Review Article | Open Access

Targeting Cellular Senescence in Prostate Cancer: Molecular Landscape and Therapeutic Avenues

Haneen Hossam1, Bandar Alattaibi1

1Faculty of Pharmacy, Yarmouk University, Shafiq Ershaidat Street, Irbid, 21163, Jordan.

Correspondence: Bandar Alattaibi (Faculty of Pharmacy, Yarmouk University, Shafiq Ershaidat Street, Irbid, 21163, Jordan; Email: al.attaibi98981@gmail.com).

Annals of Urologic Oncology 2026, 9: 2. https://doi.org/10.32948/auo.2026.01.25

Received: 25 Dec 2025 | Accepted: 28 Jan 2026 | Published online: 07 Feb 2026

Key words prostate cancer, senescence, SASP, therapy-induced senescence, senolytics, senomorphics

The poor prognosis linked to advanced disease in prostate cancer is, in part, due to the development of resistance to treatment via both androgen receptor-dependent and androgen receptor-independent signaling, one of which is cancer cell senescence, which receives growing interest [7]. Preclinical models and other clinical samples of prostate cancer have shown that senescence is induced by numerous different forms of anticancer therapy, including chemotherapy, targeted therapy, androgen receptor inhibitor, PARP inhibitor, and radiation therapy [8]. The senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) is a distinctive biological phenotype represented by flattened and enlarged cell morphology, and release of a complex pattern of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines collectively known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) [9].

Although senescence has originally been identified as a natural phenomenon and process related to aging and as a protective mechanism against malignant transformation, there is an ever-growing body of literature that indicates that senescence can, at times, play a role in disease progression and immune escape [10]. It is worth noting that the tumor microenvironment can be altered to support long-term proliferative signaling, angiogenesis, and replicative immortality by SASP factors, which increases therapeutic resistance and disease progression [11]. Senescent cancer cells re-enter the cell cycle to cause disease relapse, which therapy-induced senescence permits cancer cells to avoid cell death when they are exposed to cytotoxic therapy, including chemotherapy and radiation [7]. Senescence has become a major concern of modern cancer studies due to its dynamic and possibly reversible character [11]. Given its correlation with aggressive tumor behavior and resistance to treatment, it is important to have a complete understanding of therapy-induced senescence so as to come up with more effective therapy methods. This review outlines the existing evidence regarding the therapeutic value of therapy-induced senescence in mediating therapy resistance and also addresses the new strategies focused on the selective elimination of senescent tumor cells.

