Review Article | Open Access

Evolving Precision Therapy Paradigm against Adrenocortical Carcinoma

Declan Moore1, Wayway Li11College of Science, Jackson State University, Main Campus, Jackson, 39217, Mississipi, USA.

Correspondence: Wayway Li (College of Science, Jackson State University, Main Campus, 1400 John R. Lynch Street, Jackson, 39217, Mississipi, USA; Email: 8756LV81@outlook.com).

Annals of Urologic Oncology 2025, 8(4): 177-187. https://doi.org/10.32948/auo.2025.12.05

Received: 28 Sep 2025 | Accepted: 13 Dec 2025 | Published online: 20 Dec 2025

Key words adrenocortical carcinoma, targeted therapy, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, immunotherapy, antibody-drug conjugates, cancer vaccine

Mitotane, an adrenolytic agent, along with cytotoxic chemotherapy has historically dominated the therapeutic landscape for ACC. Although the FIRM-ACT trial has established the combination of etoposide, doxorubicin, and cisplatin with mitotane (EDP-M) as key first-line systemic therapy, it only yields a 23% objective response rate, with 5 and 14.8 months of median progression-free survival (PFS) and median OS respectively [8]. Other cytotoxic regimens have demonstrated only little to no benefit and are typically used for subsequent lines of therapy or for patients unable to tolerate EDP-M [9]. Mitotane therapy has its own limitations including, but not limited to, delayed achievement of therapeutic plasma concentrations, variable pharmacokinetics driven by CYP3A4 induction, and significant gastrointestinal and neurologic toxicity [10, 11]. Overall, better-tolerated, and more effective therapeutic strategies need to be developed to tackle ACC.

Advances in genomics and multi-omics profiling during the last decade have transformed our understanding of ACC biology. Three major molecular subtypes (COC1-COC3) have been established, each with distinctive genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenetic features, with markedly unique clinical outcomes [12]. Recurring alterations in different oncogenic pathways leading to IGF2 overexpression, Wnt/β-catenin dysregulation through CTNNB1 or ZNRF3 mutations, disruption of cell-cycle and p53-dependent apoptotic control, chromatin remodeling defects, and aberrations in DNA damage repair mechanisms have been found to be associated with tumorigenesis in ACC [4, 6]. Aberrations in tumor microenvironment, marked by immune exclusion and angiogenic remodeling, further aid in the tumor heterogeneity and therapeutic resistance in ACCs [13, 14]. Therefore, integrating molecular profiling into clinical decision-making is suggested to identify actionable vulnerabilities, which will improve patient stratification, and refine the deployment of targeted therapies, immunotherapies, and combination strategies [15, 16]. This approach is potentially critical for rare cancers including ACC, where limited patient numbers, conventional trial designs, and heterogeneous treatment responses mask the therapeutic innovation.

In this review, we explore genomic, epigenomic, and microenvironmental insights into ACC biology, and present rapidly evolving precision-therapy landscape against this cancer. In addition, we discuss ongoing advancements in targeted agents, immunotherapy, radiopharmaceuticals and next-generation precision modalities, all of which have the potential to delineate a promising framework for personalized treatment of ACC, highlighting a future with translational opportunities reshaping the clinical outcomes in ACC patients.

