Review Article | Open Access

Epigenetic Alterations and Chromatin Landscape Remodeling in Urothelial Bladder Cancer: Molecular Drivers, Biomarker Potential, and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies

Amr Abd-Elraheem Abdo1, Ahmed Mohamed Kamel11College of Biotechnology, Misr University for Science and Technology (MUST), 6th of October City, Giza 12566, Egypt.

Correspondence: Amr Abd-Elraheem Abdo (College of Biotechnology, Misr University for Science and Technology (MUST), 6th of October City, Giza 12566, Egypt; Email: amrabdulraheem675@gmail.com).

Annals of Urologic Oncology 2025, 8(4): 211-221. https://doi.org/10.32948/auo.2025.12.03

Received: 22 Oct 2025 | Accepted: 28 Nov 2025 | Published online: 10 Dec 2025

Key words urothelial bladder cancer, epigenetics, chromatin remodeling, DNA methylation, histone post-translational modification

Traditionally, the pathogenesis of UBC has been attributed mainly to classical genetic modifications such as activating mutations in FGFR3, PIK3CA and HRAS or loss-of-function mutations in tumor suppressors like TP53, RB1 and PTEN [3, 4]. Although such genetic alterations initiate and promote tumorigenesis, they do not fully explain the clinical heterogeneity among patients. Accumulating evidence is revealing that epigenetic deregulation plays a central role in determining UBC biology, including gene expression control, chromatin architecture regulation, transcriptional program control and metabolism adaptation, and tumor–immune interactions [5]. These epigenetic changes become especially relevant for tumor plasticity, intratumoral heterogeneity, treatment resistance, and relapse that still constitute important drawbacks in clinics [6].

Encompassing epigenetic regulation includes modifications that are inheritable but do not involve changes to the nucleotide sequence. The principal mechanisms involve DNA methylation, histone modifications (e.g. acetylation, methylation and ubiquitination), chromatin remodelling and enhancer–promoter looping [7]. In UBC, these processes are often dysregulated by chromatin regulating mutations such as ARID1A, KMT2C/D, EP300 and CREBBP or abnormal functions of epigenetic enzymes including EZH2, DNMTs and HDACs [8]. These changes collaborate with genetic abnormalities to reshape chromatin architecture into permissive or repressive transcriptional landscapes, which affect the ability of tumor cells to escape growth suppression, survive genotoxic stress and acclimate to the tumor microenvironment [8].

A signature feature of UBC is the rewiring of enhancer and super-enhancer networks promoting oncogenic transcriptional programs that sustain aspects of proliferation, invasion, and metastases [9]. Defects in chromatin-modifying enzymes in concert with metabolic reprogramming and hypoxia signaling hijack these regulatory regions to enhance the activity of known potent oncogenes such as MYC, FGFR3 and angiogenic factors. This enhancer reprogramming results in enhanced aggressive tumor phenotypes that drives therapeutic resistance through maintenance of transcriptional plasticity and cellular heterogeneity [10].

Additionally, epigenetic changes are relevant for tumor–immune crosstalk. Impaired antigen presentation, cytokine signaling, and interferon responses by dysregulated chromatin accessibility and histone modifications can shape an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment [11, 12]. For instance, ARID1A or KDM6A loss is associated with impaired MHC class I expression, and EZH2 overactivity drives T-cell exclusion and inflammatory gene suppression [13]. A knowledge of these epigenetic mechanisms leads to the rational combining of epigenetic modulators with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) to increase antitumor immunity in certain patient subsets [14].

The reversibility of epigenetic modifications renders them as ideal therapeutic targets. Agents including EZH2 inhibitors, HDAC inhibitors, BET inhibitors and DNMT inhibtiors are being studied in UBC as single agent or combined with immune therapy, targeted therapy or chemotherapy [15, 16]. Furthermore, epigenetic tumor and non-invasive markers such as circulating tumor DNA and urine can be used to early detection, disease monitoring as well as patient stratification [17]. By integrating epigenomic characterization of UBC with genome-wide maps of genomic, transcriptomic and proteomic features, the scope of classification of UBC into biologically and clinically relevant subtypes to enable precision oncology becomes apparent [18].

However, there are a number of requirements and challenges to address. Intratumoral heterogeneity in UBC makes it difficult to establish strong biomarkers and treatment regimens. Epigenetic changes are frequently dynamic and context-specific, with function determined by co-option with the tumour microenvironment (TME), hypoxia, and metabolic programming [19, 20]. Further, off-target activities and the reversible nature of many epigenetic marks represent challenges to achieving efficient and permanent treatments. Tackling these challenges calls for mechanistic and systems level studies, high resolution epigenomic mapping, and translational investigations integrating molecular biology with the clinical dimension.

The objective of this review is to fine-tune the current knowledge on epigenetic reprogramming in UBC. We analyse chromatin-remodelling, histone-modifying and DNA-methylation mechanisms, and explore how they dynamically interact to establish tumour transcriptional outputs, enhancer landscapes and immune-immunomankinductive processes. We also address major regulators of chromatin, their contribution to the definition of molecular subtypes, as well as translational implications for biomarker discovery and therapeutic intervention. Last, we spotlight frontier technologies including single-cell and spatial epigenomics as well as AI-powered multi-omics integration, which are revolutionizing research and precision medicine in UBC. Through unifying the concepts of mechanisms and clinic, this review focuses to direct future research, therapeutic design and stratification in patients suffering from urothelial bladder cancer.

Chromatin remodeling abnormalities

Chromatin Remodelers (SWI/SNF [ARID1A, SMARCA4] and NuRD [CHD4]) chromatin remodeling complexes that play a central role in the regulation of nucleosome positions and DNA accessibility to transcription factors [24]. In UBC, mutations in ARID1A, which are found in about 20%–25% of MIBCs, alter chromatin structure and loosen transcriptional fidelity along with aberrant regulation of pathways that mediate DNA damage response, cell cycle checkpoint control and apoptosis [13]. Biologically, depletion of ARID1A has been associated with tumor cell plasticity and an immunosuppressive immune microenvironment, as well as chemotherapy resistance, underscoring its role in both tumorigenesis and treatment response [13, 25].

