disulfide form of HMGB1; thus, we may prevent chronic inflammation and tumor promoting cytokine signaling [78]. In addition, the antioxidant treatments that can move HMGB1 to the completely oxidized form, which is inactive, may suppress its extracellular activity and nullify feedback circuits to feed the tumor environment. Preclinical experiments showed that chemical intervention with the redox state of HMGB1 can reduce tumor burden, block angiogenesis and increase chemosensitivity in other solid malignancies, suggesting a plausible translational approach for ccRCC treatment [87]. Critically, these interventions may both dampen inflammation and survival signals that could have a two-drug therapeutic advantage.

Inhibiting HMGB1-RAGE/TLR interactions and biomarker potential

Concurrently, HMGB1 has the potential as a translational biomarker. HMGB1 serum concentration, along with patterns of redox forms, might serve as predicted information about the disease course and tumor mass size or responsiveness to treatment, including immune checkpoint inhibitors or anti-angiogenic therapies [91]. Quantitative analysis of longitudinal plasma HMGB1 concentrations might inform individual therapeutic approaches, and examination of the presence and posttranslational modification status of HMGB1 in tumor tissues offers possible perspectives on tumor aggressiveness and resistance to treatment [42]. Therapeutic intervention in combination with biomarker-based patient stratification is likely to comprise an integrated program that are hard to be walked away from ccRCC patients for better outcome.

Outside the nucleus, extracellular HMGB1 serves as a potent damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) by regulating redox-sensitive inflammation, immune cell recruitment and cytokine networks. Especially the disulfide form of HMGB1 increases potentiation of pro-inflammatory signaling through TLRs and RAGE in chronic inflammation, recruitment of immunosuppressive cells, and angiogenesis. Furthermore, cytoplasmic HMGB1 promotes autophagy by binding directly to Beclin-1 and other ATG-related proteins thus promoting tumor cell adaptation in the context of nutrient deprivation, hypoxia, and therapeutic stress. Altogether, these pleiotropic roles place HMGB1 at the center of a network that connects genome instability with inflammation, autophagy and immune evasion in ccRCC.

From a therapeutic point of view, blocking HMGB1 seems an attractive strategy to breakdown these circuits. Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-scavenging agents, receptor-targeting antibodies and the blockade of HMGB1-mediated autophagy are appealing ways to reduce inflammation, genome instability as well as sensitize cancer cells to therapy. Furthermore, the location of HMGB1 molecule in vivo, its posttranslational modification, and its oxidized forms can be used as biomarkers for prognosis of disease progression or responsiveness to therapy that may further lead to personalized treatment. In conclusion, investigation of molecular details of dysregulated HMGB1 in ccRCC offers valuable insights into tumor biology and highlights new therapeutic prospects to benefit patients.

None.

Ethical policy

Non applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this publication.

Author contributions

Betty Alex designed, drafted and revised the article.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Funding

None.

- Grammatikaki S, Katifelis H, Farooqi AA, Stravodimos K, Karamouzis MV, Souliotis K, Varvaras D, Gazouli M: An overview of epigenetics in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. In Vivo 2023, 37(1): 1-10.

- Mazumder S, Higgins PJ, Samarakoon R: Downstream targets of VHL/HIF-α signaling in renal clear cell carcinoma progression: mechanisms and therapeutic relevance. Cancers 2023, 15(4): 1316.

- Liao L, Testa JR, Yang H: The roles of chromatin-remodelers and epigenetic modifiers in kidney cancer. Cancer Genet 2015, 208(5): 206-214.

- Chen Q, Guan X, Zuo X, Wang J, Yin W: The role of high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) in the pathogenesis of kidney diseases. Acta Pharm Sin B 2016, 6(3): 183-188.

- Chikhirzhina E, Starkova T, Beljajev A, Polyanichko A, Tomilin A: Functional diversity of non-histone chromosomal protein HmgB1. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21(21): 7948.

- Santhiya P, Christian Bharathi A, Syed Ibrahim B: The pathogenicity, structural and functional exploration of human HMGB1 single nucleotide polymorphisms using in silico study. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2020, 38(15): 4471-4482.