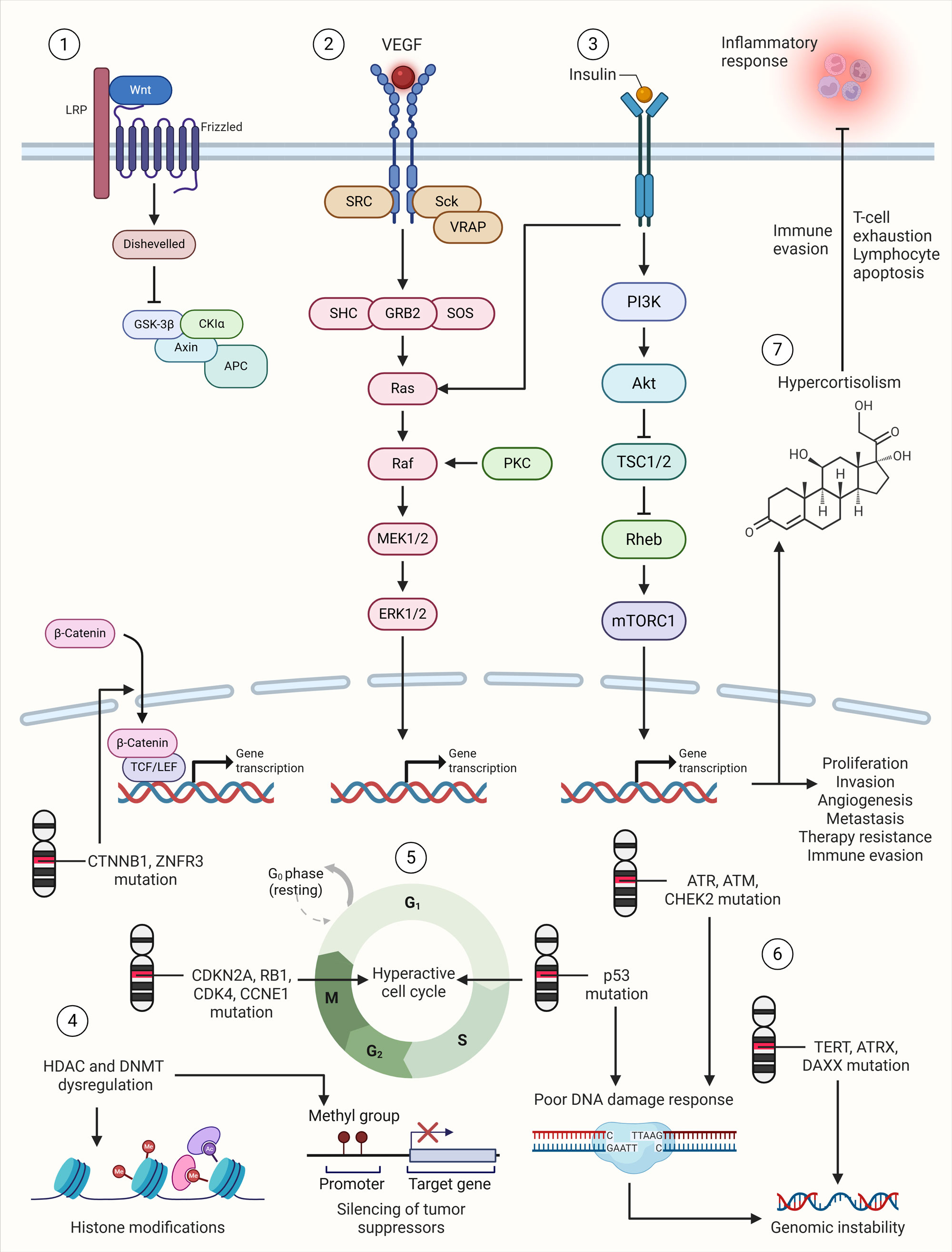

In the context of oncogenic signaling pathways, the IGF2/IGF1R signaling axis represents one of the most consistently dysregulated pathways in ACC, with IGF2 overexpression occurring in up to 90% of tumors [13]. IGF2 hyperactivation is attributed to aberrant imprinting at chromosome 11p15. This event promotes mitogenic and anti-apoptotic signaling via activation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR and RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK axes, leading to cell-cycle progression, metabolic adaptation, and survival of cancer cells in ACCs [13, 18]. Aberrant activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway due to somatic mutations in CTNNB1, primarily affecting exon 3 phosphorylation sites, leads to β-catenin stabilization and nuclear accumulation. This drives transcription of genes involved in proliferation, invasion, and cellular dedifferentiation [12, 17]. Loss-of-function of ZNRF3, a negative regulator of Wnt signaling leads to uncontrolled pathway activation, correlating with aggressive disease [19, 20]. Disruption of cell-cycle checkpoints, such as mutations in TP53 tumor suppressor are frequently observed in both sporadic tumors and those associated with Li-Fraumeni syndrome. These events compromise DNA damage responses, and promote genomic instability and resistance to apoptosis. Concomitantly, alterations in CDKN2A, RB1, CDK4, and CCNE1 deregulate G1/S transition, fostering unchecked proliferation [13, 21]. Alterations in mismatch repair, homologous recombination repair, and DNA damage responses regulators, such as ATR, ATM, and CHEK2, are evident in ACCs. These events contribute to genomic instability, mutational load, and therapeutic resistance [3, 17]. Mismatch repair deficiency associates ACC with Lynch syndrome. ACC tumors with microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) are rare (~3%), but these tumors demonstrate enhanced responsiveness to immune checkpoint inhibition [22]. Mutations in epigenetic factors TERT, ATRX, and DAXX are associated with disrupted telomere maintenance, leading to replicative immortality and facilitating chromosomal instability [23, 24]. Promoter hypermethylation and CIMP-high states lead to inhibition of tumor suppressor genes and modulation of steroidogenic pathways, resulting in poor-prognosis of COC3 subtype. Therefore, targeting epigenetic regulators, such as HDAC and DNMT, is a key therapeutic frontier in ACC as well [25, 26]. Aberrant activation of cAMP-PKA signaling through PRKAR1A loss or pathway dysregulation also contributes to abnormal steroidogenesis and accelerated proliferation of cancer cells in ACCs [27, 28]. Overall, all these signaling axes intertwine with intrinsic oncogenic pathways (Figure 1), amplifying tumor aggressiveness and complicating therapeutic intervention.

Figure 1. Genomic and molecular landscape of adrenocortical carcinoma. 1) Aberrant activation of Wnt signaling through mutations in CTNNB1 and loss of ZNRF3, leads to β-catenin stabilization, nuclear accumulation, and transcription of genes involved in cell proliferation and invasion. 2) VEGF signaling promotes endothelial cell proliferation and angiogenesis, essential for tumor growth, nutrient supply, and metastasis. 3) IGF2 overexpression activates mitogenic and anti-apoptotic signaling through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK axes, driving tumor cell survival and proliferation. 4) Modifications in histones and DNA methylation and acetylation patterns due to HDAC and DNMT dysregulation contribute to silencing of tumor suppressor genes in aggressive ACC subtypes. 5) Mutations in key cell-cycle regulators (e.g., CDKN2A, RB1, CDK4, CCNE1) and DNA damage repair genes (e.g., TP53) compromise cell-cycle checkpoints, contributing to hyperactive cell cycle and tumor progression. 6) Mutations in DNA damage repair genes (e.g., TP53, ATM, ATR, CHEK2) lead to poor DNA damage response, which along with mutations in TERT, ATRX and DAXX results in genomic instability. 7) Hypercortisolism in ACC promotes immune evasion by inducing T-cell exhaustion and lymphocyte apoptosis, further complicating therapeutic efficacy.

Figure 1. Genomic and molecular landscape of adrenocortical carcinoma. 1) Aberrant activation of Wnt signaling through mutations in CTNNB1 and loss of ZNRF3, leads to β-catenin stabilization, nuclear accumulation, and transcription of genes involved in cell proliferation and invasion. 2) VEGF signaling promotes endothelial cell proliferation and angiogenesis, essential for tumor growth, nutrient supply, and metastasis. 3) IGF2 overexpression activates mitogenic and anti-apoptotic signaling through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK axes, driving tumor cell survival and proliferation. 4) Modifications in histones and DNA methylation and acetylation patterns due to HDAC and DNMT dysregulation contribute to silencing of tumor suppressor genes in aggressive ACC subtypes. 5) Mutations in key cell-cycle regulators (e.g., CDKN2A, RB1, CDK4, CCNE1) and DNA damage repair genes (e.g., TP53) compromise cell-cycle checkpoints, contributing to hyperactive cell cycle and tumor progression. 6) Mutations in DNA damage repair genes (e.g., TP53, ATM, ATR, CHEK2) lead to poor DNA damage response, which along with mutations in TERT, ATRX and DAXX results in genomic instability. 7) Hypercortisolism in ACC promotes immune evasion by inducing T-cell exhaustion and lymphocyte apoptosis, further complicating therapeutic efficacy.

Angiogenic program driven by VEGF, FGF2, and other pro-vasculogenic cytokines in the tumor microenvironment also promotes tumor progression in ACC, leading to endothelial proliferation, improved nutrient availability, and enhanced vascular permeability [21, 38]. Advanced stage ACC also shows increased serum levels of VEGF and high VEGFR expression on the surface of tumor cells. This indirectly suggests that angiogenic signaling plays key roles in tumor maintenance and survival in ACC [39, 40]. On the other hand, vasculogenic mimicry is also a key feature of ACCs, where vessel-like structures independent of endothelial cells are formed, thereby providing an additional survival edge to the tumors, other than conventional angiogenic pathways [39]. This alternative vascular channel formation capacity also helps metastatic spread of the disease, support growth under hypoxic conditions, and promote resistance against VEGF-targeted therapies, as demonstrated by clinical trials of first-generation VEGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), such as sorafenib, sunitinib, and axitinib in ACCs [38, 41]. Tumor microenvironment also has cancer-associated fibroblasts, extracellular matrix, and stromal signaling molecular networks which promote tumor proliferation and invasion. Most notably, TGF-β1 is secreted by both tumor cells and stromal elements, and aids in developing a pro-invasive phenotype by promoting epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, and by limiting immune effector cell activation [30]. Overall, tumor microenvironment in ACC is a complex, multilayered hurdle against therapeutic success.

Targeted therapies against oncogenic signaling pathways

The IGF pathway has long been regarded as one of the most actionable oncogenic drivers in ACC due to the near-universal overexpression of IGF2 and its downstream activation of IGF-1R-mediated proliferative cascades [13]. Early preclinical studies demonstrated potent anti-tumor effects with IGF1R inhibition, including growth suppression and apoptotic induction in ACC cell lines, particularly when combined with mitotane [42]. Figitumumab and cixutumumab are key monoclonal antibodies targeting IGF-1R. Treatment with these monoclonal antibodies in ACC has shown good tolerability in early trials but the objective response rates have been very limited [43]. In a phase I study with the combination of cixutumumab and mTOR inhibitor temsirolimus, only 42% of patients showed disease stability for more than six months [44]. On the other hand, another trial reported partial responses in only 5% of patients when treated with the combination of cixutumumab and mitotane in the first-line setting [45]. Notably, despite having good responses in low-grade tumors, dual IGF-1R/insulin receptor inhibitor, linsitinib, failed to meet its primary endpoint of OS in a phase III randomized, placebo-controlled trial [46]. Overall, these data indicates that effective therapeutic exploitation may need biomarker-driven patient selection, more advanced combinatorial strategies, or next-generation inhibitors which are capable of overcoming pathway compensation. Although mTOR inhibitors have shown poor performance in advanced ACC, preclinical data suggests that these compounds synergize well with IGF axis inhibition. In addition, their combination with immunotherapy (e.g., eganelisib + nivolumab) has potential for multi-pathway targeting approaches [47]. The complexity of such an IGF-mTOR signaling targeted approach however illustrates the need for better strategies to limit the pathway cross-talk, resistance mechanisms, and tumor heterogeneity.