Mutation of H3K4 methyltransferases KMT2C and KMT2D, which mediate enhancer-associated chromatin accessibility and function, are also seen [26, 27]. These changes contribute to pathological activation of oncogenic transcriptional programs, such as those controlling proliferation, invasion and angiogenesis [28]. Perturbation of these enhancer landscapes by mutations in chromatin remodelers is also a strong driver of intratumoral heterogeneity, leading to the generation of subclones with different transcriptional and metabolic properties that can have varying therapeutic responses, including immune checkpoint inhibitors [29].

Beside mutations, defective function of chromatin remodelers can be caused by aberrant post-translational modifications or altered associated cofactors [30]. For instance, uncontrolled recruitment of SWI/SNF complexes to enhancers or promoters can enhance oncogenic signals or repress tumor suppressor genes in a manner that is mutation independent [31]. Collectively, these mechanisms of action support the importance of chromatin remodeling in UBC pathogenesis and identify it as a promising target for epigenetic therapy to re-establish appropriate chromatin accessibility and transcriptional regulation.

Histone modification dysregulation

Modifications of histones such as methylation, acetylation and ubiquitination are important for chromatin structure maintenance and gene expression regulation [32]. In UBC, histone-modifying enzyme alterations are frequent and induce transcriptional reprogramming. Both acquired and germline loss-of-function mutations in EP300 and CREBBP, two master histone acetyltransferases (HATs), lead to decreased promoter and enhancer histone acetylation of tumor suppressor genes, compromising transcriptional activation [24, 26]. This epigenetic silencing promotes unhindered proliferation, evasion of apoptosis, and increased survival against tumor killing leading to progression and resistance of the disease. Elevated levels or gain-of-function mutations in the catalytic subunit of PRC2, EZH2, has been shown to induce H3K27 trimethyl (H3K27me3) and silence expression of differentiation and immune response genes [33]. EZH2-induced silencing plays a role in promoting a dedifferentiated tumor phenotype and enabling evasion of the immune system via suppression of chemokines and tools for antigen presentation [34]. Concomitantly, mutations in histone demethylases such as KDM6A compromise H3K27me3 erasure at enhancers, thus additionally increasing transcriptional flexibility and oncogenic signaling [32].

Histone modifications do not function alone and work together with chromatin remodelers and DNA methylation to sculpt enhancer landscapes and affect TF binding [24]. The combination patterns of histone acetylation and methylation are super-enhancer features determining the expression levels of or key oncogenes HIV-1 Tat and Angiogenin [35]. Aberrant regulation of these marks predisposes to EMT (epithelial-mesenchymal transition), angiogenesis, and resistance to both chemotherapy and immunotherapy [36]. It is of note that a great impetus exists for the pharmacologic inhibition of histone-modifying enzymes with the aim to reestablish normal transcriptional programs and enhance tumor susceptibility to conventional antineoplastic agents [37].

DNA methylation deregulation

DNA methylation, the modification of cytosine residue by adding a methyl group in CpG dinucleotides, was a vital epigenetic mechanism in controlling gene expression in UBC [16]. Histone modification and promoter aberrant hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes like CDKN2A and RASSF1A contributes to transcriptional silencing, eventually inducing the dysregulation of cell cycle control with apoptosis resistance or tumor proliferation [38]. Hypermethylated regions are commonly over-represented in networks regulating DNA repair, cell adhesion and immune surveillance, which can lead to a more aggressive tumour phenotype with enhanced metastatic capacity [39]. In contrast, loss of global DNA methylation induces chromosome instability and activation of proto-oncogenic pathways involved in proliferation, angiogenesis and metabolic adaptation [40]. Hypomethylation can also lead to the reexpression of transposable elements and endogeneous retroviral sequences, which could mediate genomic instability or immune evasion [41]. These alterations often crosstalk with histone modification and chromatin remodeling to affect enhancer accessibility, as well as TF binding, thereby serving to promote the oncogenic transcriptional program [24]. Notably, DNA methylation is being explored as a non-invasive biomarker for UBC [42]. As urine or plasma are easy to collect, detection of the methylated DNA fragments would facilitate early diagnosis and monitoring recurrence of disease as well as follow-up after treatment [17]. Methylation-based tests may support other diagnostic tools, lead to better patient stratification and tailor patients' treatment in a more individualised manner [43]. In total, DNA methylation dysregulation is a major cause of transcriptional plasticity and a worthy direction for translational studies in UBC (Table 1) [44].

|

Table 1. Key chromatin and epigenetic regulators in urothelial bladder cancer. |

||||

|

Gene |

Mutation frequency |

Epigenetic function |

Impact on tumor biology |

Therapeutic implication |

|

ARID1A |

20-25% |

SWI/SNF chromatin remodeler; regulates nucleosome positioning |

Alters chromatin accessibility, transcriptional programs, DNA damage response; promotes immune evasion |

Potential target for chromatin-directed therapies; may influence immunotherapy response |

|

KMT2C/D |

15-20% |

Histone methyltransferases (H3K4) affecting enhancer landscapes |

Aberrant enhancer activation; promotes oncogenic transcriptional programs and tumor plasticity |

Investigational enhancer-targeted therapies; combination with BET or HDAC inhibitors |

|

EP300 |

10-15% |

Histone acetyltransferase; regulates transcriptional activation |

Loss impairs tumor suppressor gene expression; contributes to therapy resistance |

HDAC or BET inhibitor combinations may restore transcriptional control |

|

CREBBP |

5-10% |

Histone acetyltransferase; modulates chromatin accessibility |

Disruption leads to transcriptional dysregulation and enhanced proliferation |

Combination with epigenetic modulators or immunotherapy |

|

EZH2 |

10-15% (overexpression) |

Histone methyltransferase (H3K27); mediates gene repression |

Silences differentiation and immune genes; promotes proliferation and immune evasion |