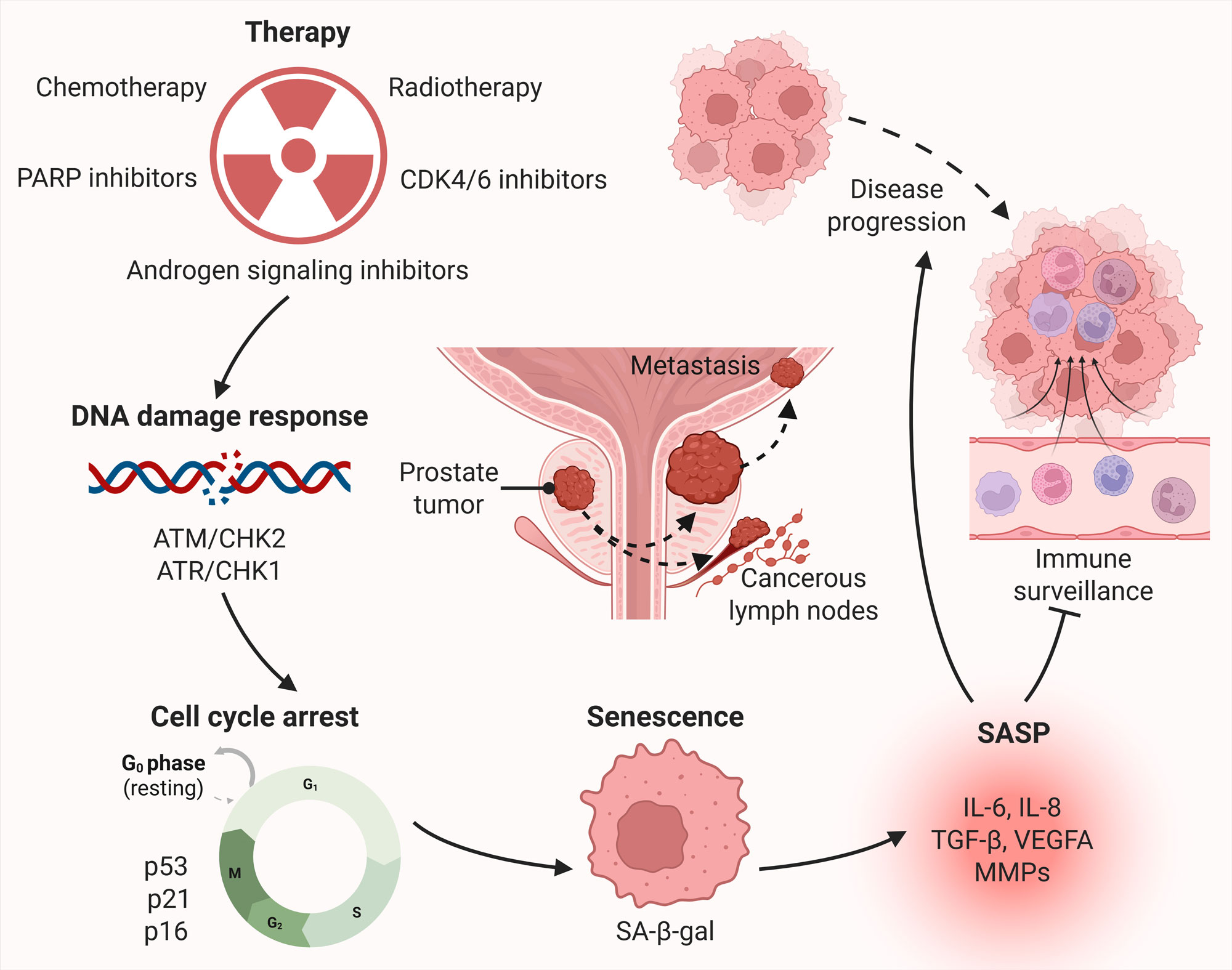

In patients with mCRPC, taxanes, in particular, docetaxel, continue to be a central player as chemotherapy. These agents destabilize microtubule dynamics and therefore disrupt the metaphase-to-anaphase transition and cause mitotic arrest. Experimental research has shown that the use of docetaxel leads to a senescent phenotype in prostate cancer cell lines [12]. In addition, treatment with docetaxel was linked with strong senescence stimulation and only moderate antitumor immune activation in a PTEN-knockout mouse model of prostate cancer [13]. Chemotherapeutic agents based on platinum, which are frequently employed in mCRPC, have been reported to cause senescence associated with G2/M cell cycle arrest via activation of the p53/p21 or p16 signaling pathways [14]. Likewise, the structural damage of DNA, which is induced by alkylating agents, is characterized by the introduction of alkyl groups to guanine residues and results in the blockage of the cell cycle and cell-surviving senescence processes (Figure 1) [8, 15]. Besides having a direct impact on tumor cells, chemotherapeutic agents may trigger the process of senescence in non-malignant stromal cells, such as fibroblasts, and, as a result, reorganize the tumor microenvironment. Examination of prostate cancer tissues from patients has depicted that taxane-based treatment is linked with an increase in senescence-associated markers [16]. In line with these observations, conditioned media prepared using senescent human prostate fibroblasts under the influence of docetaxel can substantially increase metastatic spread of prostate cancer, and therefore, the role of stroma in therapy-induced senescence and associated tumor progression is significant [16]. These results suggest that senescence induced by chemotherapy can lead to treatment resistance in prostate cancer.