CTNNB1 mutations are highly prevalent in ACCs along with functional loss of ZNRF3, hence providing another attractive therapeutic avenue for the treatment of ACCs. Preclinical studies with small-molecule inhibitors of TCF/β-catenin complex (e.g., PKF115-584) or β-catenin knockdown have achieved effective reduction in proliferation and induction of apoptosis in ACCs [17]. These findings confirm the oncogenic dependency of ACC on Wnt signaling and provide proof of principle for pathway-directed interventions. However, the clinical translation of Wnt-targeting agents remains limited. The difficulty of achieving selective inhibition without significant off-target effects, given the pathway’s essential role in normal tissue homeostasis, has hindered the development of clinically viable inhibitors. Moreover, the extensive integration of Wnt signaling with adrenal development and zonation pathways creates challenges in balancing therapeutic efficacy with preservation of endocrine function [20]. Despite these barriers, the identification of Wnt-activated molecular clusters within ACC and the availability of next-generation inhibitors targeting upstream regulators (e.g., porcupine inhibitors) suggest that Wnt-directed therapy may eventually find a role in biomarker-defined patient subsets or in combination with other pathway inhibitors.

TKIs constitute one of the most extensively explored classes of targeted therapies in ACC, given the strong biological rationale for targeting angiogenesis, growth factor signaling, and metastatic pathways. However, clinical outcomes across most VEGFR-focused TKIs have been variable and generally modest. Early trials of sorafenib, sunitinib, and axitinib demonstrated minimal anti-tumor activity (Table 1). In prospective phase II studies, all three agents yielded low disease control rates and median PFS values under three months, with no durable objective responses [38, 41, 48]. The unique vascular biology of ACC is responsible for limited efficacy of these treatment, as marked by vasculogenic mimicry, high stromal resistance, and activation of multiple compensatory angiogenic pathways [39, 49]. On the other hand, promising anti-tumor activity has been reported for cabozantinib, a multi-kinase inhibitor targeting VEGFR, MET, AXL, and RET. Partial responses and prolonged disease control along with median PFS of 6-16 weeks in heavily pretreated patients have been observed for cabozantinib treatment in ACCs in retrospective and early-phase studies [50, 51]. Broader inhibition of metastatic and invasive signaling pathways like MET and AXL signaling, is the key therapeutic advantage of cabozantinib treatment in ACCs, leading to active suppression of aggressive tumor behavior. Synergistic targeting of EGFR and IGF1R has also been fruitful in ACCs as shown by preclinical studies where combination blockade significantly reduced tumor growth relative to monotherapy [52]. Although these findings highlight dual-pathway blockade as a key advancement in overcoming resistance to single-agent TKIs, clinical evidence is still lacking. Taken together, while VEGFR TKIs show limited clinical benefit, cabozantinib treatment and the rational of combining multiple TKIs represent meaningful advances in the precision-therapy against ACCs.

Pioglitazone and rosiglitazone are well-established peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) agonists, which have shown considerable anti-tumor activity in ACC models. These agents not only promote apoptosis induction, reduce angiogenesis, and inhibit proliferative pathways, such as PI3K/AKT and ERK1/2, but also limit pro-survival signals including VEGF and Bcl-2 [53, 54]. Reductions in tumor volume and microvessel density along with an increase in CXCL12 expression, a chemokine associated with improved prognosis, have been observed with rosiglitazone treatment in animal models [55]. However, clinical benefit of these therapies in ACCs is still limited as the therapeutic potential of PPARγ modulation remains largely unexplored. Therefore, PPARγ agonists are attractive candidates to be tried as a treatment for ACCs in future combination regimens.

As cell-cycle deregulation and disruption of DNA damage response pathways are key pathogenesis mechanisms in ACC, targeting these pathways are of key importance. In CTNNB1-mutant cell lines, nutlin-3a, an MDM2 inhibitor, has shown great preclinical activity by inducing apoptosis and reducing hormone production [56]. On the other hand, BI-2536, a PLK1 inhibitor, has shown the ability to effectively restore p53 signaling, disrupt centrosome homeostasis, and induce apoptosis in ACC cells in vitro [57, 58]. CDK4/6 inhibitors (e.g., palbociclib, ribociclib), known for cell-cycle blockade, have also shown promising preclinical results by reducing cell viability and promoting senescence or apoptosis in ACC cells in vitro [59]. Treatment with PARP inhibitors, such as olaparib, rucaparib, and talazoparib is primarily supported by alterations in homologous recombination repair, though their efficacy in ACC remains to be fully validated.

Immunotherapy and immune modulators

Therapeutic landscape for various solid malignancies including ACC has been reshaped with the advent of immunotherapies and immune modulators (Table 1). Variable outcomes in ACC have been observed with monotherapy of ICIs targeting PD-1 or PD-L1, resulting in modest overall response rates relative to other solid tumors. In a multi-cohort phase Ib study, partial responses in 6% of patients and disease stabilization in 42% were observed with avelumab in ACC patients, which led to a median PFS of 2.6 months [60]. On the other hand, in a phase II trial with previously treated patients, nivolumab treatment stabilized the disease in only 20% of individuals but objective responses were not achieved, and rapid disease progression was observed after only a median of two doses [35]. Pembrolizumab treatment in ACCs has however shown more favorable activity in ACCs. It achieved partial responses in 14-23% of patients and disease control rates ranging from 41% to 64% in two independent prospective trials [36, 61]. These outcomes highlight that the overall responsiveness of ACC to checkpoint inhibition monotherapy is primarily modest. The reason behind this includes tumor heterogeneity to microsatellite instability, immune cell infiltration, and systemic cortisol levels. As discussed previously, ACC tumors have low tumor mutational burden, but a small subset of tumors display mismatch repair deficiency and MSI-H, often in the context of Lynch syndrome. These tumors are highly susceptible to ICI therapy [31]. In line with this, 33% of MSI-H patients achieved partial response and an additional 33% achieved durable stable disease for more than 24 months with pembrolizumab treatment [61]. Similarly, durable responses towards combination immunotherapies have also largely been confined to patients with MSI-H tumors [37]. On the other hand, as the vast majority of ACC cases represent microsatellite-stability, monotherapy with ICIs is often associated with limited responsiveness in these patients. Overall, these findings highlight the need for molecular stratification, and MSI-H status can serve as biomarkers of immunotherapy efficacy in ACCs.

Combination therapies targeting CTLA-4 and PD-1 have shown promising immunologic activation in different cancer types including ACC. In this line, dual therapy with ipilimumab and nivolumab has shown partial responses in 19% and stable disease in 33%, with overall clinical benefit in 52% of patients in a rare tumor cohort of the CA209-538 study [37]. Despite this, the toxicities associated with CTLA-4 inhibition warrant careful patient selection, especially in cases where cortisol-secreting disease can lead to immunotherapy-related adrenal crises. Profound immunosuppression and aberrant angiogenesis characteristic of ACC also support the combination strategies integrating VEGFR-targeted agents and ICIs. In this line, a multi-cohort phase II study has evaluated the combination of cabozantinib with atezolizumab, and reported partial responses in 8.3% and durable clinical benefit in select ACC patients [62]. However, limited (2.9 months) median PFS was achieved in this study, mainly attributed to the inclusion of heavily pretreated patients. A phase II trial of camrelizumab plus apatinib combination achieved a 50% objective response rate and 95% disease control rate, with a median PFS of 12.6 months and median OS of 20.9 months. These compelling results substantially exceed the outcomes observed with monotherapy ICIs [63]. Mechanistically, increased tumor-infiltration of CD8⁺ T cells, enhanced clonal overlap between circulating and intratumoral lymphocytes, and reductions in immunosuppressive CD4⁺ cells, were the key behind synergistic effects observed with the combination of angiogenesis inhibition and PD-1 blockade [63].

