Review Article | Open Access

Testicular Carcinoma: Molecular Pathogenesis, Diagnostic Advances, and Evolving Therapeutic Strategies

Aadhira Aiyar1, Alina Roos11Department of Health Sciences, Tallinn Health Care College, Kännu Road 67, Tallinn, 13418, Estonia.

Correspondence: Aadhira Aiyar (Department of Health Sciences, Tallinn Health Care College, Kännu Road 67, Tallinn, 13418, Estonia; Email: a.aiyar911@outlook.com).

Annals of Urologic Oncology 2025, 8(4): 167-176. https://doi.org/10.32948/auo.2025.11.29

Received: 30 Sep 2025 | Accepted: 28 Oct 2025 | Published online: 30 Nov 2025

Key words testicular carcinoma, germ cell tumors, molecular pathogenesis, biomarkers, mir-371a-3p, precision diagnostics, targeted therapy, immune-oncology

The majority of testicular carcinoma develops from germinoma neoplasia in situ (GCNIS), a precursor lesion reflecting perturbed embryonic germ cell differentiation [3]. The germ cell developmental biology, with its robust pluripotency, epigenetic plasticity and sensitivity to hormonal and environmental influences are instrumental in tumor initiation [4]. Consistent genetic changes and anomalies have been recapitulated at the level of protein mutations in testicular germ cell tumors (TGCTs), namely, i(12p), KIT and its ligand (KITLG) mutations as well as the Wnt/β-catenin and PI3K/AKT pathways activation [5]. This discovery clarifies the lineage of both seminomatous and non-seminomatous histology highlighting the heterogeneous nature of TGCTs that will likely have important implications for therapeutic response, and clinical outcomes [3].

The diagnostic terrain for testicular cancer has developed greatly in parallel with the molecular knowledge [2]. Historically, diagnosis was made based on physical examination findings along with scrotal ultrasound and serum tumor markers including b-HCG, LDH, and AFP [6]. However, sensitiveness and specification of these markers are poor and then they have driven the search for a better non-invasive marker [7]. Novel approaches, such as circulating tumor DNA and blood-based microRNA miR-371a-3p, have shown excellent diagnostic performance exceeding that of conventional markers for the diagnosis of recurrent disease, treatment monitoring, and active cancer detection [8]. Intermittent and irregular clinical biomarkers have largely enabled personalized disease monitoring [9]. In addition, imaging techniques represented by CT, MRI and PET are useful for staging and post-treatment residual disease evaluation or choosing the treatment options; in turn, high-resolution ultrasound has also made early detection of testicular masses possible [10]. More recently, research on radiomics and the application of artificial intelligence (AI) has been used to improve diagnostic accuracy by revealing subtle imaging patterns related to tumor biology, risk of recurrence or response to systemic therapy [11]. Testicular carcinoma is still one of the success stories in oncology with curative treatment. The mid-late 20th century administration of cisplatin-containing chemotherapy led to a dramatic increase in survival, including at the metastatic stage [12]. Current treatment strategies, comprising risk-adapted chemotherapy (e.g., Single agents based on the BEP regimen), targeted radiation and radical inguinal orchiectomy. show optimal cure rates [13]. Nevertheless, considerations concerning side-effects especially long-term sequelae like infertility, metabolic disorders, cardiovascular diseases or secondary cancers have stimulated an increased interest to optimize treatment concepts [14]. It is in this field that new strategies, such as molecular targeted agents, immune checkpoint inhibitors and reduced-intensity or watch-and-wait approach, seek to achieve a combination of curative potential and long-term survival. Fertility preservation and psychosocial care are some of the cornerstones of care, especially given that most patients are very young [15]. These new treatments including sperm banking, and testicular tissue preservation, as well as new developments in IUI provides novel strategies for the preservation of reproductive capacity.

We summarize existing data on the molecular pathogenesis of testicular carcinoma, recent advances in diagnosis and treatment. To this end, combining new advances in tumor biology, biomarker science, imaging and new precision oncology approaches aimed at more precisely tailoring treatment to each patient’s individual risk profile we hope to provide a full spectrum overview of the disease and emergent strategies towards increasing cure rates and reducing long term toxicities. This review highlights the need for a multidisciplinary, patient-centered approach as testicular carcinoma treatment moves forward from its era of personalized medicine.