EZH2 inhibitors; synergistic with immunotherapy and chemotherapy |

|

KDM6A |

20-25% |

Histone demethylase (H3K27); regulates enhancer activity |

Alters transcriptional plasticity; facilitates tumor progression and immune escape |

Potential target for combination epigenetic therapy |

|

ARID1A: AT-Rich interaction domain 1A; KMT2C/D: lysine methyltransferase 2C/2D; EP300: E1A binding protein P300; CREBBP: CREB binding protein; EZH2: enhancer of zeste homolog 2; KDM6A: lysine demethylase 6A; SWI/SNF: SWItch/sucrose non-fermentable (chromatin remodeling complex); HDACs: histone deacetylases. |

||||

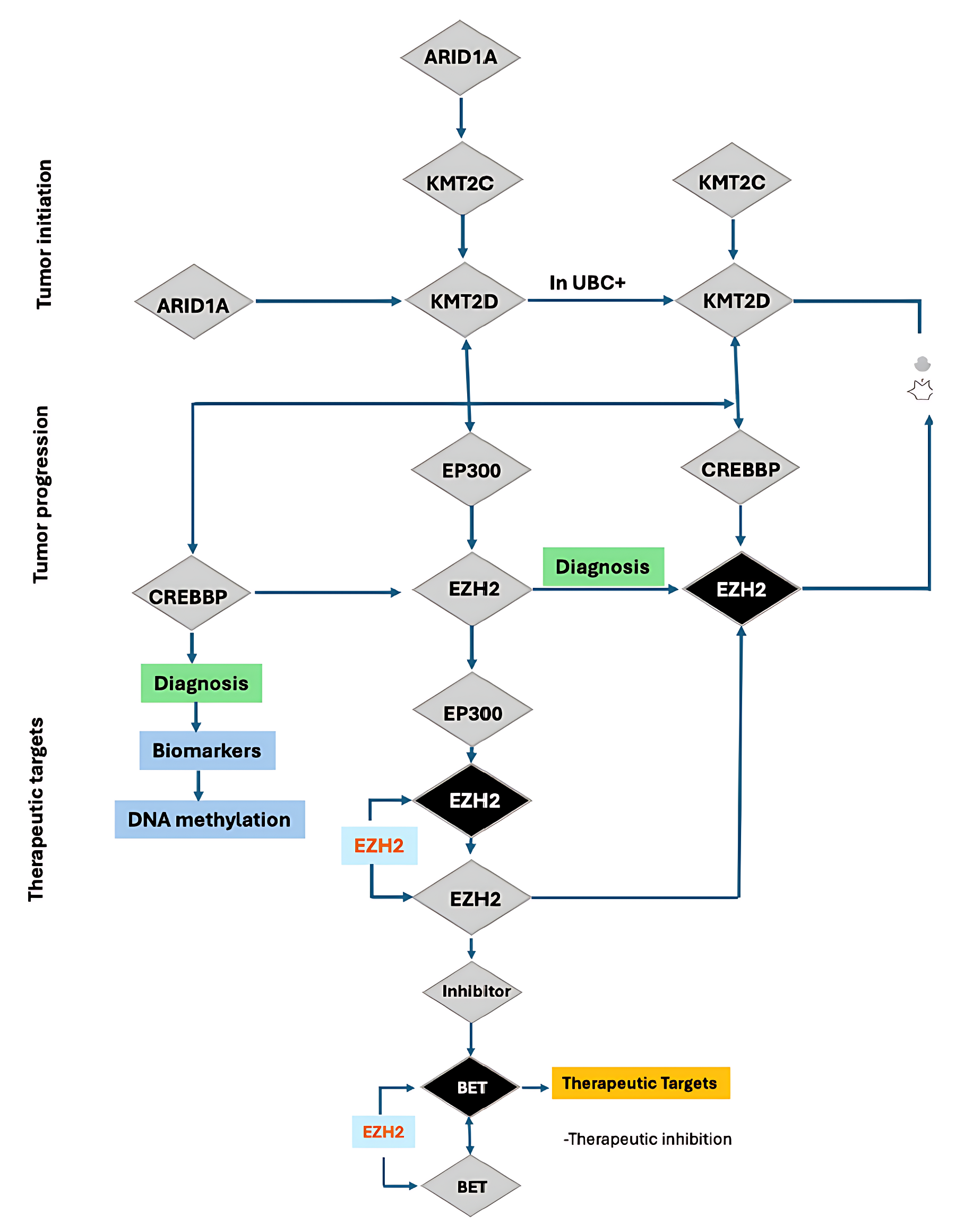

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of tumor initiation, progression, and therapeutic targeting involving chromatin-modifying genes in urothelial bladder cancer (UBC). This schematic outlines the stepwise genetic modification and epigenetic deregulation in the induction of tumorigenesis. Early in tumorigenesis, ARID1A inactivation results in loss of function alteration downregulating KMT2C and KMT2D which are master regulators of histone methylation. In UBC+, KMT2C/KMT2D changes contribute to EP300 (histone acetyltransferase p300) and CREBBP- (CREB-binding protein) pathways in the context of an epigenetic rewiring that fosters tumor evolution. Progressive dysregulation increases the activity or expression of the catalytic subunit of the PRC2 (Polycomb Repressive Complex 2) EZH2 (enhancer of zeste homolog 2), which mediates trimethylation of histone H3K27. EZH2 overexpression is considered a key event associated with diagnostic biomarkers and DNA methylation alterations. Treatment modalities are directed towards abnormal epigenome modifiers. EZH2 inhibitors and subsequent inhibition of BET proteins (bromodomain and extra-terminal domain proteins) are highlighted as prospective therapeutic strategies, mainly because of their involvement in gene regulation and dependency mechanisms in EZH2-mediated cancers. The screen depicts a hierarchy of genetic mutations to epigenetically driven therapeutic targets, with decision points for diagnostic and therapy intervention.