ACCs exhibit high expression of IL-13Rα2 receptor, making it a promising target. Treatment with recombinant fusion toxin IL-13-Pseudomonas exotoxin (IL-13-PE) in a phase I study has shown disease stabilization for 2 to 5.5 months in IL-13Rα2-positive ACC patients [64]. On the other hand, CAR-T cell therapies against IL-13Rα2 have also shown considerable antitumor activity in preclinical studies with ACC cell lines [65]. Therefore, solid-tumor CAR-T engineering and receptor-directed cellular immunotherapy, particularly in combination with tumor microenvironment modulators, has become a key therapeutic frontier in ACC treatment. Immunosuppressive effects of endogenous cortisol have led to the therapeutic strategies entailing modulation of the glucocorticoid signaling axis in augmenting immunotherapy efficacy. In this context, relacorilant is a selective glucocorticoid receptor modulator. It has been shown to reverse cortisol-mediated immune dysfunction [66-68]. Currently, a phase Ib trial is evaluating the combination of relacorilant with pembrolizumab in cortisol-producing ACC. The aim of the study is to test whether this combination can restore T-cell function while simultaneously enabling effective checkpoint blockade. Promising results from the trials will serve as a base for the establishment of integrated immunotherapeutic strategy moving forward.

Next-generation precision modalities

Radiopharmaceutical approaches in ACC capitalize on the unique steroidogenic biology of adrenal cortical cells. ¹²³I-IMTO and its therapeutic analogue ¹³¹I-IMTO exploit adrenal-specific binding to 11β-hydroxylase, enabling both diagnostic imaging and targeted radionuclide therapy. In a cohort of 49 patients, 27% demonstrated high ¹²³I-IMTO uptake, and among those treated with ¹³¹I-IMTO, partial response or sustained disease stabilization was observed in 60% of evaluable individuals, with a median PFS of 14 months [69]. Broader target binding across metastatic lesions was observed with a subsequent generation agent, ¹³¹I-IMAZA. Although only 19% of patients receiving this therapy showed strong uptake, 42% achieved considerable disease stabilization with a median PFS of 14.3 months [70]. Targeted therapy with ⁹⁰Y/¹⁷⁷Lu-DOTATOC has shown modest activity in patients with sufficient somatostatin receptor expression, though the expression of the receptor is not uniformly high in ACC. Two out of 19 patients have shown robust uptake and received radionuclide treatment in a prospective study. As a result, one of them developed a partial response lasting 12 months [71]. Such treatment approaches highlight the potential for highly selective molecular imaging to guide individualized therapy, though the treatment eligible population is small.

Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) offer another treatment frontier for targeted drug delivery by combining antigen specificity with cytotoxic payloads [72]. ABBV-176, which targets the prolactin receptor (PRLR), was evaluated in a phase I trial that included two ACC patients. Unfortunately, no substantial clinical responses were observed along with hematologic and hepatic toxicities, leading to early trial termination [73]. The Notch ligand DLK1 is overexpressed in ACC, leading to tumor stemness. ADCT-701, a pyrrolobenzodiazepine dimer-conjugated ADC, has been developed to target DLK1. Preclinical studies have shown potent antitumor activity in ACC xenografts [74]. On the other hand, ADCT-211, a next-generation PBD-based ADC targeting IL-13Rα2 receptor, has shown compelling preclinical efficacy along with complete tumor regression in ACCs [75]. Although hurdles like antigen heterogeneity, payload toxicity, and delivery optimization exist, ADCs are a promising class of precision therapies to limit ACC tumor burden with high specificity.

Amplifying T-cell responses against tumor-associated antigens by the use of therapeutic vaccines in ACCs is a key avenue to overcome the inherent lack of tumor immunogenicity in these tumors. In this line, EO2401 incorporates peptides that mimic ACC-associated antigens, such as IL13RA2, BIRC5, and FOXM1. Its combination with nivolumab in a phase I/II study has shown partial responses in 12% and disease stabilization in 24% of patients, though median PFS was reported to be just 1.9 months [76]. On the other hand, mRNA-0523-L001, an individualized neoantigen vaccine designed for endocrine malignancies including ACC, is also being tested in a phase I study. mRNA vaccines have the potential to become a highly personalized strategy with durable and potent immune responses by leveraging next-generation sequencing and patient-specific neoepitopes. Another rapidly expanding frontier in ACC treatment is cellular immunotherapies, primarily driven by lineage-restricted surface antigens and CAR engineering. ACC, along with multiple pediatric and adult solid tumors, express B7-H3. B7-H3-CAR-T cells have shown great antitumor activity in preclinical ACC models [77]. B7-H3 CAR-T therapy is being tested in pediatric solid tumors, including ACC, in a phase I trial. ROR1 is another tumor-associated antigen that is being explored in ACC. CRISPR-mediated glucocorticoid receptor knockout has been shown to enhance the antitumor activity of ROR1-CAR-T cells in preclinical ACC models. In line with this, IL-13Rα2-CAR-T cells have also shown tumor inhibition capacity in ACC preclinical studies [65]. Although clinical translation is still in early stages, CAR-T and cellular therapies, particularly in combination with microenvironmental modulation, represent a promising future for different subsets of ACC patients.

Advances in nanotechnology, bioengineering, and artificial intelligence (AI) have been instrumental to improve drug delivery, immune activation, and precision therapy in ACC. Delivery vehicles with copper-based nanomaterials and other engineered nanoparticles have shown promising results in enhancing intratumoral drug penetration and generating imaging contrast for ACC lesions. Tumor microenvironment modulating nanoparticles have been shown to modulate stromal architecture and facilitate immunogenic cell death [78, 79]. Emerging bioengineering strategies have also shown systemic immunomodulatory effects in early studies, suggesting their role in altering stromal and immune cell activation patterns, and their synergy with immunotherapy [80]. AI has been applied to diverse cancer contexts [81], and holds enormous potential for ACC. Based on their ability to integrate multi-omics data, imaging biomarkers, and clinical variables, AI systems have shown potential to facilitate early diagnosis, patient stratification, and therapy selection, thereby playing an active role in the development of precision therapy.