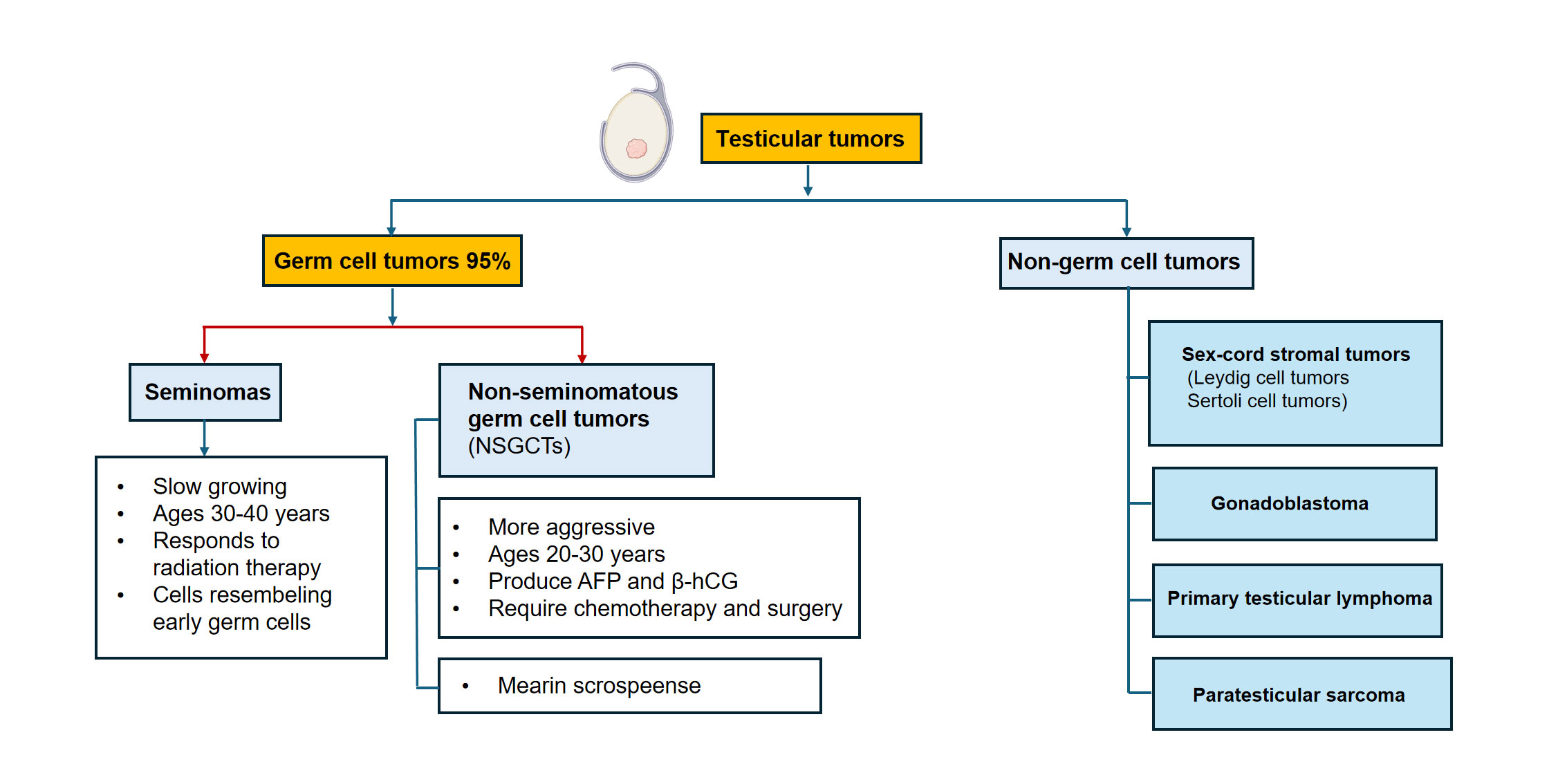

Seminomas originate from GCNIS and resemble primordial germ cells. Presentation is common at age 30-40 years, with a slow growth and radio-sensitivity of these tumors [19]. Seminomas usually present with homogeneous, well-circumscribed hypoechoic masses on US. From the molecular point of view, some of these cells often show expression of OCT3/4, SOX17, PLAP, CD117 (KIT), indicating the retention of their germ cell phenotype (Damjanov 2021). Despite their radiosensitivity, seminomas have an excellent prognosis with a cure rate of over 95%, even in the context of metastatic disease [20].

NSGCTs, however, primarily occur in younger men (20–30-year-old males) and are more biologically aggressive [21]. This category includes embryonal carcinoma, YST, choriocarcinoma, teratoma and mixed germ cell tumors representing two or more histological types [3]. Most of NSGCTs secrete tumor markers into the blood, including alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (b-hCG), so multimodal treatment such as chemotherapy plus surgery is required [7]. They are heterogeneous and differentiate to become part of the embryonic (embryonal carcinoma), yolk sac, chorionic (choriocarcinoma) or somatic teratoma lineages [3].

Non-germ cell neoplasms and are very uncommon yet have serious diagnostic as well as therapeutic implications (1994). Sex-cord stromal tumors are usually benign but can cause metastasis in rare occasions, including Leydig cell tumor and Sertoli cell tumor [22]. Steroid production may give rise to hormonal effects, such as gynecomastia and precocious puberty [23]. Rare para-testicular tumors include gonadoblastoma (a tumor of the genital ridge associated with chromosomal anomalies e.g. gonadal dysgenesis), primary testicular lymphoma (the most common testicular malignancy in older men), and supportive soft tissue sarcomas originating from the scrotal wall [16].

To guide the treatment decision-making, it is important to determine accurately what kind of classification it is. Seminomas and NSGCT show striking differences in the treatment sensitivity, with seminomas responding well to radiotherapy but patients with sinonasal anal plastic carcinoma (SNAC) patients get treated with chemotherapy and other material surgery cases at least one adjuvant therapy [24]. For mixed tumors, surgery must be directed towards most the aggressive component. The advent of molecular profiling is further shaping this classification by providing information on treatment response and relapse risk. The International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group (IGCCCG) system categorizes metastatic germ cell tumors into 3 risk categories-low, intermediate, and poor-based on tumor markers and sites of metastases. This is the framework upon which chemotherapy intensity and long-term survival estimates are based. A comparative schematic of seminoma and NSGCT histology is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The histologic and clinicopathologic spectrum of testicular tumor. An illustration for seminoma and NSGCT. The seminoma panel shows a homogenous, well-circumscribed mass while the NSGCT panel exhibits a heterogeneous mass containing areas of hemorrhage and necrosis reflecting its aggressive mixed histology.