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of tumor initiation, progression, and therapeutic targeting involving chromatin-modifying genes in urothelial bladder cancer (UBC). This schematic outlines the stepwise genetic modification and epigenetic deregulation in the induction of tumorigenesis. Early in tumorigenesis, ARID1A inactivation results in loss of function alteration downregulating KMT2C and KMT2D which are master regulators of histone methylation. In UBC+, KMT2C/KMT2D changes contribute to EP300 (histone acetyltransferase p300) and CREBBP- (CREB-binding protein) pathways in the context of an epigenetic rewiring that fosters tumor evolution. Progressive dysregulation increases the activity or expression of the catalytic subunit of the PRC2 (Polycomb Repressive Complex 2) EZH2 (enhancer of zeste homolog 2), which mediates trimethylation of histone H3K27. EZH2 overexpression is considered a key event associated with diagnostic biomarkers and DNA methylation alterations. Treatment modalities are directed towards abnormal epigenome modifiers. EZH2 inhibitors and subsequent inhibition of BET proteins (bromodomain and extra-terminal domain proteins) are highlighted as prospective therapeutic strategies, mainly because of their involvement in gene regulation and dependency mechanisms in EZH2-mediated cancers. The screen depicts a hierarchy of genetic mutations to epigenetically driven therapeutic targets, with decision points for diagnostic and therapy intervention.

Figure 2. Chromatin remodeling abnormalities and downstream epigenetic dysregulation contributing to tumorigenesis. This diagram shows how malfunctioning chromatin-remodeling complexes cause histone-modification defects, a failure in DNA methylation. Mutation of the SWI/SNF complex—ARID1A (AT-rich interaction domain 1A) and SMARCA4 (SWI/SNF-related, matrix-associated, actin-dependent regulator of chromatin subfamily A member 4) are most frequently involved—results in a defect in nucleosomal repositioning. Simultaneous NuRD complex abnormalities involving CHD4 (chromodomain-helicase-DNA-binding protein 4) lead to reduction of chromatin accessibility. These remodeling deficiencies lead to deregulation of global histone modifications. Somatic mutations of the histone H3K27 methylase, EZH2 (enhancer of zeste homolog 2), also results in a loss of the repressive H3K27 trimethylation. Concomitantly, additional chromatin-regulatory machineries target the key epigenetic co-activator EP300 (histone acetyltransferase p300). Deletion or defect of EP300 or its paralogue CREBBP (CREB-binding protein) disrupts histone acetylation equilibrium and induces epigenetic silencing. These upstream chromatin alterations converge on DNA methylation, with genes becoming hypermethylated and silenced. Shown here are examples of CDKN2A, cellk-cycle control regulator, and RASSF1A, tumor-suppressor gene that is often inactivated by promoter hypermethylation. The diagram represents the cascade of events from chromatin-remodelling defect to epigenetic silencing in oncogenic transformation.

Figure 2. Chromatin remodeling abnormalities and downstream epigenetic dysregulation contributing to tumorigenesis. This diagram shows how malfunctioning chromatin-remodeling complexes cause histone-modification defects, a failure in DNA methylation. Mutation of the SWI/SNF complex—ARID1A (AT-rich interaction domain 1A) and SMARCA4 (SWI/SNF-related, matrix-associated, actin-dependent regulator of chromatin subfamily A member 4) are most frequently involved—results in a defect in nucleosomal repositioning. Simultaneous NuRD complex abnormalities involving CHD4 (chromodomain-helicase-DNA-binding protein 4) lead to reduction of chromatin accessibility. These remodeling deficiencies lead to deregulation of global histone modifications. Somatic mutations of the histone H3K27 methylase, EZH2 (enhancer of zeste homolog 2), also results in a loss of the repressive H3K27 trimethylation. Concomitantly, additional chromatin-regulatory machineries target the key epigenetic co-activator EP300 (histone acetyltransferase p300). Deletion or defect of EP300 or its paralogue CREBBP (CREB-binding protein) disrupts histone acetylation equilibrium and induces epigenetic silencing. These upstream chromatin alterations converge on DNA methylation, with genes becoming hypermethylated and silenced. Shown here are examples of CDKN2A, cellk-cycle control regulator, and RASSF1A, tumor-suppressor gene that is often inactivated by promoter hypermethylation. The diagram represents the cascade of events from chromatin-remodelling defect to epigenetic silencing in oncogenic transformation.

HDAC inhibitors change histone acetylation pattern in order to restore transcription of tumor supressor genes and their accessiblity to chromatin [16]. This form of epigenetic reprogramming could also potentiate the effectivity of classic therapy (chemotherapy, immune checkpoint inhibitor) [32]. Preclinical and early-phase clinical translation studies demonstrate a potential synergy between HDAC inhibition and other epigenetic modalities or immunotherapy, supporting rational combination strategies [55]. BET inhibitors disrupt super-enhancer–driven transcriptional programs, including oncogenes such as MYC and FGFR3, which are essential for tumour growth and survival [56]. Deconstruction of enhancer-mediated transcriptional addiction, BET inhibition, and tumor growth BET inhibition by super-enhancers disrupts tumor growth and transcriptional plasticity [57]. These agents are under preclinical or early clinical investigation in association with HDAC inhibitors or even therapeutic vaccines aiming to potentiate antitumor responses.

DNMT inhibitors can reverse promoter hypermethylation thereby reactivating expression of tumor suppressor and immune-regulatory genes. This reactivation in turns increases immunogenicity of the tumors and sensitizes them to checkpoint blockade, raising the possibility of combining DNMT inhibitors with immunotherapeutic approaches [38, 58]. Early-phase trials are investigating their use in combination with chemotherapy or immune checkpoint inhibitors. Prospective drugs that can target chromatin remodelers (e.g., SWI/SNF) and enhancer regulators (e.g., KMT2D/C) toward restoring the chromatin accessibility and enhancing dysregulation [59]. These are still in the pre-clinical phase but combined with EZH2 or HDAC inhibitors (HDACI) could offer synthetic lethality and therefore represent a mechanism for future combination strategies [60].