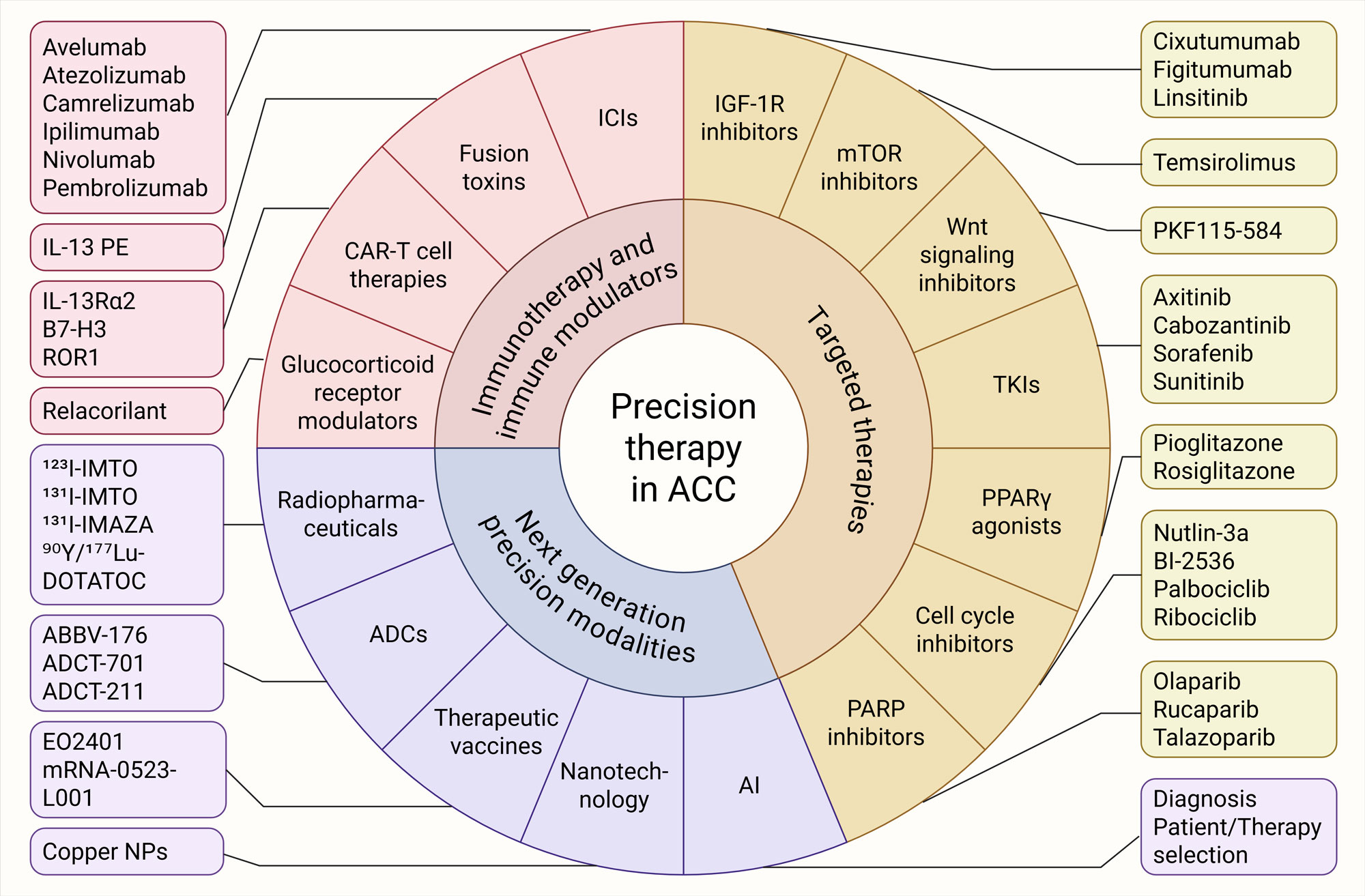

Figure 2. Evolving precision-guided therapeutics in ACC. Targeted therapies (IGF-1R inhibitors, mTOR inhibitors, Wnt signaling inhibitors, TKIs, cell-cycle inhibitors, and PARP inhibitors), immunotherapy and immune modulators (ICIs along with their combination strategies, fusion toxins, CAR-T therapies, and glucocorticoid receptor modulators) and next-generation precision modalities (radiopharmaceuticals, ADCs, therapeutic vaccines, nanotechnology and AI) represent key approaches for personalized therapy against ACC. AI: Artificial intelligence, ADC: Antibody-drug conjugate, ICI: Immune checkpoint inhibitor, NP: Nanoparticle, TKI: Tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Figure 2. Evolving precision-guided therapeutics in ACC. Targeted therapies (IGF-1R inhibitors, mTOR inhibitors, Wnt signaling inhibitors, TKIs, cell-cycle inhibitors, and PARP inhibitors), immunotherapy and immune modulators (ICIs along with their combination strategies, fusion toxins, CAR-T therapies, and glucocorticoid receptor modulators) and next-generation precision modalities (radiopharmaceuticals, ADCs, therapeutic vaccines, nanotechnology and AI) represent key approaches for personalized therapy against ACC. AI: Artificial intelligence, ADC: Antibody-drug conjugate, ICI: Immune checkpoint inhibitor, NP: Nanoparticle, TKI: Tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

|

Table 1. Therapeutic trials in adrenocortical carcinoma with targeted and immunotherapies. |

|||||

|

Trial |

Drugs |

Mechanism of action |

Phase |

Primary outcomes |

Status |

|

NCT00453895 (SIRAC) |

Sunitinib |

VEGFR TKI |

II |

ORR, PFS (primary) |

Terminated |

|

NCT01255137 |

Axitinib |

VEGFR TKI |

II |

ORR (primary), OS, DCR, PFS, safety (secondary) |

Terminated |

|

NCT02637531 (MARIO-1) |

Nivolumab + IPI-549 (Eganelisib) |

ICI + PI3K inhibitor |

I |

DLT, ORR, DOR, PFS, OS, IPI−549 plasma concentrations |

Active, not recruiting |

|

NCT02720484 |

Nivolumab |

ICI (single-agent) |

II |

ORR (primary), PFS, OS, Safety (secondary) |

Terminated |

|

NCT02721732 |

Pembrolizumab |

ICI (single-agent) |

II |

NPR (primary), ORR, PFS, Safety (secondary) |

Active, not recruiting |

|

NCT02867592 |

Cabozantinib |

VEGFR TKI |

II |

ORR (primary), Safety, Tissue-banking (secondary) |

Active, not recruiting |

|

NCT03333616 |

Nivolumab + Ipilimumab |

ICI (dual) |

II |

ORR (primary), DOR, PFS, OS, Safety (secondary) |

Terminated |

|

NCT03370718 |

Cabozantinib |

VEGFR TKI |

II |

PFS4 (primary), ORR, PFS, OS, Safety (secondary) |

Terminated |

|

NCT03612232 (CaboACC) |

Cabozantinib |

VEGFR TKI |

II |

PFS4 (primary), ORR, PFS, OS, Safety (secondary) |

Active, not recruiting |

|

NCT04187404 (SPENCER) |

Nivolumab + EO2401 |

ICI + Vaccine |

I/II |

Safety (primary), PFS, OS, Immuno-genicity (secondary) |

Terminated |

|

NCT04318730 |

Apatinib + Camrelizumab |

VEGFR TKI + ICI |

II |

ORR (primary), OS, DCR, PFS, safety (secondary) |

Recruiting |

|

NCT04400474 (CABATEN/ GETNE-T1914) |

Cabozantinib + Atezolizumab |

VEGFR TKI + ICI |

II |

ORR (primary), PFS, OS, Safety (secondary) |

Terminated |

|

NCT05036434 (ACCOMPLISH) |

Lenvatinib + Pembrolizumab |

VEGFR TKI + ICI |

II |

ORR (primary), DCR |

Enrolling by invitation |

|

NCT05634577 |

Pembrolizumab + Mitotane |

ICI + Steroidogenesis Inhibitor |

II |

ORR (primary) |

Terminated |

|

NCT06006013 |

Cabozantinib + Pembrolizumab |

VEGFR TKI + ICI |

II |

ORR (primary), PFS, OS, Safety (secondary) |

Active, not recruiting |

|

NCT06066333 |

Pembrolizumab + Radiotherapy |

ICI + Radiotherapy |

II |

Safety (primary) |

Active, recruiting |

|

SAT−175 Trial |

Cabozantinib |

VEGFR TKI |

II |

PFS (primary), ORR, OS, Safety (secondary) |

Terminated |

|

DCR: Disease control rate, DLT: Dose-limiting toxicity, DOR: Duration of response, ICI: Immune checkpoint inhibitor, ORR: Objective response rate, OS: Overall survival, PFS: Progression-free survival, TKI: Tyrosine kinase inhibitor. |

|||||

Notable progress has been made toward a more integrated, multi-dimensional treatment paradigm for ACC despite the above discussed limitations. Combination therapies are the key advancements that allow targeting of different biological vulnerabilities. VEGFR TKIs combined with PD-1 inhibitors, IGF1R with mTOR inhibition, epigenetic modulators with immunotherapy, or glucocorticoid receptor modulation with ICIs are all aiding in counteract multiple resistance pathways. Combining genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and endocrine profiling into a clinically meaningful framework represents the future of therapeutic treatment of cancer, in general, and ACC, in particular. This may involve expanding molecular classifiers similar to COC1-COC3 with additional immune and metabolic information. On the other hand, innovative trial designs, including adaptive platform trials, Bayesian models, and multinational collaborations, will be essential to evaluate emerging therapies more efficiently, as ACC represents a rare cancer type. Alongside this, AI has significant potential to contribute to predictive modeling, early relapse detection, and multi-omics integration [82, 83]. Therapeutic success can also be enhanced by targeting stromal and metabolic factors, such as SOAT1 [84], cholesterol trafficking pathways, or vasculogenic mimicry. Overall, integrating multi-omics insights with next-generation therapeutic technologies promises the development of individualized management strategies to tackle ACC in the future.

None.

Ethical policy

Non applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this publication.