Figure 1. The histologic and clinicopathologic spectrum of testicular tumor. An illustration for seminoma and NSGCT. The seminoma panel shows a homogenous, well-circumscribed mass while the NSGCT panel exhibits a heterogeneous mass containing areas of hemorrhage and necrosis reflecting its aggressive mixed histology.

This deviation is the consequence of duplication of the short arm of chromosome 12, which results in an overexpression of genes involved in cell proliferation and stemness (such as KRAS, CCND2, NANOG and BCAT1) [30]. The initial stimuli leading to the development of i(12p) are largely unknown but represent a key transition between GCNIS and invasive cancer [31]. Gains of chromosomes 7, 8 and 21, and losses of chromosome 11 and 13-Are additional events contributing to treatment resistance. The relatively low somatic mutation burden in TGCTs as compared with other adult cancers indicates that oncogenic process is mainly mediated by chromosomal and epigenetic changes [32]. Epigenetic control is a main contributor to explaining the differential biological behavior of seminomas and NSGCTs. Seminomas display a globally undermethylated DNA profile much like the pattern demonstrated by PGCs, which correspond to their higher degree of undifferentiation. In contrast, NSGCTs present with increased DNA methylation and unique histone modifications that reflect differentiation into EC, YST, choriocarcinoma (CH), or teratoma [33]. The extent to which these epigenetic differences contribute to tumor biology is demonstrated by the phenotypic differences between tumors: while seminomas generally grow slowly and are radiosensitive, NSGCTs proliferate quickly with a degree of lineage heterogeneity showing differential sensitivities to treatment [32]. Continued activity of OCT3/4-, NANOG-, LIN28- and other stemness factor-regulated transcriptional networks drives tumorigenesis by promoting the retention of embryonic-like features [34]. Several important signaling pathways are involved in the process of development and progress of TGCT [5]. Alterations in KIT/KITLG pathway (such as c-KIT alterations and KITLG amplification) will have brought about the survival and proliferation advantage of GCPs, which are prevailing in seminomas [35]. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is frequently activated in seminomatous and non-seminomatous tumors enabling growth, metabolic adaption, and resistance to apoptosis [36]. Activation of the RAS/MAPK signaling pathway - often through KRAS activation or 12p amplification - enhances cell proliferation and has also been identified as a driver of invasiveness [37]. In addition, the increased expression of Wnt/β-catenin pathway in NSGCT s helps for the differentiation to embryonal carcinoma and teratomatous component [38]. The TME plays a large role in the biology of TGCT. Seminomas are frequently associated with marked lymphocytic infiltration, in which the activated Th1- and Ts-type T-cells could contribute to radiosensitivity. In contrast, NSGCTs usually present with a more immunosuppressive microenvironment, marked by the presence of tumor-associated macrophages [39]. Disparate expression of immune checkpoint molecules, such as PD-1 and PD-L1 reflects opportunities for development of immunotherapeutic measures in the future although their therapeutic application to the clinic is currently being worked on. Although originating from GCNIS, seminomas and NSGCTs show extensive dissimilarity in terms of their molecular and biological characteristics.

Seminomas are associated with a hypomethylated epigenetic profile, express both SOX17 and KIT, and present as relatively undifferentiated, which renders them highly sensitive to radiation and chemotherapy [40]. In contrast, NSGCTs are hypermethylated and express SOX2 and SALL4, suggesting they have a complex differentiation pattern that may warrant aggressive multimodal therapy [33]. These differences underlie modern risk stratification and therapeutic decision making. Recent multi-omics studies have improved our understanding of TGCT biology. Genomic studies show a low mutational load, with recurrent chromosomal gains and losses. Transcriptomic studies reveal high expression levels of pluripotency-related genes in seminomas, and lineage specific signatures in NSGCTs [41]. Proteome-based studies could reveal essential biomarkers, in particular microRNA miR-371a-3p, having high potential for the diagnosis and follow-up of the disease. Metabolomic profiling uncovers that seminomas are dependent on glycolysis, whereas NSGCTs are more oxidative in metabolism due to their distinct energy demands and differentiation status [42]. Together, these multi-omics results support the development of personalized tools for diagnosis and therapy to one step closer toward precision oncology in testicular cancer. Key molecular pathways in TGCT pathogenesis are illustrated in Figure 2. A summary of the distinguishing features between seminomas and NSGCTs is provided in Table 1.

Figure 2. The cellular and molecular pathogenesis of TGCT. Schematic summarizing the process from a PGC to GCNIS and separate line of development towards either seminoma or non-seminomatous germ cell tumors (NSGCT). Various molecular fingerprints are mentioned, such as gains of i(12p), dysregulation of signaling pathways (KIT, PI3K/AKT and Wnt/β-catenin) or the differences in the epigenetic landscapes with global hypomethylation in seminoma versus hypermethylation in NSGCT.