- Bonaldi T: Mechanistical studies of two functions of HMGB1 protein: facilitation of nucleosome sliding and translocation from the nucleus to the extracellular medium. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Thesis of the Open University 2004.

- Hou H: From DNA Topology to Pubertal Onset: Using Integrative Genomic Approaches to Study Transcriptional Regulation. Doctor of Philosophy Thesis of University of Toronto (Canada) 2019.

- Tang D, Kang R, Zeh HJ, Lotze MT: The multifunctional protein HMGB1: 50 years of discovery. Nat Rev Immunol 2023, 23(12): 824-841.

- Tang Y, Zhao X, Antoine D, Xiao X, Wang H, Andersson U, Billiar TR, Tracey KJ, Lu B: Regulation of posttranslational modifications of HMGB1 during immune responses. Antioxid Redox Signal 2016, 24(12): 620-634.

- Wang Y, Wang L, Gong Z: Regulation of acetylation in high mobility group protein B1 cytosol translocation. DNA Cell Biol 2019, 38(5): 491-499.

- Lai Y, Li Z, Lu Z, Zheng H, Chen C, Liu C, Yang Y, Tang F, He Z: Roles of DNA damage repair and precise targeted therapy in renal cancer. Oncol Rep 2022, 48(6): 1-12.

- Kang R, Livesey KM, Zeh I, Herbert J, Loze MT, Tang D: Metabolic regulation by HMGB1-mediated autophagy and mitophagy. Autophagy 2011, 7(10): 1256-1258.

- Bustin M: At the crossroads of necrosis and apoptosis: signaling to multiple cellular targets by HMGB1. Science’s STKE 2002, 2002(151): pe39-pe39.

- Yang H, Lundbäck P, Ottosson L, Erlandsson-Harris H, Venereau E, Bianchi ME, Al-Abed Y, Andersson U, Tracey KJ: Redox modifications of cysteine residues regulate the cytokine activity of HMGB1. Mol Med 2021, 27(1): 58.

- Yang H, Antoine DJ, Andersson U, Tracey KJ: The many faces of HMGB1: molecular structure-functional activity in inflammation, apoptosis, and chemotaxis. J Leukoc Biol 2013, 93(6): 865-873.

- Andersson U, Tracey KJ, Yang H: Post-translational modification of HMGB1 disulfide bonds in stimulating and inhibiting inflammation. Cells 2021, 10(12): 3323.

- Janko C, Filipović M, Munoz LE, Schorn C, Schett G, Ivanović-Burmazović I, Herrmann M: Redox modulation of HMGB1-related signaling. Antioxid Redox Signal 2014, 20(7): 1075-1085.

- Wang M, Gauthier A, Daley L, Dial K, Wu J, Woo J, Lin M, Ashby C, Mantell LL: The role of HMGB1, a nuclear damage-associated molecular pattern molecule, in the pathogenesis of lung diseases. Antioxid Redox Signal 2019, 31(13): 954-993.

- Niu L, Yang W, Duan L, Wang X, Li Y, Xu C, Liu C, Zhang Y, Zhou W, Liu J: Biological functions and theranostic potential of HMGB family members in human cancers. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2020, 12: 1758835920970850.

- Angulo JC, Manini C, López JI, Pueyo A, Colás B, Ropero S: The role of epigenetics in the progression of clear cell renal cell carcinoma and the basis for future epigenetic treatments. Cancers 2021, 13(9): 2071.

- Liu T, Li Q, Jin Q, Yang L, Mao H, Qu P, Guo J, Zhang B, Ma F, Wang Y: Targeting HMGB1: a potential therapeutic strategy for chronic kidney disease. Int J Biol Sci 2023, 19(15): 5020.

- Zhao H, Wu L, Yan G, Chen Y, Zhou M, Wu Y, Li Y: Inflammation and tumor progression: signaling pathways and targeted intervention. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2021, 6(1): 263.

- Kruk L, Mamtimin M, Braun A, Anders H-J, Andrassy J, Gudermann T, Mammadova-Bach E: Inflammatory networks in renal cell carcinoma. Cancers 2023, 15(8): 2212.