Author contributions

DM, WWL contributed to design of the work, data collection, and drafting the article. WWL revised the draft manuscript and approved the final submission.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Funding

None.

- Shariq OA, McKenzie TJ: Adrenocortical carcinoma: current state of the art, ongoing controversies, and future directions in diagnosis and treatment. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 2021, 12: 20406223211033103.

- Libé R, Huillard O: Adrenocortical carcinoma: Diagnosis, prognostic classification and treatment of localized and advanced disease. Cancer Treat Res Commun 2023, 37: 100759.

- Crona J, Beuschlein F: Adrenocortical carcinoma - towards genomics guided clinical care. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2019, 15(9): 548-560.

- Sun J, Huai J, Zhang W, Zhao T, Shi R, Wang X, Li M, Jiao X, Zhou X: Therapeutic strategies for adrenocortical carcinoma: integrating genomic insights, molecular targeting, and immunotherapy. Front Immunol 2025, 16: 1545012.

- Glenn JA, Else T, Hughes DT, Cohen MS, Jolly S, Giordano TJ, Worden FP, Gauger PG, Hammer GD, Miller BS: Longitudinal patterns of recurrence in patients with adrenocortical carcinoma. Surgery 2019, 165(1): 186-195.

- Singer AE, Kathuria-Prakash N, Shabsovich D, Garcia L, Damron L, Pantuck AJ, Drakaki A: Frontiers in Systemic Therapy for Unresectable or Metastatic Adrenocortical Carcinoma: Harnessing Novel Therapeutic Approaches. Clin Med Insights Oncol 2025, 19: 11795549251364042.

- Sharma E, Dahal S, Sharma P, Bhandari A, Gupta V, Amgai B, Dahal S: The Characteristics and Trends in Adrenocortical Carcinoma: A United States Population Based Study. J Clin Med Res 2018, 10(8): 636-640.

- Fassnacht M, Terzolo M, Allolio B, Baudin E, Haak H, Berruti A, Welin S, Schade-Brittinger C, Lacroix A, Jarzab B et al: Combination chemotherapy in advanced adrenocortical carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2012, 366(23): 2189-2197.

- Laganà M, Grisanti S, Ambrosini R, Cosentini D, Abate A, Zamparini M, Ferrari VD, Gianoncelli A, Turla A, Canu L et al: Phase II study of cabazitaxel as second-third line treatment in patients with metastatic adrenocortical carcinoma. ESMO Open 2022, 7(2): 100422.

- Kroiss M, Deutschbein T, Schlötelburg W, Ronchi CL, Neu B, Müller HH, Quinkler M, Hahner S, Heidemeier A, Fassnacht M: Salvage Treatment of Adrenocortical Carcinoma with Trofosfamide. Horm Cancer 2016, 7(3): 211-218.

- Kroiss M, Deutschbein T, Schlötelburg W, Ronchi CL, Hescot S, Körbl D, Megerle F, Beuschlein F, Neu B, Quinkler M et al: Treatment of Refractory Adrenocortical Carcinoma with Thalidomide: Analysis of 27 Patients from the European Network for the Study of Adrenal Tumours Registry. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2019, 127(9): 578-584.

- Zheng S, Cherniack AD, Dewal N, Moffitt RA, Danilova L, Murray BA, Lerario AM, Else T, Knijnenburg TA, Ciriello G et al: Comprehensive Pan-Genomic Characterization of Adrenocortical Carcinoma. Cancer Cell 2016, 29(5): 723-736.

- Lerario AM, Mohan DR: Update on Biology and Genomics of Adrenocortical Carcinomas: Rationale for Emerging Therapies. Endocr Rev 2022, 43(6): 1051-1073.

- Lai G, Liu H: The Characteristics of Tumor Microenvironment Predict Survival and Response to Immunotherapy in Adrenocortical Carcinomas. Cells 2023, 12(5): 755.

- Limaye S, Deshmukh J, Rohatagi N, Prabhash K, Rauthan A, Singh S, Kumar A: Usefulness of Comprehensive Genomic Profiling in Clinical Decision-Making in Oncology: A Systematic Review. J Immunother Precis Oncol 2025, 8(1): 55-63.

- Sun-Zhang A, Juhlin CC, Carling T, Scholl U, Schott M, Larsson C, Bajalica-Lagercrantz S: Comprehensive genomic analysis of adrenocortical carcinoma reveals genetic profiles associated with patient survival. ESMO Open 2024, 9(7): 103617.

- Ghosh C, Hu J, Kebebew E: Advances in translational research of the rare cancer type adrenocortical carcinoma. Nat Rev Cancer 2023, 23(12): 805-824.

- Angelousi A, Kyriakopoulos G, Nasiri-Ansari N, Karageorgou M, Kassi E: The role of epithelial growth factors and insulin growth factors in the adrenal neoplasms. Ann Transl Med 2018, 6(12): 253.

- Borges KS, Pignatti E: Wnt/β-catenin activation cooperates with loss of p53 to cause adrenocortical carcinoma in mice. Oncogene 2020, 39(30): 5282-5291.

- Little DW, 3rd, Dumontet T, LaPensee CR, Hammer GD: β-catenin in adrenal zonation and disease. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2021, 522: 111120.

- Chukkalore D, MacDougall K, Master V, Bilen MA, Nazha B: Adrenocortical Carcinomas: Molecular Pathogenesis, Treatment Options, and Emerging Immunotherapy and Targeted Therapy Approaches. Oncologist 2024, 29(9): 738-746.

- Lefol C, Sohier E, Baudet C, Naïbo P, Ruano E, Grand-Masson C, Viari A, Wang Q: Acquired somatic MMR deficiency is a major cause of MSI tumor in patients suspected for "Lynch-like syndrome" including young patients. Eur J Hum Genet 2021, 29(3): 482-488.

- Sun H, Chen G, Guo B, Lv S, Yuan G: Potential clinical treatment prospects behind the molecular mechanism of alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT). J Cancer 2023, 14(3): 417-433.

- Sung JY, Cheong JH: Pan-Cancer Analysis of Clinical Relevance via Telomere Maintenance Mechanism. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22(20): 11101.

- Suh I, Weng J, Fernandez-Ranvier G, Shen WT, Duh QY, Clark OH, Kebebew E: Antineoplastic effects of decitabine, an inhibitor of DNA promoter methylation, in adrenocortical carcinoma cells. Arch Surg 2010, 145(3): 226-232.

- Malarkey M, Toscano AP, Bagheri MH, Solomon J, Machado LB, LoRusso P, Chen A, Folio LR, Goncalves PH: A pilot study of volumetric and density tumor analysis of ACC patients treated with vorinostat in a phase II clinical trial. Heliyon 2023, 9(8): e18680.

- Huang Y, Zhang W, Cui N, Xiao Z, Zhao W, Wang R, Giesy JP, Su X: Fluorene-9-bisphenol regulates steroidogenic hormone synthesis in H295R cells through the AC/cAMP/PKA signaling pathway. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2022, 243: 113982.

- Rizk-Rabin M, Chaoui-Ibadioune S, Vaczlavik A, Ribes C, Polak M, Ragazzon B, Bertherat J: Link between steroidogenesis, the cell cycle, and PKA in adrenocortical tumor cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2020, 500: 110636.

- Lai G, Liu H: The Characteristics of Tumor Microenvironment Predict Survival and Response to Immunotherapy in Adrenocortical Carcinomas. Cells 2023, 12(5): 755.

- Shi X, Liu Y, Cheng S, Hu H, Zhang J, Wei M, Zhao L, Xin S: Cancer Stemness Associated With Prognosis and the Efficacy of Immunotherapy in Adrenocortical Carcinoma. Front Oncol 2021, 11: 651622.

- Raymond VM, Everett JN, Furtado LV, Gustafson SL, Jungbluth CR, Gruber SB, Hammer GD, Stoffel EM, Greenson JK, Giordano TJ et al: Adrenocortical carcinoma is a lynch syndrome-associated cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013, 31(24): 3012-3018.