Figure 2. The cellular and molecular pathogenesis of TGCT. Schematic summarizing the process from a PGC to GCNIS and separate line of development towards either seminoma or non-seminomatous germ cell tumors (NSGCT). Various molecular fingerprints are mentioned, such as gains of i(12p), dysregulation of signaling pathways (KIT, PI3K/AKT and Wnt/β-catenin) or the differences in the epigenetic landscapes with global hypomethylation in seminoma versus hypermethylation in NSGCT.

|

Table 1. Comparison of testicular germ cell tumors: seminoma vs NSGCT. |

|||

|

Feature |

Seminoma |

Non-Seminomatous germ cell tumor (NSGCT) |

Clinical / Pathological significance |

|

Epigenetics |

Hypomethylated |

Hypermethylated |

Seminomas: simpler epigenetic profile; NSGCTs: more complex |

|

Markers |

OCT3/4, SOX17, KIT |

OCT3/4, SOX2, SALL4 |

Useful for immunohistochemistry diagnosis |

|

Biology |

Less differentiated |

Highly heterogeneous |

NSGCTs: mixed histology; Seminomas: more uniform |

|

Treatment sensitivity |

Radio- and chemosensitive |

May require aggressive multimodal therapy |

Seminomas: respond well to radiotherapy; NSGCTs: need combo therapy |

|

Age of onset |

30–40 years |

20–30 years |

Younger patients more often have NSGCT |

|

Histology |

Uniform, sheets of cells |

Mixed: embryonal carcinoma, yolk sac, choriocarcinoma, teratoma |

Guides pathologic diagnosis |

|

Metastatic pattern |

Lymph nodes primarily |

Lymphatic and hematogenous spread |

NSGCTs: lungs, liver, brain |

|

Tumor growth rate |

Slow-growing |

Rapid-growing |

NSGCTs can progress quickly |

|

Prognosis |

Generally excellent |

Variable; depends on subtype and stage |

Seminomas: very high cure rates |

|

Serum tumor markers |

Usually none or mild β-hCG elevation |

AFP, β-hCG, LDH may be elevated |

Useful for diagnosis and monitoring |

|

Molecular alterations |

KIT mutations common |

TP53, KRAS, diverse mutations |

Can influence targeted therapy research |

|

Histological variants |

Classic, spermatocytic |

Embryonal carcinoma, teratoma, yolk sac tumor, choriocarcinoma |

Helps with subtype-specific management |

|

Key Clinical Features |

Painless testicular mass, slow progression |

Rapidly enlarging testicular mass, sometimes with symptoms from metastases |

Guides clinical suspicion and workup |

|

Abbreviations: NSGCT, non-seminomatous germ cell tumor; AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; β-hCG, beta-human chorionic gonadotropin; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase. |

|||

Recent findings from multi-omics research and immunological profiling are informing the creation of personalised therapeutic approaches. Research is ongoing into immune checkpoint inhibitors and targeted therapies aimed at specific molecular alterations, including KIT or RAS/MAPK pathway mutations, to enhance outcomes in high-risk non-seminomatous germ cell tumors (NSGCTs) and to mitigate treatment-related toxicity in seminomas [48]. The integration of molecular knowledge with clinical and histopathological data facilitates accurate risk assessment, personalised therapy, and enhanced survival outcomes in patients with testicular germ cell tumors.

|

Table 2. Clinical management and prognosis of seminomas vs NSGCTs. |

||

|

Clinical feature |

Seminoma profile |

NSGCT Profile |

|

Typical presentation |

Painless testicular mass, slow-growing |

Rapidly enlarging mass, sometimes symptomatic metastases |

|

Serum tumor markers |

Usually none or mild β-hCG elevation |

AFP, β-hCG, LDH often elevated |

|

Initial management |

Radical inguinal orchiectomy |

Radical inguinal orchiectomy |

|

Adjuvant therapy |

Radiotherapy for stage I–II in selected cases; chemotherapy if higher stage |

Chemotherapy (BEP: bleomycin, etoposide, cisplatin) for stage II–III; surgery for residual masses |

|

Chemotherapy sensitivity |

High (cisplatin-based) |

Variable; often requires aggressive multimodal therapy |

|

Radiotherapy sensitivity |

Highly sensitive |

Generally resistant |

|

Prognosis |

Excellent; >95% cure in early-stage disease |

Good overall, dependent on subtype and stage; higher relapse risk in aggressive variants |

|

Metastatic pattern |

Lymph nodes primarily |

Lymphatic and hematogenous (lungs, liver, brain) |

|

Surveillance |

Serial imaging, serum markers; follow-up for 5–10 years depending on stage |

Intensive surveillance post-chemotherapy; imaging and serum markers for at least 5 years; longer in high-risk cases |

|

Recurrence risk |

Low; typically late if it occurs |

Higher; often early, especially in high-risk NSGCTs |

|

Emerging therapies |

Targeted therapies and immunotherapy under study; currently mainly standard chemo/radiotherapy |