- Xu T, Jiang L, Wang Z: The progression of HMGB1-induced autophagy in cancer biology. Onco Targets Ther 2018, 12: 365-377.

- Linder B, Kögel D: Autophagy in cancer cell death. Biology 2019, 8(4): 82.

- Tang D, Kang R, Cheh C-W, Livesey KM, Liang X, Schapiro NE, Benschop R, Sparvero LJ, Amoscato AA, Tracey KJ: HMGB1 release and redox regulates autophagy and apoptosis in cancer cells. Oncogene 2010, 29(38): 5299-5310.

- Vladimirova D, Staneva S, Ugrinova I: Multifaceted role of HMGB1: From nuclear functions to cytoplasmic and extracellular signaling in inflammation and cancer. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol 2025, 143: 271-300.

- Lohani N, R Rajeswari M: Dichotomous life of DNA binding high mobility group box1 protein in human health and disease. Curr Protein Pept Sci 2016, 17(8): 762-775.

- Czapla L, Peters JP, Rueter EM, Olson WK, Maher III LJ: Understanding apparent DNA flexibility enhancement by HU and HMGB architectural proteins. J Mol Biol 2011, 409(2): 278-289.

- Kozlova A, Valieva M, Maluchenko N, Studitsky V: HMGB proteins as DNA chaperones that modulate chromatin activity. Mol Biol(Mosk) 2018, 52(5): 637-647.

- Ren W, Zhao L, Sun Y, Wang X, Shi X: HMGB1 and Toll-like receptors: potential therapeutic targets in autoimmune diseases. Mol Med 2023, 29(1): 117.

- Travers AA: Priming the nucleosome: a role for HMGB proteins? EMBO Rep 2003, 4(2): 131-136.

- Liu Y, Prasad R, Wilson SH: HMGB1: roles in base excision repair and related function. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010, 1799(1-2): 119-130.

- Dutta A, Yang C, Sengupta S, Mitra S, Hegde ML: New paradigms in the repair of oxidative damage in human genome: mechanisms ensuring repair of mutagenic base lesions during replication and involvement of accessory proteins. Cell Mol Life Sci 2015, 72(9): 1679-1698.

- Pisetsky DS: The translocation of nuclear molecules during inflammation and cell death. Antioxid Redox Signal 2014, 20(7): 1117-1125.

- Richard SA, Jiang Y, Xiang LH, Zhou S, Wang J, Su Z, Xu H: Post-translational modifications of high mobility group box 1 and cancer. Am J Transl Res 2017, 9(12): 5181-5196.

- Roux PP, Blenis J: ERK and p38 MAPK-activated protein kinases: a family of protein kinases with diverse biological functions. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2004, 68(2): 320-344.

- Andersson U, Tracey KJ, Yang H: Post-Translational Modification of HMGB1 Disulfide Bonds in Stimulating and Inhibiting Inflammation. Cells 2021, 10(12): 3323.

- Su Z, Wang T, Zhu H, Zhang P, Han R, Liu Y, Ni P, Shen H, Xu W, Xu H: HMGB1 modulates Lewis cell autophagy and promotes cell survival via RAGE-HMGB1-Erk1/2 positive feedback during nutrient depletion. Immunobiology 2015, 220(5): 539-544.

- Chen R, Kang R, Tang D: The mechanism of HMGB1 secretion and release. Exp Mol Med 2022, 54(2): 91-102.

- Tang Y, Zhao X, Antoine D, Xiao X, Wang H, Andersson U, Billiar TR, Tracey KJ, Lu B: Regulation of Posttranslational Modifications of HMGB1 During Immune Responses. Antioxid Redox Signal 2016, 24(12): 620-634.

- Yang H, Lundbäck P, Ottosson L, Erlandsson-Harris H, Venereau E, Bianchi ME, Al-Abed Y, Andersson U, Tracey KJ: Redox modifications of cysteine residues regulate the cytokine activity of HMGB1. Mol Med 2021, 27(1): 58.