In summary, rational combinations based on insight into chromatin dynamics and enhancer reprogramming and immune modulation are becoming a centerpiece of precision epigenetic therapy in UBC. Table 2 provides an overview on the main targets and classes of drugs, their mechanism of action, therapeutic stage (clinical phase) and potential combination therapies that can be considered as quick-reference for present and prospective drug development.

|

Table 2. Epigenetic therapeutic strategies in urothelial bladder cancer. |

||||

|

Target |

Drug class |

Mechanism of action |

Clinical status |

Combination approaches |

|

EZH2 |

EZH2 inhibitor |

Reverses H3K27me3-mediated gene repression; restores differentiation and immune gene expression |

Phase I/II trials |

With immune checkpoint inhibitors or chemotherapy |

|

HDACs |

HDAC inhibitor |

Modulates histone acetylation, restores tumor suppressor gene expression |

Phase I/II trials |

With immune checkpoint inhibitors or chemotherapy |

|

BET proteins |

BET inhibitor |

Blocks super-enhancer–driven oncogene transcription (e.g., MYC, FGFR3) |

Preclinical/early clinical |

With HDAC inhibitors or immunotherapy |

|

DNMTs |

DNMT inhibitor |

Reverses promoter hypermethylation, enhancing tumor immunogenicity |

Preclinical/early clinical |

With checkpoint inhibitors or chemotherapy |

|

SWI/SNF |

Chromatin remodeler-targeted agents (investigational) |

Restores chromatin accessibility and enhancer function |

Preclinical |

Combination with EZH2 or HDAC inhibitors |

|

KMT2C/D |

Epigenetic modulators (investigational) |

Corrects enhancer dysregulation, reduces oncogenic transcription |

Preclinical |

With BET or HDAC inhibitors |

|

EZH2: enhancer of zeste homolog 2; HDACs: histone deacetylases; BET: bromodomain and extra-terminal domain proteins; DNMTs: DNA methyltransferases; SWI/SNF: SWItch/sucrose non-fermentable (chromatin remodeling complex); KMT2C/D: lysine methyltransferase 2C/2D. |

||||

The combination of these epigenetic biomarkers with genomic, transcriptomic and proteomic information improves the predictive accuracy and it sustains precision oncology. Multimodal analyses should help to find patient subclasses that could benefit from distinct therapeutic strategies, such as targeted epigenetic therapies or rational combinations of drugs [68, 69]. For example, a combination of epigenetic modulators and immune checkpoint inhibitors could boost antitumor immune responses in tumors with suppressive chromatin landscapes, whereas methylation-based monitoring might facilitate dose normalization or timely treatment change [70]. Finally, application of these UBC‐related insights to clinical practice could lead to the development of increasingly individualized and mechanism‐based treatments that take advantage of UBC's distinct Achilles' heels [71].

Design of highly selective inhibitors against chromatin remodelers and histone-modifying enzymes remains an urgent need. Such highly selective inhibitors with few offtarget effects should increase the therapeutic index [5, 30]. In parallel, rational combination strategies coupling epigenetic modulators with immunotherapy, targeted therapy or chemotherapy should be optimized in order to defeat tumor plasticity and resistance [73]. Temporal tracking of epigenetic transitions during treatment is also important, because dynamic epigenomic alterations can inform on adaptive resistance mechanisms and novel vulnerabilities [73, 74].

Synthetic lethality strategies offer an attractive option for adding chromatin or epigenetic vulnerabilities with other targeted agents to result in specific tumor cell death [32]. Nevertheless, significant obstacles persist, such as intratumoral heterogeneity, the dynamic nature of epigenetic marks and off-target effects of epigenetic therapeutics. To overcome these challenges, we need advanced preclinical models, single-cell and spatial epigenomic profiling, and multi-omics integration. To unlock the full potential of epigenetic dependencies and enable mechanistic observations to be translated into better clinical results for patients with UBC, these barriers must be addressed.

The increasing recognition of epigenetic deregulation in UBC has established the foundation for translation of chromatin- and histone-based markers into the clinics. Mutations in chromatin-remodeling genes, such as ARID1A and KMT2C/KMT2D, or histone-modifying enzymes (e.g., EP300/CREBBP/EZH2) are associated with unique prognostic and therapeutic phenotypes. For instance, ARID1A-deficient tumors have frequently defective DNA damage response and immune infiltration, therefore may be sensitive to the combination of epigenetic-immunotherapy whereas EZH2-overexpressed tumors are correlated with a high-risk phenotype and are also possible candidates for preferential sensitivity to EZH2 inhibition. In addition to gene mutations, epigenetic characteristics such as chromatin accessibility, histone modification profile and DNA methylation status serve as independent biomarkers for the stratification of patients. Notably, urine- or plasma-based DNA meUrothelial bladder cancer (UBC) is a molecular and clinically heterogeneous disease in which epigenetic alterations have been proven critical for tumor behavior, progression and response to therapy. Abnormalities in chromatin remodeling, imbalances in histone modifications, and changes in DNA methylation all contribute to reprogramming of transcriptional programs, enhancer landscapes and tumor–immune interactions leading to intratumoral heterogeneity, immune escape and resistance to therapy. Somatic mutations, especially those in major epigenetic regulators such as ARID1A, KMT2C, KMT2D, EP300, CREBBP and EZH2 play both mechanistic roles but also present promising biomarkers for patient stratification and prognosis evaluation and potential targeted therapy.

The epigenetic changes are reversible, which provides special opportunities for therapy. Pharmacologic inhibition of EZH2, HDACs, BET proteins, DNMTs and selected chromatin remodelers, as monoagents or in combination with immunotherapy, chemotherapy or targeted therapy hold promise to reactivate TS gene expression, control enhancer function and to sensitize tumors to killing by immunity. Recent advances in single-cell and spatial epigenomics when combined with multi-omics and AI-driven approaches are making it possible to map the heterogeneity of tumors in ever increasing precision allowing for identification of actionable vulnerabilities. Future research focuses are chromatin subtypes characterization, pharmacological targeting of the epigenome, discovery of synthetic lethality programs and real-time longitudinal assessments of evolving epigenomic states during therapy. It will be necessary to address these challenges, as well as intratumoral heterogeneity, and off-target effects of agents targeting the epigenome at high doses to fully exploit epigenetic vulnerabilities.