Targeted therapies (KIT, RAS/MAPK) and immune checkpoint inhibitors under investigation |

|

Abbreviations: NSGCT, non-seminomatous germ cell tumor; BEP, bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin; AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; β-hCG, beta-human chorionic gonadotropin; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase. |

||

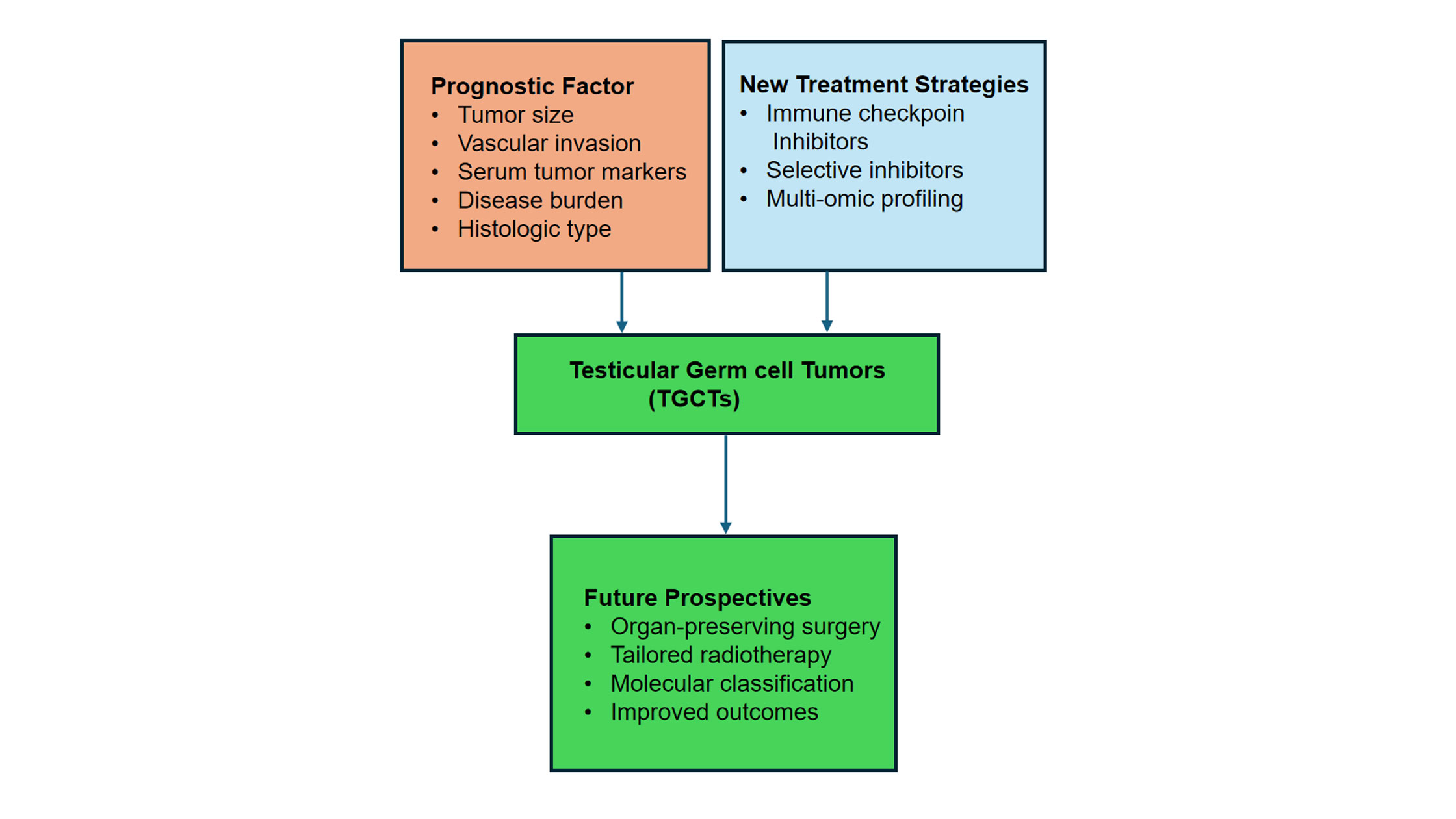

Figure 3. Next steps in TGCT care and precision medicine model. This figure provides an overview of the main factors that determine prognosis, new treatment approaches, and potential clinical paths for testicular germ cell tumours (TGCTs). It emphasises how risk assessment and treatment customisation are changing because of molecular profiling, targeted agents, and immunotherapy. Multi-omics biomarkers like miR-371a-3p should be included to enhance early identification and enhance patient outcomes.

Figure 3. Next steps in TGCT care and precision medicine model. This figure provides an overview of the main factors that determine prognosis, new treatment approaches, and potential clinical paths for testicular germ cell tumours (TGCTs). It emphasises how risk assessment and treatment customisation are changing because of molecular profiling, targeted agents, and immunotherapy. Multi-omics biomarkers like miR-371a-3p should be included to enhance early identification and enhance patient outcomes.

Molecular features provide insight into TGCT biology. At the same time, multi-omics profiling and circulating biomarkers like miR-371a-3p are improving early diagnosis, assessment of treatment response, and relapse prediction, with implications for both established treatments and novel strategies such as immunotherapy and targeted agents. Comprehensive management should encompass oncologic care, follow-up surveillance, fertility preservation, psychological support, and efforts to minimize treatment-related toxicities. As precision medicine becomes more integrated into TGCT management, personalized, risk-adapted treatment strategies are being implemented to maximize efficacy while minimizing toxicity. In summary, the integration of clinical and molecular data provides a strong foundation for understanding, diagnosing, and treating TGCT. While both major subtypes originate from GCNIS, they are distinct entities in terms of biology, prognosis, and treatment, underscoring the necessity for accurate differentiation. Ongoing progress in molecular biology, multi-omics, and personalized therapy positions TGCT as a paradigm for precision oncology in curable cancers, with the goal of further improving survival and quality of life.