- Xu F, Guan Y, Zhang P, Xue L, Ma Y, Gao M, Chong T, Ren BC: Tumor mutational burden presents limiting effects on predicting the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors and prognostic assessment in adrenocortical carcinoma. BMC Endocr Disord 2022, 22(1): 130.

- Coutinho AE, Chapman KE: The anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects of glucocorticoids, recent developments and mechanistic insights. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2011, 335(1): 2-13.

- Landwehr LS, Altieri B: Interplay between glucocorticoids and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes on the prognosis of adrenocortical carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer 2020, 8(1): e000469.

- Carneiro BA, Konda B, Costa RB, Costa RLB, Sagar V, Gursel DB, Kirschner LS, Chae YK, Abdulkadir SA, Rademaker A et al: Nivolumab in Metastatic Adrenocortical Carcinoma: Results of a Phase 2 Trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019, 104(12): 6193-6200.

- Habra MA, Stephen B, Campbell M, Hess K, Tapia C, Xu M, Rodon Ahnert J, Jimenez C, Lee JE, Perrier ND et al: Phase II clinical trial of pembrolizumab efficacy and safety in advanced adrenocortical carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer 2019, 7(1): 253.

- Klein O, Senko C, Carlino MS, Markman B, Jackett L, Gao B, Lum C, Kee D, Behren A, Palmer J et al: Combination immunotherapy with ipilimumab and nivolumab in patients with advanced adrenocortical carcinoma: a subgroup analysis of CA209-538. Oncoimmunology 2021, 10(1): 1908771.

- O'Sullivan C, Edgerly M, Velarde M, Wilkerson J, Venkatesan AM, Pittaluga S, Yang SX, Nguyen D, Balasubramaniam S, Fojo T: The VEGF inhibitor axitinib has limited effectiveness as a therapy for adrenocortical cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014, 99(4): 1291-1297.

- Zhang F, Lin H, Cao K, Wang H, Pan J, Zhuang J, Chen X, Huang B, Wang D, Qiu S: Vasculogenic mimicry plays an important role in adrenocortical carcinoma. Int J Urol 2016, 23(5): 371-377.

- Pereira SS, Oliveira S, Monteiro MP: Angiogenesis in the Normal Adrenal Fetal Cortex and Adrenocortical Tumors. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13(5): 1030.

- Kroiss M, Quinkler M, Johanssen S, van Erp NP, Lankheet N, Pöllinger A, Laubner K, Strasburger CJ, Hahner S, Müller HH et al: Sunitinib in refractory adrenocortical carcinoma: a phase II, single-arm, open-label trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012, 97(10): 3495-3503.

- Barlaskar FM, Spalding AC, Heaton JH, Kuick R, Kim AC, Thomas DG, Giordano TJ, Ben-Josef E, Hammer GD: Preclinical targeting of the type I insulin-like growth factor receptor in adrenocortical carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009, 94(1): 204-212.

- Haluska P, Worden F, Olmos D, Yin D, Schteingart D, Batzel GN, Paccagnella ML, de Bono JS, Gualberto A, Hammer GD: Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of the anti-IGF-1R monoclonal antibody figitumumab in patients with refractory adrenocortical carcinoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2010, 65(4): 765-773.

- Naing A, Lorusso P, Fu S, Hong D, Chen HX, Doyle LA, Phan AT, Habra MA, Kurzrock R: Insulin growth factor receptor (IGF-1R) antibody cixutumumab combined with the mTOR inhibitor temsirolimus in patients with metastatic adrenocortical carcinoma. Br J Cancer 2013, 108(4): 826-830.

- Lerario AM, Worden FP, Ramm CA, Hesseltine EA, Stadler WM, Else T, Shah MH, Agamah E, Rao K, Hammer GD: The combination of insulin-like growth factor receptor 1 (IGF1R) antibody cixutumumab and mitotane as a first-line therapy for patients with recurrent/metastatic adrenocortical carcinoma: a multi-institutional NCI-sponsored trial. Horm Cancer 2014, 5(4): 232-239.

- Fassnacht M, Berruti A, Baudin E, Demeure MJ, Gilbert J, Haak H, Kroiss M, Quinn DI, Hesseltine E, Ronchi CL et al: Linsitinib (OSI-906) versus placebo for patients with locally advanced or metastatic adrenocortical carcinoma: a double-blind, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 2015, 16(4): 426-435.

- Hong DS, Postow M: Eganelisib, a First-in-Class PI3Kγ Inhibitor, in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors: Results of the Phase 1/1b MARIO-1 Trial. Clin Cancer Res 2023, 29(12): 2210-2219.

- Berruti A, Sperone P, Ferrero A, Germano A, Ardito A, Priola AM, De Francia S, Volante M, Daffara F, Generali D et al: Phase II study of weekly paclitaxel and sorafenib as second/third-line therapy in patients with adrenocortical carcinoma. Eur J Endocrinol 2012, 166(3): 451-458.

- Pereira SS, Oliveira S, Monteiro MP: Angiogenesis in the Normal Adrenal Fetal Cortex and Adrenocortical Tumors. 2021, 13(5): 1030.

- Kroiss M, Megerle F, Kurlbaum M, Zimmermann S, Wendler J, Jimenez C, Lapa C, Quinkler M, Scherf-Clavel O, Habra MA et al: Objective Response and Prolonged Disease Control of Advanced Adrenocortical Carcinoma with Cabozantinib. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020, 105(5): 1461-1468.

- Campbell MT, Balderrama-Brondani V, Jimenez C, Tamsen G, Marcal LP, Varghese J, Shah AY, Long JP, Zhang M, Ochieng J et al: Cabozantinib monotherapy for advanced adrenocortical carcinoma: a single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2024, 25(5): 649-657.

- Xu L, Qi Y, Xu Y, Lian J, Wang X, Ning G, Wang W, Zhu Y: Co-inhibition of EGFR and IGF1R synergistically impacts therapeutically on adrenocortical carcinoma. Oncotarget 2016, 7(24): 36235-36246.

- Ferruzzi P, Ceni E, Tarocchi M, Grappone C, Milani S, Galli A, Fiorelli G, Serio M, Mannelli M: Thiazolidinediones inhibit growth and invasiveness of the human adrenocortical cancer cell line H295R. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005, 90(3): 1332-1339.

- Luconi M, Mangoni M, Gelmini S, Poli G, Nesi G, Francalanci M, Pratesi N, Cantini G, Lombardi A, Pepi M et al: Rosiglitazone impairs proliferation of human adrenocortical cancer: preclinical study in a xenograft mouse model. Endocr Relat Cancer 2010, 17(1): 169-177.

- Cantini G, Fei L, Canu L: Stimulated Expression of CXCL12 in Adrenocortical Carcinoma by the PPARgamma Ligand Rosiglitazone Impairs Cancer Progression. J Pers Med 2021, 11(11): 1097.

- Hui W, Liu S: Nutlin-3a as a novel anticancer agent for adrenocortical carcinoma with CTNNB1 mutation. Cancer Med 2018, 7(4): 1440-1449.

- Bussey KJ, Bapat A, Linnehan C, Wandoloski M, Dastrup E, Rogers E, Gonzales P, Demeure MJ: Targeting polo-like kinase 1, a regulator of p53, in the treatment of adrenocortical carcinoma. Clin Transl Med 2016, 5(1): 1.

- Lin RC, Chao YY, Lien WC, Chang HC, Tsai SW, Wang CY: Polo‑like kinase 1 selective inhibitor BI2536 (dihydropteridinone) disrupts centrosome homeostasis via ATM‑ERK cascade in adrenocortical carcinoma. Oncol Rep 2023, 50(3): 167.

- Hadjadj D, Kim SJ, Denecker T, Ben Driss L, Cadoret JC, Maric C, Baldacci G, Fauchereau F: A hypothesis-driven approach identifies CDK4 and CDK6 inhibitors as candidate drugs for treatments of adrenocortical carcinomas. Aging (Albany NY) 2017, 9(12): 2695-2716.