- Schiraldi M, Raucci A, Muñoz LM, Livoti E, Celona B, Venereau E, Apuzzo T, De Marchis F, Pedotti M, Bachi A et al: HMGB1 promotes recruitment of inflammatory cells to damaged tissues by forming a complex with CXCL12 and signaling via CXCR4. J Exp Med 2012, 209(3): 551-563.

- Yang H, Lundbäck P, Ottosson L, Erlandsson-Harris H, Venereau E, Bianchi ME, Al-Abed Y, Andersson U, Tracey KJ, Antoine DJ: Redox modification of cysteine residues regulates the cytokine activity of high mobility group box-1 (HMGB1). Mol Med 2012, 18(1): 250-259.

- Venereau E, Casalgrandi M, Schiraldi M, Antoine DJ, Cattaneo A, De Marchis F, Liu J, Antonelli A, Preti A, Raeli L et al: Mutually exclusive redox forms of HMGB1 promote cell recruitment or proinflammatory cytokine release. J Exp Med 2012, 209(9): 1519-1528.

- Janko C, Filipović M, Munoz LE, Schorn C, Schett G, Ivanović-Burmazović I, Herrmann M: Redox modulation of HMGB1-related signaling. Antioxid Redox Signal 2014, 20(7): 1075-1085.

- Lange SS, Vasquez KM: HMGB1: the jack-of-all-trades protein is a master DNA repair mechanic. Mol Carcinog 2009, 48(7): 571-580.

- Kang R, Chen R, Zhang Q, Hou W, Wu S, Cao L, Huang J, Yu Y, Fan XG, Yan Z et al: HMGB1 in health and disease. Mol Aspects Med 2014, 40: 1-116.

- El Gazzar M, Yoza BK, Chen X, Garcia BA, Young NL, McCall CE: Chromatin-specific remodeling by HMGB1 and linker histone H1 silences proinflammatory genes during endotoxin tolerance. Mol Cell Biol 2009, 29(7): 1959-1971.

- Morrison AJ, Shen X: Chromatin remodelling beyond transcription: the INO80 and SWR1 complexes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2009, 10(6): 373-384.

- Dai Y, Wong B, Yen YM, Oettinger MA, Kwon J, Johnson RC: Determinants of HMGB proteins required to promote RAG1/2-recombination signal sequence complex assembly and catalysis during V(D)J recombination. Mol Cell Biol 2005, 25(11): 4413-4425.

- Voong CK, Goodrich JA, Kugel JF: Interactions of HMGB Proteins with the Genome and the Impact on Disease. Biomolecules 2021, 11(10): 1451.

- Kang R, Zhang Q, Zeh HJ, 3rd, Lotze MT, Tang D: HMGB1 in cancer: good, bad, or both? Clin Cancer Res 2013, 19(15): 4046-4057.

- Stros M, Bacíková A, Polanská E, Stokrová J, Strauss F: HMGB1 interacts with human topoisomerase IIalpha and stimulates its catalytic activity. Nucleic Acids Res 2007, 35(15): 5001-5013.

- Livesey KM, Kang R, Vernon P, Buchser W, Loughran P, Watkins SC, Zhang L, Manfredi JJ, Zeh HJ, 3rd, Li L et al: p53/HMGB1 complexes regulate autophagy and apoptosis. Cancer Res 2012, 72(8): 1996-2005.

- Bihr S, Ohashi R, Moore AL, Rüschoff JH, Beisel C, Hermanns T, Mischo A, Corrò C, Beyer J, Beerenwinkel N et al: Expression and Mutation Patterns of PBRM1, BAP1 and SETD2 Mirror Specific Evolutionary Subtypes in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Neoplasia 2019, 21(2): 247-256.

- Martinotti S, Patrone M, Ranzato E: Emerging roles for HMGB1 protein in immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Immunotargets Ther 2015, 4: 101-109.

- Datta S, Rahman MA, Koka S, Boini KM: High Mobility Group Box 1 (HMGB1): Molecular Signaling and Potential Therapeutic Strategies. Cells 2024, 13(23): 1946.