To conclude, the combination of mechanisms understanding, biomarker discovery and development, targeted therapeutics will place epigenetics at the center of precision oncology for UBC. These developments have the potential to facilitate early diagnosis, direct rational treatment choice and ultimately improve clinical outcomes in this aggressive and diverse condition.

None.

Ethical policy

Non applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this publication.

Author contributions

Amr Abd-Elraheem Abdo, Ahmed Mohamed Kamel contributed to design of the work, data collection, and drafting the article.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Funding

None.

- Richters A, Aben KK, Kiemeney LA: The global burden of urinary bladder cancer: an update. World J Urol 2020, 38(8): 1895-1904.

- Mori K, Yanagisawa T, Katayama S, Laukhtina E, Pradere B, Mostafaei H, Quhal F, Rajwa P, Moschini M, Soria F: Impact of sex on outcomes after surgery for non-muscle-invasive and muscle-invasive bladder urothelial carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Urol 2023, 41(4): 909-919.

- Mhawech‐Fauceglia P, Cheney RT, Schwaller J: Genetic alterations in urothelial bladder carcinoma: an updated review. Cancer 2006, 106(6): 1205-1216.

- Inanloo SH, Aghamir SMK, Bahri RA, Ghajar HA, Karimian B: Molecular biology, genetic, and epigenetics of bladder tumor. In: Genetics and Epigenetics of Genitourinary Diseases. Epub ahead of print., edn.: Elsevier; 2025: 235-240.

- Loras A, Segovia C, Ruiz-Cerda JL: Epigenomic and metabolomic integration reveals dynamic metabolic regulation in bladder cancer. Cancers 2021, 13(11): 2719.

- Lavallee E, Sfakianos JP, Mulholland DJ: Tumor heterogeneity and consequences for bladder cancer treatment. Cancers 2021, 13(21): 5297.

- Fritz AJ, El Dika M, Toor RH, Rodriguez PD, Foley SJ, Ullah R, Nie D, Banerjee B, Lohese D, Tracy KM et al: Epigenetic-mediated regulation of gene expression for biological control and cancer: cell and tissue structure, function, and phenotype. Results Probl Cell Differ 2022,70: 339-373.

- Schulz WA, Hoffmann MJ: DNA Methylation and Chromatin Regulators in Bladder Cancer. In: Biology of Bladder Cancer: From Molecular Insights to Clinical Strategies. edn.: Springer; 2025: 181-217. Epub ahead of print.

- Ramal M, Corral S, Kalisz M, Lapi E, Real FX: The urothelial gene regulatory network: understanding biology to improve bladder cancer management. Oncogene 2024, 43(1): 1-21.

- Neyret-Kahn H, Fontugne J, Meng XY, Groeneveld CS, Cabel L, Ye T, Guyon E, Krucker C, Dufour F, Chapeaublanc E: Epigenomic mapping identifies an enhancer repertoire that regulates cell identity in bladder cancer through distinct transcription factor networks. Oncogene 2023, 42(19): 1524-1542.

- Schneider AK, Chevalier MF, Derré L: The multifaceted immune regulation of bladder cancer. Nat Rev Urol 2019, 16(10): 613-630.

- Lobo J, Jeronimo C, Henrique R: Targeting the immune system and epigenetic landscape of urological tumors. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21(3): 829.

- Conde M, Frew IJ: Therapeutic significance of ARID1A mutation in bladder cancer. Neoplasia 2022, 31: 100814.

- Baretti M, Yarchoan M: Epigenetic modifiers synergize with immune-checkpoint blockade to enhance long-lasting antitumor efficacy. J Clin Invest 2021,131(16): e151002.

- Lawrentschuk N: New approaches to targeting epigenetic Regulation in Bladder Cancer. Cancers 2023,15(6): 1856

- Thompson D, Lawrentschuk N, Bolton D: New approaches to targeting epigenetic regulation in bladder cancer. Cancers 2023, 15(6): 1856.

- Wan X, Wang D, Zhang X, Xu M, Huang Y, Qin W, Chen S: Unleashing the power of urine-based biomarkers in diagnosis, prognosis and monitoring of bladder cancer. Int J Oncol 2025, 66(3): 18.

- Inayat F, Tariq I, Bashir N, Ullah F, Aimen H: Advancing Genomics in Urologic Tumors: Navigating Precision Therapeutic Pathways. Ann Urol Oncol 2024, 7(1): 33-42.

- Siminovitch L: Advances in cancer research: bench to bedside. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1990, 100(6): 874-878.

- Annese T, Tamma R, De Giorgis M, Ribatti D: microRNAs biogenesis, functions and role in tumor angiogenesis. Front Oncol 2020, 10: 581007.

- Gilyazova I, Enikeeva K, Rafikova G, Kagirova E, Sharifyanova Y, Asadullina D, Pavlov V: Epigenetic and immunological features of bladder cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24(12): 9854.

- Smith VZ: Investigating the relationship between hypoxia and the immune tumour microenvironment in muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Epub ahead of print.: The University of Manchester (United Kingdom); 2023.

- Martinez VG, Munera-Maravilla E, Bernardini A, Rubio C, Suarez-Cabrera C, Segovia C, Lodewijk I, Dueñas M, Martínez-Fernández M, Paramio JM: Epigenetics of bladder cancer: where biomarkers and therapeutic targets meet. Front Genet 2019, 10: 1125.

- Hoffmann MJ, Schulz WA: Alterations of chromatin regulators in the pathogenesis of urinary bladder urothelial carcinoma. Cancers 2021, 13(23): 6040.

- Chaux A: Molecular Mechanisms of Targeted Therapy Resistance in Genitourinary Tumors: A Path to New Therapeutic Horizons. Preprints 2025, Epub ahead of print.

- Akman B, Erkek-Ozhan S: Implications of chromatin modifier mutations in epigenetic regulation of bladder cancer. Urologic Cancers [Internet] 2022, Epub ahead of print.