None.

Ethical policy

Non applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this publication.

Author contributions

Aadhira Aiyar and Alina Roos contributed to design of the work, data collection, and drafting the article.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Funding

None.

- Cheng L, Albers P, Berney DM, Feldman DR, Daugaard G, Gilligan T, Looijenga LH: Testicular cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2018, 4(1): 29.

- Sadek KM, AbdEllatief HY, Mahmoud SF, Alexiou A, Papadakis M, Al‐Hajeili M, Saad HM, Batiha GES: New insights on testicular cancer prevalence with novel diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic approaches. Cancer Rep 2024, 7(3): e2052.

- Katabathina VS, Vargas-Zapata D, Monge RA, Nazarullah A, Ganeshan D, Tammisetti V, Prasad SR: Testicular germ cell tumors: classification, pathologic features, imaging findings, and management. Radiographics 2021, 41(6): 1698-1716.

- Oosterhuis JW, Looijenga LH: Human germ cell tumours from a developmental perspective. Nat Rev Cancer 2019, 19(9): 522-537.

- Das M, Kleppa L, Haugen T: Functions of genes related to testicular germ cell tumour development. Andrology 2019, 7(4): 527-535.

- Marroncelli N, Ambrosini G, Errico A, Vinco S, Dalla Pozza E, Cogo G, Cristanini I, Migliorini F, Zampieri N, Dando I: Is Human Chorionic Gonadotropin a Reliable Marker for Testicular Germ Cell Tumor? New Perspectives for a More Accurate Diagnosis. Cancers 2025, 17(14): 2409.

- Murray MJ, Huddart RA, Coleman N: The present and future of serum diagnostic tests for testicular germ cell tumours. Nat Rev Urol 2016, 13(12): 715-725.

- Seales CL, Puri D, Yodkhunnatham N, Pandit K, Yuen K, Murray S, Smitham J, Lafin JT, Bagrodia A: Advancing GCT management: a review of miR-371a-3p and other miRNAs in comparison to traditional serum tumor markers. Cancers 2024, 16(7): 1379.

- Passaro A, Al Bakir M, Hamilton EG, Diehn M, André F, Roy-Chowdhuri S, Mountzios G, Wistuba II, Swanton C, Peters S: Cancer biomarkers: Emerging trends and clinical implications for personalized treatment. Cell 2024, 187(7): 1617-1635.

- Barrisford GW, Kreydin EI, Preston MA, Rodriguez D, Harisighani MG, Feldman AS: Role of imaging in testicular cancer: current and future practice. Future Oncol 2015, 11(18): 2575-2586.

- Bera K, Braman N, Gupta A, Velcheti V, Madabhushi A: Predicting cancer outcomes with radiomics and artificial intelligence in radiology. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2022, 19(2): 132-146.

- Bucher-Johannessen C, Page CM, Haugen TB, Wojewodzic MW, Fosså SD, Grotmol T, Haugnes HS, Rounge TB: Cisplatin treatment of testicular cancer patients introduces long-term changes in the epigenome. Clin Epigenetics 2019, 11(1): 179.

- Raggi D, Chakrabarti D, Cazzaniga W, Aslam R, Miletic M, Gilson C, Holwell R, Champion P, King A, Mayer E et al: Management of Testicular Cancer. JCO Oncol Pract 2025 Epub ahead of print.: OP-25-00211.

- Abouassaly R, Fossa SD, Giwercman A, Kollmannsberger C, Motzer RJ, Schmoll H-J, Sternberg CN: Sequelae of treatment in long-term survivors of testis cancer. Eur Urol 2011, 60(3): 516-526.

- Logan S, Anazodo A: The psychological importance of fertility preservation counseling and support for cancer patients. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 2019, 98(5): 583-597.

- Al-Obaidy KI, Idrees MT: Testicular tumors: a contemporary update on morphologic, immunohistochemical and molecular features. Adv Anat Pathol 2021, 28(4): 258-275.

- Idrees MT, Ulbright TM, Oliva E, Young RH, Montironi R, Egevad L, Berney D, Srigley JR, Epstein JI, Tickoo SK: The World Health Organization 2016 classification of testicular non‐germ cell tumours: A review and update from the International Society of Urological Pathology Testis Consultation Panel. Histopathology 2017, 70(4): 513-521.

- Looijenga LH: Human testicular (non) seminomatous germ cell tumours: the clinical implications of recent pathobiological insights. J Pathol 2009, 218(2): 146-162.

- Coursey Moreno C, Small WC, Camacho JC, Master V, Kokabi N, Lewis M, Hartman M, Mittal PK: Testicular tumors: what radiologists need to know—differential diagnosis, staging, and management. Radiographics 2015, 35(2): 400-415.

- Bumbasirevic U, Zivkovic M, Petrovic M, Coric V, Lisicic N, Bojanic N: Treatment options in stage I seminoma. Oncol Res 2023, 30(3): 117.

- Gillessen S, Sauvé N, Collette L, Daugaard G, de Wit R, Albany C, Tryakin A, Fizazi K, Stahl O, Gietema JA et al: Predicting outcomes in men with metastatic nonseminomatous germ cell tumors (NSGCT): results from the IGCCCG update consortium. J Clin Oncol 2021, 39(14): 1563-1574.