- Yang H, Antoine DJ, Andersson U, Tracey KJ: The many faces of HMGB1: molecular structure-functional activity in inflammation, apoptosis, and chemotaxis. J Leukoc Biol 2013, 93(6): 865-873.

- Alhasan BA, Margulis BA, Guzhova IV: HMGB1: A Central Node in Cancer Therapy Resistance. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26(24): 12010.

- Li D, Lei X, Zhao L, Fu Q, Chen Y, Yang X: Mechanism of action of HMGB1 in urologic malignancies. Front Oncol 2025, 15: 1593157.

- Pirani E, Paparoditis P, Pecoraro M, Danelon G, Thelen M, Cecchinato V, Uguccioni M: Tumor cells express and maintain HMGB1 in the reduced isoform to enhance CXCR4-mediated migration. Front Immunol 2024, 15: 1358800.

- Li G, Liang X, Lotze MT: HMGB1: The Central Cytokine for All Lymphoid Cells. Front Immunol 2013, 4: 68.

- Srinivasan M, Banerjee S, Palmer A, Zheng G, Chen A, Bosland MC, Kajdacsy-Balla A, Kalyanasundaram R, Munirathinam G: HMGB1 in hormone-related cancer: a potential therapeutic target. Horm Cancer 2014, 5(3): 127-139.

- Xiao K, Liu C, Tu Z, Xu Q, Chen S, Zhang Y, Wang X, Zhang J, Hu CA, Liu Y: Activation of the NF-κB and MAPK Signaling Pathways Contributes to the Inflammatory Responses, but Not Cell Injury, in IPEC-1 Cells Challenged with Hydrogen Peroxide. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2020, 2020: 5803639.

- Liu F, Li X, Zhang Y, Ge S, Shi Z, Liu Q, Jiang S: Targeting tumor-associated macrophages to overcome immune checkpoint inhibitor resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2025, 44(1): 227.

- Shao LH, Zhu L, Wang M, Ning Y, Chen FQ, Gao XQ, Yang CT, Wang HW, Li HL: Mechanisms involved in the HMGB1 modulation of tumor multidrug resistance (Review). Int J Mol Med 2023, 52(2): 69.

- Parker KH, Sinha P, Horn LA, Clements VK, Yang H, Li J, Tracey KJ, Ostrand-Rosenberg S: HMGB1 enhances immune suppression by facilitating the differentiation and suppressive activity of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Res 2014, 74(20): 5723-5733.

- Chung H, Nam H, Nguyen-Phuong T, Jang J, Hong SJ, Choi SW, Park SB, Park CG: The blockade of cytoplasmic HMGB1 modulates the autophagy/apoptosis checkpoint in stressed islet beta cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2021, 534: 1053-1058.

- Xu T, Jiang L, Wang Z: The progression of HMGB1-induced autophagy in cancer biology. Onco Targets Ther 2019, 12: 365-377.

- Liu L, Yang M, Kang R, Wang Z, Zhao Y, Yu Y, Xie M, Yin X, Livesey KM, Lotze MT et al: HMGB1-induced autophagy promotes chemotherapy resistance in leukemia cells. Leukemia 2011, 25(1): 23-31.

- Chen Y, Lin C, Liu Y, Jiang Y: HMGB1 promotes HCC progression partly by downregulating p21 via ERK/c-Myc pathway and upregulating MMP-2. Tumour Biol 2016, 37(4): 4399-4408.

- Idoudi S, Bedhiafi T, Pedersen S, Elahtem M, Alremawi I, Akhtar S, Dermime S, Merhi M, Uddin S: Role of HMGB1 and its associated signaling pathways in human malignancies. Cell Signal 2023, 112: 110904.

- Maharjan S, Oku M, Tsuda M, Hoseki J, Sakai Y: Mitochondrial impairment triggers cytosolic oxidative stress and cell death following proteasome inhibition. Sci Rep 2014, 4: 5896.

- Chen R, Zou J, Zhong X, Li J, Kang R, Tang D: HMGB1 in the interplay between autophagy and apoptosis in cancer. Cancer Lett 2024, 581: 216494.