- Jiao Y, Lv Y, Liu M, Liu Y, Han M, Xiong X, Zhou H, Zhong J, Kang X, Su W: The modification role and tumor association with a methyltransferase: KMT2C. Front Immunol 2024, 15: 1444923.

- Fus ŁP, Górnicka B: Role of angiogenesis in urothelial bladder carcinoma. Cent European J Urol 2016, 69(3): 258.

- Botten GA, Xu J: Genetic and epigenetic dysregulation of transcriptional enhancers in cancer. Ann Rev Cancer Biol 2025, 9(1): 79-97.

- Meghani K, Folgosa Cooley L, Piunti A, Meeks JJ: Role of chromatin modifying complexes and therapeutic opportunities in bladder cancer. Bladder Cancer 2022, 8(2): 101-112.

- Mittal P, Roberts CW: The SWI/SNF complex in cancer—biology, biomarkers and therapy. Nat Rev Clinl Oncol 2020, 17(7): 435-448.

- Zhang S, Lin T, Xiong X, Chen C, Tan P, Wei Q: Targeting histone modifiers in bladder cancer therapy—preclinical and clinical evidence. Nat Rev Urol 2024, 21(8): 495-511.

- Park SH, Fong K-W, Mong E, Martin MC, Schiltz GE, Yu J: Going beyond Polycomb: EZH2 functions in prostate cancer. Oncogene 2021, 40(39): 5788-5798.

- Xu F, Xu X, Deng H, Yu Z, Huang J, Deng L, Chao H: The role of deubiquitinase USP2 in driving bladder cancer progression by stabilizing EZH2 to epigenetically silence SOX1 expression. Transl Oncol 2024, 49: 102104.

- Zhang J, Crumpacker C: HIV UTR, LTR, and epigenetic immunity. Viruses 2022, 14(5): 1084.

- Garg M, Singh R: Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition: Event and core associates in bladder cancer. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2019, 11(1): 150-165.

- Lee K-H, Song CG: Epigenetic regulation in bladder cancer: development of new prognostic targets and therapeutic implications. Transl Cancer Res 2017, 6(Suppl 4).

- Bilgrami SM, Qureshi SA, Pervez S, Abbas F: Promoter hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes correlates with tumor grade and invasiveness in patients with urothelial bladder cancer. Springerplus 2014, 3(1): 178.

- Peixoto AFF: Hypoxic Regulation of Glycosylation in Bladder Cancer. Universidade do Porto (Portugal); 2014.

- Zhu J, Jiang Z, Gao F, Hu X, Zhou L, Chen J, Luo H, Sun J, Wu S, Han Y: A systematic analysis on DNA methylation and the expression of both mRNA and microRNA in bladder cancer. PloS One 2011, 6(11): e28223.

- de Cubas AA, Dunker W, Zaninovich A, Hongo RA, Bhatia A, Panda A, Beckermann KE, Bhanot G, Ganesan S, Karijolich J: DNA hypomethylation promotes transposable element expression and activation of immune signaling in renal cell cancer. JCI insight 2020, 5(11): e137569.

- Ahangar M, Mahjoubi F, Mowla SJ: Bladder cancer biomarkers: current approaches and future directions. Front Oncol 2024, 14: 1453278.

- Jaszek N, Bogdanowicz A, Siwiec J, Starownik R, Kwaśniewski W, Mlak R: Epigenetic Biomarkers as a New Diagnostic Tool in Bladder Cancer—From Early Detection to Prognosis. J Clin Med 2024, 13(23): 7159.

- Yang G, Bondaruk J, Cogdell D, Wang Z, Lee S, Lee JG, Zhang S, Choi W, Wang Y, Liang Y: Urothelial-to-neural plasticity drives progression to small cell bladder cancer. Iscience 2020, 23(6): 101201.

- Neyret-Kahn H, Fontugne J, Meng XY, Groeneveld CS, Cabel L, Ye T, Guyon E, Krucker C, Dufour F, Chapeaublanc E: Epigenomic mapping identifies a super-enhancer repertoire that regulates cell identity in bladder cancers through distinct transcription factor networks. Oncogene 2023, 42(19): 1524-1542.

- Bogale DE: The roles of FGFR3 and c-MYC in urothelial bladder cancer. Discov Oncol 2024, 15(1): 295.

- Nemtsova MV, Kalinkin AI, Kuznetsova EB, Bure IV, Alekseeva EA, Bykov II, Khorobrykh TV, Mikhaylenko DS, Tanas AS, Strelnikov VV: Mutations in epigenetic regulation genes in gastric cancer. Cancers 2021, 13(18): 4586.

- Chen Z, Han F, Du Y, Shi H, Zhou W: Hypoxic microenvironment in cancer: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic interventions. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8(1): 70.

- Koutsi MA, Pouliou M, Champezou L, Vatsellas G, Giannopoulou A-I, Piperi C, Agelopoulos M: Typical enhancers, super-enhancers, and cancers. Cancers 2022, 14(18): 4375.

- Piunti A, Meghani K, Yu Y, Robertson AG, Podojil JR, McLaughlin KA, You Z, Fantini D, Chiang M, Luo Y: Immune activation is essential for the antitumor activity of EZH2 inhibition in urothelial carcinoma. Sci Adv 2022, 8(40): eabo8043.

- Ramakrishnan S, Granger V, Rak M, Hu Q, Attwood K, Aquila L, Krishnan N, Osiecki R, Azabdaftari G, Guru K: Inhibition of EZH2 induces NK cell-mediated differentiation and death in muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Cell Death & Differ 2019, 26(10): 2100-2114.

- Burke B, Eden C, Perez C, Belshoff A, Hart S, Plaza-Rojas L, Reyes MD, Prajapati K, Voelkel-Johnson C, Henry E: Inhibition of histone deacetylase (HDAC) enhances checkpoint blockade efficacy by rendering bladder cancer cells visible for T cell-mediated destruction. Front Oncol 2020, 10: 699.