- Young RH: Sex cord-stromal tumors of the ovary and testis: their similarities and differences with consideration of selected problems. Mod Pathol 2005, 18: S81-S98.

- Sansone A, Romanelli F, Sansone M, Lenzi A, Di Luigi L: Gynecomastia and hormones. Endocrine 2017, 55(1): 37-44.

- Gu L, Zhang L, Hou N, Li M, Shen W, Xie X, Teng Y: Clinical and radiographic characterization of primary seminomas and nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. Niger J Clin Pract 2019, 22(3): 342-349.

- Baroni T, Arato I, Mancuso F, Calafiore R, Luca G: On the origin of testicular germ cell tumors: from gonocytes to testicular cancer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019, 10: 343.

- Kristensen DM, Sonne SB, Ottesen AM, Perrett RM, Nielsen JE, Almstrup K, Skakkebaek NE, Leffers H, Rajpert-De Meyts E: Origin of pluripotent germ cell tumours: the role of microenvironment during embryonic development. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2008, 288(1-2): 111-118.

- Ramakrishna NB, Murison K, Miska EA, Leitch HG: Epigenetic regulation during primordial germ cell development and differentiation. Sex Dev 2021, 15(5-6): 411-431.

- Ahmed SF, Armstrong K, Cheng EY, Cools M, Harley V, Mendonca BB, Nordenström A, Rey R, Sandberg DE, Utari A et al: Differences of sex development. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2025, 11(1): 54.

- Yang M, Deng B, Geng L, Li L, Wu X: Pluripotency factor NANOG promotes germ cell maintenance in vitro without triggering dedifferentiation of spermatogonial stem cells. Theriogenology 2020, 148: 68-75.

- Looijenga LH, Zafarana G, Grygalewicz B, Summersgill B, DEBIEC‐RYCHTER M, Veltman J, Schoenmakers EF, Rodriguez S, Jafer O, Clark J et al: Role of gain of 12p in germ cell tumour development. Apmis 2003, 111(1): 161-170.

- Rosta V, Krausz C: Comprehensive analyses of genetic and clinical factors in patients affected by Testicular Germ Cell Tumor. Doctoral dissertation 2022.

- Lobo J, Gillis AJ, Jeronimo C, Henrique R, Looijenga LH: Human germ cell tumors are developmental cancers: impact of epigenetics on pathobiology and clinic. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20(2): 258.

- Nicu A-T, Ionel IP, Stoica I, Burlibasa L, Jinga V: Recent advancements in research on DNA methylation and testicular germ cell tumors: unveiling the intricate relationship. Biomedicines 2024, 12(5): 1041.

- Liu L, Yin S, Brobbey C, Gan W: Ubiquitination in cancer stem cell: roles and targeted cancer therapy. STEMedicine 2020, 1(3): e37.

- Shen H, Shih J, Hollern DP, Wang L, Bowlby R, Tickoo SK, Thorsson V, Mungall AJ, Newton Y, Hegde AM et al: Integrated molecular characterization of testicular germ cell tumors. Cell Rep 2018, 23(11): 3392-3406.

- Barchi M, Bielli P, Dolci S, Rossi P, Grimaldi P: Non-coding RNAs and splicing activity in testicular germ cell tumors. Life 2021, 11(8): 736.

- Xu H, Ren S, Wang Y, Zhang T, Lu J: Abnormal activation of the Ras/MAPK signaling pathway in oncogenesis and progression. Cancer Adv 2025, 8: e25002.

- Dietrich B, Haider S, Meinhardt G, Pollheimer J, Knöfler M: WNT and NOTCH signaling in human trophoblast development and differentiation. Cell Mol Life Sci 2022, 79(6): 292.

- Solinas C, Chanzá NM, Awada A, Scartozzi M: The immune infiltrate in prostate, bladder and testicular tumors: an old friend for new challenges. Cancer Treat Rev 2017, 53: 138-145.

- Brait M, Maldonado L, Begum S, Loyo M, Wehle D, Tavora F, Looijenga L, Kowalski J, Zhang Z, Rosenbaum E: DNA methylation profiles delineate epigenetic heterogeneity in seminoma and non-seminoma. Br J Cancer 2012, 106(2): 414-423.

- Pierce JL: The Role of HNF4A in Germ Cell Tumor Development. Pierce-dissertation 2017.

- Cantante M, Miranda-Gonçalves V, Tavares NT, Guimarães R, Braga I, Maurício J, Acosta AM, Henrique R, Jerónimo C, Lobo J et al: Differential expression of metabolic enzymes in testicular germ cell tumors: The impact of glycolytic metabolism in embryonal carcinoma histotype. Andrology 2024, Epub ahead of print.

- Nauman M, Leslie S: Nonseminomatous testicular tumors. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025.

- Gregory Jr JJ, Finlay JL: α-Fetoprotein and β-human chorionic gonadotropin: Their clinical significance as tumour markers. Drugs 1999, 57(4): 463-467.

- Ramanathan S, Bertolotto M, Freeman S, Belfield J, Derchi LE, Huang DY, Lotti F, Markiet K, Nikolic O, Ramchandani P et al: Imaging in scrotal trauma: a European Society of Urogenital Radiology Scrotal and Penile Imaging Working Group (ESUR-SPIWG) position statement. Eur Radiol 2021, 31(7): 4918-4928.