Exposure of stromal fibroblasts and prostate epithelial cells to ionizing radiation results in upregulation of senescence-associated markers, such as p16INK4a and SA-β-gal. This is accompanied by a SASP, with increased levels of inflammatory and matrix-remodeling factors [17]. Such SASP elements may induce proliferation of surrounding unirradiated cells through activation of pro-survival signaling pathways, such as ERK1/2, and pro-growth signaling pathways, such as AKT, and subsequently promote tumor repopulation and disease progression [17]. Prostate cancer cell lines, which survive after administration of fractionated ionizing radiation, have been reported to acquire a senescence-like phenotype and can re-enter the cell cycle after radiation exposure is stopped, underscoring the reversibility of radiation-induced senescence [18]. Genetic factors associated with tumors determine the propensity of radiation to cause senescence. Prostate cancer cells that maintain p53 signaling function seem to be more susceptible to senescence following DNA damage by radiation [19]. These findings have increasing clinical implications, considering the broader application of radiopharmaceutical therapies that emit β particles, such as 177Lu-PSMA, and newer α-particle-emitting radiotracers, including 225Ac-based radioligands, in the treatment of advanced prostate cancer [20]. These results confirm that senescence caused by radiotherapy can markedly promote therapy resistance in prostate cancer.

The use of androgen receptor inhibitors and inhibitors of androgen biosynthesis is considered to be an essential part of the management of prostate cancer. Even though a number of patients achieve a prolonged clinical response with androgen deprivation therapy, disease recurrence and progression to castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) are common with this treatment [21]. There are several mechanisms that have been postulated to cause resistance to androgen deprivation therapy, including changes in the androgen receptor signaling axis. Other contributory signaling involves lineage plasticity and activation of other survival programs, such as PI3K-AKT and Wnt signaling cascades [22]. It has been experimentally demonstrated that androgen deprivation results in increased senescence-associated markers, such as SA-β-galactosidase, p27, and heterochromatin protein 1 gamma (HP1γ), in androgen-dependent LNCaP cells and in mouse xenografts made of such cells [23]. On a regular basis, Myc-Cap bicalutamide-sensitive prostate cancer cells display typical senescent phenotypes, including distorted cell morphology, high levels of SA-β-gal activity, cathepsin D accumulation, and expression of SASP-associated factors [24]. Mechanistically, androgen deprivation is reported to inhibit S-phase kinase-associated protein 2 (SKP2) expression and enhance the expression of cell cycle inhibitory proteins, thereby inducing a senescence growth arrest in prostate cancer cells [25]. These results are clinically relevant, as patient tissue studies indicate a strong increase in the senescence marker GLB1 in prostate tumors of those who are exposed to androgen deprivation therapy, when compared to those who are not [26]. Repeated cycles of androgen deprivation have also been reported to give rise to androgen-refractory cell populations. Notably, the growth arrest in these cells can be reversed, because when normal androgen levels are restored, these cells are able to resume the cell cycle, and once more, they proliferate [24]. This phenotype has, over time, been found to be linked to augmented resistance to chemotherapy and increased stimulation of pro-survival signaling cascades, as well as inhibition of p53-dependent apoptotic pathways [27]. These results indicate that senescence caused by androgen signaling inhibitors can significantly contribute to the emergence of therapy resistance in prostate cancer.

PARP inhibitors induce defects in homologous recombination DNA repair pathways. Although PARP inhibitor have proven to be effective in the treatment of prostate cancer, resistance is a common occurrence, and continued research is being carried out to develop mechanisms that can either overcome or delay resistance to therapy [28]. It has been demonstrated by preclinical studies that PARP inhibitor treatment induce senescence through G2/M checkpoint and activation of the p53-dependent cell cycle arrest. Importantly, the senescent phenotype can be reversed by withdrawal of PARP inhibitor, which shows that there is a risk of tumor recurrence due to the remaining senescent cell population [29]. Other than their action on tumor cells, PARP inhibitor may also cause senescence in the tumor microenvironment, especially fibroblasts. It has been demonstrated that senescent fibroblasts stimulate proliferation of hormone-sensitive as well as hormone-resistant prostate cancer cells, while simultaneously inhibiting the expansion of natural killer cells and associated cytotoxicity in vitro [30]. These results imply that senescence induced by PARP inhibitors can significantly contribute to resistance against treatments aiming to cure prostate cancer.