- Garczyk S, Schneider U, Lurje I, Becker K, Vögeli TA, Gaisa NT, Knüchel R: ARID1A-deficiency in urothelial bladder cancer: No predictive biomarker for EZH2-inhibitor treatment response? PLoS One 2018, 13(8): e0202965.

- Matar M, Prince G, Hamati I, Baalbaky M, Fares J, Aoude M, Matar C, Kourie HR: Implication of KDM6A in bladder cancer. Pharmacogenomics 2023, 24(9): 509-522.

- Wang Z, Muthusamy V, Petrylak DP, Anderson KS: Tackling FGFR3-driven bladder cancer with a promising synergistic FGFR/HDAC targeted therapy. NPJ Precis Oncol2023, 7(1): 70.

- Shorstova T, Foulkes WD, Witcher M: Achieving clinical success with BET inhibitors as anti-cancer agents. Br J Cancer 2021, 124(9): 1478-1490.

- Kobelev M: Prostate cancer lineage plasticity is associated with an altered MYC/MAX cistrome through super-enhancer remodeling. University of British Columbia; 2024.

- Puia D, Ivănuță M, Pricop C: DNA Methylation in Bladder Cancer: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Perspectives—A Narrative Review. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26(15): 7507.

- Zhang H, Pang Y, Yi L, Wang X, Wei P, Wang H, Lin S: Epigenetic regulators combined with tumour immunotherapy: current status and perspectives. Clinl Epigenetics 2025, 17(1): 51.

- Elrakaybi A, Ruess DA, Luebbert M, Quante M, Becker H: Epigenetics in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: impact on biology and utilization in diagnostics and treatment. Cancers 2022, 14(23): 5926.

- Li Q, Lei Y, Zhang P, Liu Y, Lu Q, Chang C: Future challenges and prospects for personalized epigenetics. In book: Personalized Epigenetics 2024, 721-744. Epub ahead of print.

- Hu Y, Shen F, Yang X, Han T, Long Z, Wen J, Huang J, Shen J, Guo Q: Single-cell sequencing technology applied to epigenetics for the study of tumor heterogeneity. Clin Epigenetics 2023, 15(1): 161.

- Lee RY, Ng CW, Rajapakse MP, Ang N, Yeong JPS, Lau MC: The promise and challenge of spatial omics in dissecting tumour microenvironment and the role of AI. Front Oncol 2023, 13: 1172314.

- Lin N, Zhou Y, Li Y, Lin L, Zhu L, Chen J: Circulating tumor DNA and urinary tumor DNA: useful biomarkers for bladder cancer detection. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2025, 25(11): 817-828.

- Rehman H, Chandrashekar DS, Balabhadrapatruni C, Nepal S, Balasubramanya SAH, Shelton AK, Skinner KR, Ma A-H, Rao T, Agarwal S: ARID1A-deficient bladder cancer is dependent on PI3K signaling and sensitive to EZH2 and PI3K inhibitors. Jci Insight 2022, 7(16): e155899.

- Zakari S, Niels NK, Olagunju GV, Nnaji PC, Ogunniyi O, Tebamifor M, Israel EN, Atawodi SE, Ogunlana OO: Emerging biomarkers for non-invasive diagnosis and treatment of cancer: a systematic review. Front Oncol 2024, 14: 1405267.

- Christensen E, Birkenkamp-Demtröder K, Sethi H, Shchegrova S, Salari R, Nordentoft I, Wu H-T, Knudsen M, Lamy P, Lindskrog SV: Early detection of metastatic relapse and monitoring of therapeutic efficacy by ultra-deep sequencing of plasma cell-free DNA in patients with urothelial bladder carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2019, 37(18): 1547-1557.

- Kiruba B, Narayan PA, Raj B, Raj SR, Mathew SG, Lulu SS, Sundararajan V: Intervention of machine learning in bladder cancer research using multi-omics datasets: systematic review on biomarker identification. Discov Oncol 2025, 16(1): 1010.

- Mihai IM, Wang G: Biomarkers for predicting bladder cancer therapy response. Oncol Res 2025, 33(3): 533.

- Reis SM: Uncovering the Role of Epigenetic Mechanisms in Bladder Cancer Aggressiveness: From Biology to Clinical Setting. Universidade do Porto (Portugal); 2021.

- Rani B, Ignatz-Hoover JJ, Rana PS, Driscoll JJ: Current and emerging strategies to treat urothelial carcinoma. Cancers 2023, 15(19): 4886.

- van der Vos K, Vis D, Nevedomskaya E, Kim Y, Choi W, McConkey D, Wessels L, van Rhijn B, Zwart W, van der Heijden M: Epigenetic profiling demarcates molecular subtypes of muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Sci Rep 2020, 10(1): 10952.

- Huang P, Wang J, Yu Z, Lu J, Sun Z, Chen Z: Redefining bladder cancer treatment: innovations in overcoming drug resistance and immune evasion. Front Immunol 2025, 16: 1537808.

- Xiao Y, Jin W, Qian K, Wu K, Wang G, Jiang W, Cao R, Ju L, Zhao Y, Zheng H: Emergence of an adaptive epigenetic cell state in human bladder urothelial carcinoma evolution. bioRxiv 2021, Epub ahead of print.

- Ferreira MFS: Epimarkers for Bladder Cancer Diagnosis and Monitoring (EpiBlaC). Universidade do Porto (Portugal); 2023.

- Yoshihara K, Ito K, Kimura T, Yamamoto Y, Urabe F: Single-cell RNA sequencing and spatial transcriptome analysis in bladder cancer: Current status and future perspectives. Bladder Cancer 2025, 11(1): 23523735251322017.

- Kwong JCC: Improving Prognostication in Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer Using Artificial Intelligence. University of Toronto (Canada); 2024.

Annals of urologic oncology

p-ISSN: 2617-7765, e-ISSN: 2617-7773

Copyright © Ann Urol Oncol. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License.

Copyright © Ann Urol Oncol. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License.

Submit Manuscript

Submit Manuscript