- Hinz S, Schrader M, Kempkensteffen C, Bares R, Brenner W, Krege S, Franzius C, Kliesch S, Heicappel R, Miller K et al: The role of positron emission tomography in the evaluation of residual masses after chemotherapy for advanced stage seminoma. J Urol 2008, 179(3): 936-940.

- Koschel SG, Wong L-M: Radical inguinal orchidectomy: the gold standard for initial management of testicular cancer. Transl Androl Urol 2020, 9(6): 3094.

- Beccari T, Albi E, Chiurazzi P, Ceccarini MR: Omics sciences in the personalization of diagnosis and therapy. Clin Ter 2023, 174(2): 6.

- Batool A, Karimi N, Wu X-N, Chen S-R, Liu Y-X: Testicular germ cell tumor: a comprehensive review. Cell Mol Life Sci 2019, 76(9): 1713-1727.

- Heidenreich A, Srivastava S, Moul J, Hofmann R: Molecular genetic parameters in pathogenesis and prognosis of testicular germ cell tumors. Eur Urol 2000, 37(2): 121-135.

- Facchini G, Rossetti S, Berretta M, Cavaliere C, D'Aniello C, Iovane G, Mollo G, Capasso M, Della Pepa C, Pesce L et al: Prognostic and predictive factors in testicular cancer. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2019, 23(9): 3885-3891.

- Morales-Grimany R, Giannikou K, Delgado C, Pandit K, Baky F, Amini A, Yuen K, Gerald T, Badia R, Taylor J et al: Molecular Features and Actionable Gene Targets of Testicular Germ Cell Tumors in a Real-World Setting. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26(18): 8963.

- Kalavska K, Schmidtova S, Chovanec M, Mego M: Immunotherapy in testicular germ cell tumors. Front Oncol 2020, 10: 573977.

- Singla N, Bagrodia A, Baraban E, Fankhauser CD, Ged YM: Testicular germ cell tumors: a review. JAMA 2025, 333(9): 793-803.

- Zhang J, Campion S, Catlin N, Reagan WJ, Palyada K, Ramaiah SK, Ramanathan R: Circulating microRNAs as promising testicular translatable safety biomarkers: current state and future perspectives. Arch Toxicol 2023, 97(4): 947-961.

- Chovanec M, Lauritsen J, Bandak M, Oing C, Kier GG, Kreiberg M, Rosenvilde J, Wagner T, Bokemeyer C, Daugaard G: Late adverse effects and quality of life in survivors of testicular germ cell tumour. Nat Rev Urol 2021, 18(4): 227-245.

- Bagrodia A, Haugnes HS, Hellesnes R, Dabbas M, Millard F, Nappi L, Daneshmand S, Kollmannsberger C, Einhorn LH: Key Updates in Testicular Cancer: Optimizing Survivorship and Survival. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2025, 45(3): e472654.

- Groll R, Warde P, Jewett M: A comprehensive systematic review of testicular germ cell tumor surveillance. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2007, 64(3): 182-197.

- Eugeni E, Arato I, Del Sordo R, Sidoni A, Garolla A, Ferlin A, Calafiore R, Brancorsini S, Mancuso F, Luca G: Fertility preservation and restoration options for pre-pubertal male cancer patients: current approaches. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13: 877537.

- Schepisi G, De Padova S, De Lisi D, Casadei C, Meggiolaro E, Ruffilli F, Rosti G, Lolli C, Ravaglia G, Conteduca V et al: Psychosocial issues in long-term survivors of testicular cancer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019, 10: 447043.

- Nestler T, Schoch J, Belge G, Dieckmann K-P: MicroRNA-371a-3p—the novel serum biomarker in testicular germ cell tumors. Cancers 2023, 15(15): 3944.

- Wistuba II, Gelovani JG, Jacoby JJ, Davis SE, Herbst RS: Methodological and practical challenges for personalized cancer therapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2011, 8(3): 135-141.

- Fung C, Dinh Jr P, Ardeshir-Rouhani-Fard S, Schaffer K, Fossa SD, Travis LB: Toxicities associated with cisplatin‐based chemotherapy and radiotherapy in long‐term testicular cancer survivors. Adv Urol 2018, 2018(1): 8671832.

- Jain KK: Biomarkers of cancer. In: The handbook of biomarkers. Epub ahead of print., edn.: Springer; 2017: 273-462.

- Leao R, Albersen M, Looijenga LH, Tandstad T, Kollmannsberger C, Murray MJ, Culine S, Coleman N, Belge G, Hamilton RJ et al: Circulating MicroRNAs, the next-generation serum biomarkers in testicular germ cell tumours: a systematic review. Eur Urol 2021, 80(4): 456-466.

- Yazbeck V, Alesi E, Myers J, Hackney MH, Cuttino L, Gewirtz DA: An overview of chemotoxicity and radiation toxicity in cancer therapy. Adv Cancer Res 2022, 155: 1-27.

Annals of urologic oncology

p-ISSN: 2617-7765, e-ISSN: 2617-7773

Copyright © Ann Urol Oncol. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License.

Copyright © Ann Urol Oncol. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License.

Submit Manuscript

Submit Manuscript