Abemaciclib, palbociclib, ribociclib, and other cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 (CDK4/6) inhibitors exert antitumor activity by blocking the transition between the G1 and S phases of the cell cycle, and such inhibition relies on the function of the RB protein as well as cyclin D signaling [31]. CDK4/6 inhibitors have yet to reveal significant clinical benefit in prostate cancer clinical trials. A randomized phase II trial comparing palbociclib plus androgen deprivation therapy to androgen deprivation therapy alone in prostate cancer patients showed no significant differences in clinical outcomes [32]. Likewise, abemaciclib together with abiraterone did not enhance outcomes in patients with mCRPC [33]. Resistance mechanisms include compensatory activation of the cyclin E1-CDK2 axis, loss of essential tumor suppressors, such as RB and PTEN, and increased signaling via PI3K or MAPK pathways [4, 5]. Besides these processes, therapy-induced senescence has emerged as an additional possible source of the limited efficacy of CDK4/6 inhibitors. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that abemaciclib therapy leads to disease stabilization but does not result in complete tumor regression, followed by recovery of tumor cell proliferation over time [34]. On a molecular scale, palbociclib has been found to upregulate p16, p21, and p53, which collectively induce a senescent state in prostate cancer cells (Figure 1) [35]. In addition, CDK4/6 inhibition is capable of activating the cGAS-STING pathway, which further enhances the induction of senescence [36]. CDK4/6 inhibitors can also cause senescence in stromal constituents of the tumor microenvironment. It has been demonstrated that senescent fibroblasts induced by CDK4/6 inhibitors facilitate the development of metastatic behavior and suppress antitumor immune responses, creating an environment conducive to tumor growth [37]. These results affirm that senescence induced by CDK4/6 inhibitors can promote resistance against therapeutic treatments in prostate cancer.

Figure 1. Therapy-induced senescence and associated tumor progression in prostate cancer. Therapies, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, androgen deprivation therapy, PARP inhibitors, and CDK4/6 inhibitors, induce DNA damage and replication stress, leading to activation of the DNA damage response. Persistent DNA damage response signaling activates tumor suppressor pathways involving p53/p21 and p16, resulting in stable cell cycle arrest and entry into a senescent state. Senescent tumor cells exhibit characteristic features such as increased senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) activity, and actively secrete a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), composed of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IL-8), chemokines, growth factors (e.g., VEGF, TGF-β), and matrix-remodeling enzymes (MMPs). SASP factors act in autocrine and paracrine manners to promote tumor cell survival and disease progression by stimulating angiogenesis, enhancing invasion and metastasis, and evading immune surveillance.

Figure 1. Therapy-induced senescence and associated tumor progression in prostate cancer. Therapies, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, androgen deprivation therapy, PARP inhibitors, and CDK4/6 inhibitors, induce DNA damage and replication stress, leading to activation of the DNA damage response. Persistent DNA damage response signaling activates tumor suppressor pathways involving p53/p21 and p16, resulting in stable cell cycle arrest and entry into a senescent state. Senescent tumor cells exhibit characteristic features such as increased senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) activity, and actively secrete a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), composed of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IL-8), chemokines, growth factors (e.g., VEGF, TGF-β), and matrix-remodeling enzymes (MMPs). SASP factors act in autocrine and paracrine manners to promote tumor cell survival and disease progression by stimulating angiogenesis, enhancing invasion and metastasis, and evading immune surveillance.