- Le Tourneau C, Hoimes C, Zarwan C, Wong DJ, Bauer S, Claus R, Wermke M, Hariharan S, von Heydebreck A, Kasturi V et al: Avelumab in patients with previously treated metastatic adrenocortical carcinoma: phase 1b results from the JAVELIN solid tumor trial. J Immunother Cancer 2018, 6(1): 111.

- Raj N, Zheng Y, Kelly V, Katz SS, Chou J, Do RKG, Capanu M, Zamarin D, Saltz LB, Ariyan CE et al: PD-1 Blockade in Advanced Adrenocortical Carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2020, 38(1): 71-80.

- Capdevila J, Hernando J: Cabozantinib plus Atezolizumab in Advanced, Progressive Endocrine Malignancies: A Multicohort, Basket, Phase II Trial (CABATEN/GETNE-T1914). Clin Cancer Res 2025, 31(22): 4655-4663.

- Zhu YC, Wei ZG, Wang JJ, Pei YY, Jin J, Li D, Li ZH, Liu ZR, Min Y, Li RD et al: Camrelizumab plus apatinib for previously treated advanced adrenocortical carcinoma: a single-arm phase 2 trial. Nat Commun 2024, 15(1): 10371.

- Liu-Chittenden Y, Jain M, Kumar P, Patel D, Aufforth R, Neychev V, Sadowski S, Gara SK, Joshi BH, Cottle-Delisle C et al: Phase I trial of systemic intravenous infusion of interleukin-13-Pseudomonas exotoxin in patients with metastatic adrenocortical carcinoma. Cancer Med 2015, 4(7): 1060-1068.

- Knudson KM, Hwang S, McCann MS, Joshi BH, Husain SR, Puri RK: Recent Advances in IL-13Rα2-Directed Cancer Immunotherapy. Front Immunol 2022, 13: 878365.

- Pivonello R, Bancos I, Feelders RA, Kargi AY, Kerr JM, Gordon MB, Mariash CN, Terzolo M, Ellison N, Moraitis AG: Relacorilant, a Selective Glucocorticoid Receptor Modulator, Induces Clinical Improvements in Patients With Cushing Syndrome: Results From A Prospective, Open-Label Phase 2 Study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021, 12: 662865.

- Munster PN, Greenstein AE: Overcoming Taxane Resistance: Preclinical and Phase 1 Studies of Relacorilant, a Selective Glucocorticoid Receptor Modulator, with Nab-Paclitaxel in Solid Tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2022, 28(15): 3214-3224.

- Colombo N, Van Gorp T: Relacorilant + Nab-Paclitaxel in Patients With Recurrent, Platinum-Resistant Ovarian Cancer: A Three-Arm, Randomized, Controlled, Open-Label Phase II Study. J Clin Oncol 2023, 41(30): 4779-4789.

- Hahner S, Kreissl MC, Fassnacht M, Haenscheid H, Knoedler P, Lang K, Buck AK, Reiners C, Allolio B, Schirbel A: [131I]iodometomidate for targeted radionuclide therapy of advanced adrenocortical carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012, 97(3): 914-922.

- Hahner S, Hartrampf PE: Targeting 11-Beta Hydroxylase With [131I]IMAZA: A Novel Approach for the Treatment of Advanced Adrenocortical Carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2022, 107(4): e1348-e1355.

- Grisanti S, Filice A, Basile V, Cosentini D, Rapa I, Albano D, Morandi A, Laganà M, Dalla Volta A, Bertagna F et al: Treatment With 90Y/177Lu-DOTATOC in Patients With Metastatic Adrenocortical Carcinoma Expressing Somatostatin Receptors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020, 105(3): dgz091.

- Zhou M, Huang Z, Ma Z, Chen J, Lin S, Yang X, Gong Q, Braunstein Z, Wei Y, Rao X et al: The next frontier in antibody-drug conjugates: challenges and opportunities in cancer and autoimmune therapy. Cancer Drug Resist 2025, 8: 34.

- Lemech C, Woodward N, Chan N, Mortimer J, Naumovski L, Nuthalapati S, Tong B, Jiang F, Ansell P, Ratajczak CK et al: A first-in-human, phase 1, dose-escalation study of ABBV-176, an antibody-drug conjugate targeting the prolactin receptor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Invest New Drugs 2020, 38(6): 1815-1825.

- Sun N-Y, Kumar S, Weiner A, Kim YS, Mendoza A, Nguyen R, Okada R, Pommier Y, Martinez D, Pogoriler J et al: Abstract 6573: Targeting DLK1, a Notch ligand, with an antibody-drug conjugate in adrenocortical carcinoma. Cancer Res 2024, 84(6_Supplement): 6573-6573.

- Zammarchi F, Havenith K, Leatherdale B, Roberts B, Montolio L, Patel A, Janghra N, Alves P, Zaitseva K, Oblette C et al: Abstract 1604: Preclinical development of ADCT-211, a novel pyrrolobenzodiazepine dimer-based antibody-drug conjugate targeting solid tumors expressing IL13RA2. Cancer Res 2023, 83(7_Supplement): 1604-1604.

- Baudin E, Jimenez C, Fassnacht M, Grisanti S, Menke CW, Haak H, Subbiah V, Capdevila J, Fouchardiere CDL, Granberg D et al: EO2401, a novel microbiome-derived therapeutic vaccine for patients with adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC): Preliminary results of the SPENCER study. J Clin Oncol 2022, 40(16_suppl): 4596-4596.

- Epperly R, Pinto EM, Santiago T, Sheppard H, Clay MR, Morton C, Nguyen P, Zhou Y, Woolard M, O'Reilly C et al: Abstract 1197: B7-H3-CAR T cells for the treatment of pediatric adrenocortical carcinoma. Cancer Res 2023, 83(7_Supplement): 1197-1197.

- Zhou M, Tian M, Li C: Copper-Based Nanomaterials for Cancer Imaging and Therapy. Bioconjug Chem 2016, 27(5): 1188-1199.

- Xu Y, Zeng Y, Xiao X, Liu H, Zhou B, Luo B, Saw PE, Jiang Q: Targeted Imaging of Tumor Associated Macrophages in Breast Cancer. BIO Integration 2023, 4(3): 114-124.

- Guo Z, Saw PE, Jon S: Non-Invasive Physical Stimulation to Modulate the Tumor Microenvironment: Unveiling a New Frontier in Cancer Therapy. BIO Integration 2024, 5(1): 1-14.

- Cheng CH, Shi SS: Artificial intelligence in cancer: applications, challenges, and future perspectives. Mol Cancer 2025, 24(1): 274.

- Sharma A, Lysenko A, Jia S, Boroevich KA: Advances in AI and machine learning for predictive medicine. J Hum Genet 2024, 69(10): 487-497.

- Aravazhi PS, Gunasekaran P, Benjamin NZY, Thai A, Chandrasekar KK, Kolanu ND, Prajjwal P, Tekuru Y, Brito LV, Inban P: The integration of artificial intelligence into clinical medicine: Trends, challenges, and future directions. Dis Mon 2025, 71(6): 101882.

- Smith DC, Kroiss M, Kebebew E, Habra MA, Chugh R, Schneider BJ, Fassnacht M, Jafarinasabian P, Ijzerman MM, Lin VH et al: A phase 1 study of nevanimibe HCl, a novel adrenal-specific sterol O-acyltransferase 1 (SOAT1) inhibitor, in adrenocortical carcinoma. Invest New Drugs 2020, 38(5): 1421-1429.

Annals of urologic oncology

p-ISSN: 2617-7765, e-ISSN: 2617-7773

Copyright © Ann Urol Oncol. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License.

Copyright © Ann Urol Oncol. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License.

Submit Manuscript

Submit Manuscript