- De-Giorgio F, Bergamin E, Baldi A, Gatta R, Pascali VL: Immunohistochemical expression of HMGB1 and related proteins in the skin as a possible tool for determining post-mortem interval: a preclinical study. Forensic Sci Med Pathol 2024, 20(1): 149-165.

- Kwak MS, Kim HS, Lee B, Kim YH, Son M, Shin JS: Immunological Significance of HMGB1 Post-Translational Modification and Redox Biology. Front Immunol 2020, 11: 1189.

- Fan A, Gao M, Tang X, Jiao M, Wang C, Wei Y, Gong Q, Zhong J: HMGB1/RAGE axis in tumor development: unraveling its significance. Front Oncol 2024, 14: 1336191.

- Chen H, Lin X, Liu H, Huang C, Li R, Ai J, Wei J, Xiao S: HMGB1 Translocation is Associated with Tumor-Associated Myeloid Cells and Involved in the Progression of Fibroblastic Sarcoma. Pathol Oncol Res 2021, 27: 608582.

- Wu CZ, Zheng JJ, Bai YH, Xia P, Zhang HC, Guo Y: HMGB1/RAGE axis mediates the apoptosis, invasion, autophagy, and angiogenesis of the renal cell carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther 2018, 11: 4501-4510.

- Wang S, Zhang Y: HMGB1 in inflammation and cancer. J Hematol Oncol 2020, 13(1): 116.

- Zeng W, Zhang X, Jiang Y, Luo Y, Wang Z, Du X, Chen L: Dualistic Roles of High Mobility Group Box 1 in Cancer and Inflammation. Cancer Med 2025, 14(23): e71455.

- Kam NW, Wu KC, Dai W, Wang Y, Yan LYC, Shakya R, Khanna R, Qin Y, Law S, Lo AWI et al: Peritumoral B cells drive proangiogenic responses in HMGB1-enriched esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Angiogenesis 2022, 25(2): 181-203.

- Kwak MS, Han M, Lee YJ, Choi S, Kim J, Park IH, Shin JS: ROS anchor PAMPs-mediated extracellular HMGB1 self-association and its dimerization enhances pro-inflammatory signaling. Redox Biol 2025, 80: 103521.

- Wang M, Gauthier A, Daley L, Dial K, Wu J, Woo J, Lin M, Ashby C, Mantell LL: The Role of HMGB1, a Nuclear Damage-Associated Molecular Pattern Molecule, in the Pathogenesis of Lung Diseases. Antioxid Redox Signal 2019, 31(13): 954-993.

- Chen R, Zou J, Kang R, Tang D: The redox protein HMGB1 in cell death and cancer. Antioxid Redox Signal 2023, Epub ahead of print.

- I T, Kanai R, Seki M, Agata H, Kagami H, Murata H, Asahina I, Tran SD, Sumita Y: Inhibition of the TLR4/RAGE pathway by clearance of extracellular HMGB1 is a potential therapeutic target for radiation-damaged salivary glands. Regen Ther 2025, 30: 476-490.

- Xue J, Suarez JS, Minaai M, Li S, Gaudino G, Pass HI, Carbone M, Yang H: HMGB1 as a therapeutic target in disease. J Cell Physiol 2021, 236(5): 3406-3419.

- Shahzad A, Ni Y, Teng Z, Liu W, Bai H, Sun Y, Cui K, Duan Q, Liu X, Xu Z et al: Neutrophil extracellular traps and metabolic reprogramming in renal cell carcinoma: implications for tumor progression and immune-based therapeutics. Cancer Biol Med 2025, 22(11): 1282-1303.

- Funaishi K, Yamaguchi K, Tanahashi H, Kurose K, Sakamoto S, Horimasu Y, Masuda T, Nakashima T, Iwamoto H, Hamada H et al: HMGB1 assists the predictive value of tumor PD-L1 expression for the efficacy of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibody in NSCLC. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2025, 95(1): 28.

Annals of urologic oncology

p-ISSN: 2617-7765, e-ISSN: 2617-7773

Copyright © Ann Urol Oncol. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License.

Copyright © Ann Urol Oncol. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License.

Submit Manuscript

Submit Manuscript