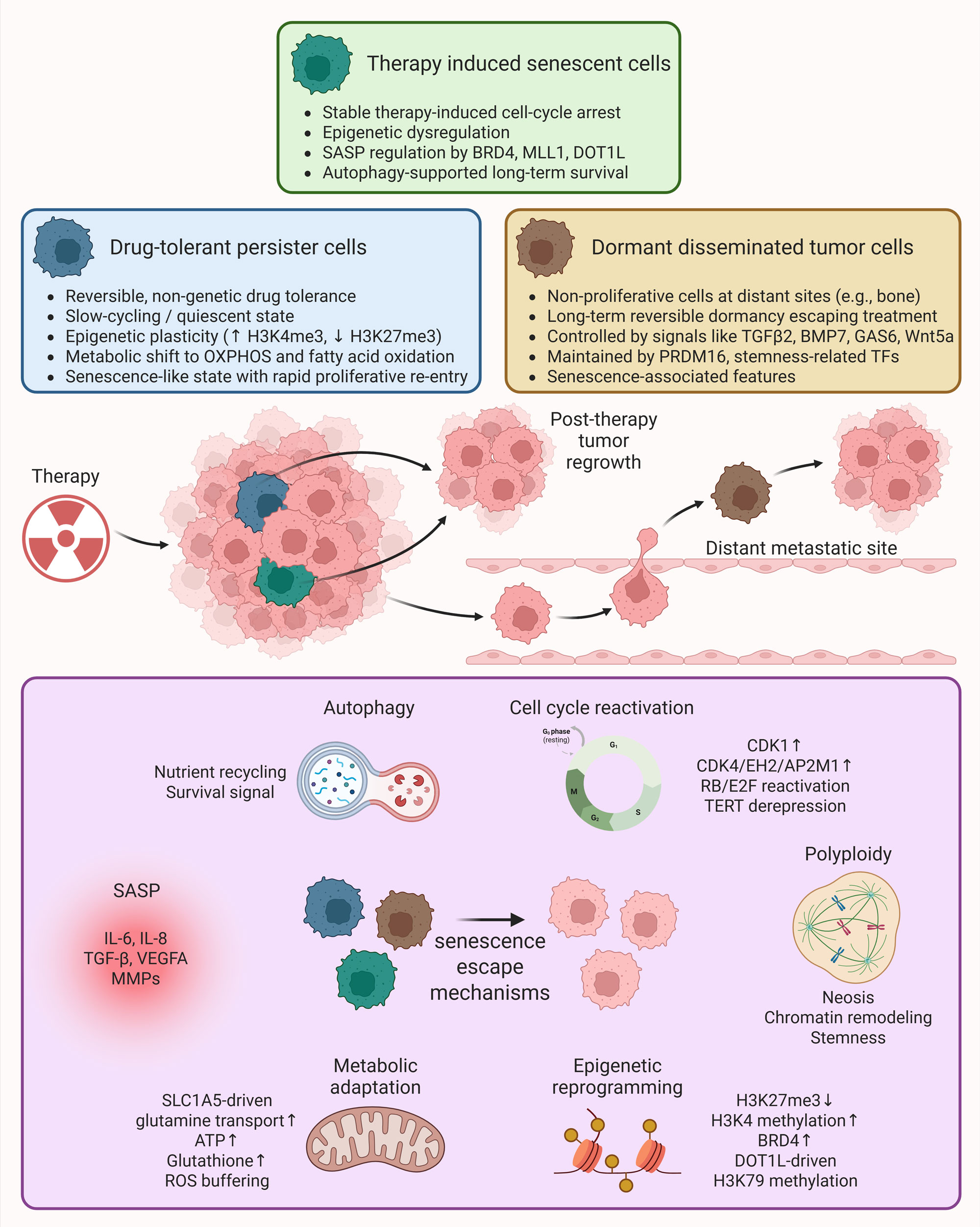

Dormant disseminated tumor cells are inactive prostate cancer cells, which detach and settle in remote anatomic locations, and maintain a non-proliferative state (Figure 2) [57]. These cells are able to endure long after initial treatment, thus escaping therapies that specifically target actively dividing cells [58]. Under certain biological or microenvironmental stimuli, dormant disseminated tumor cells may exit dormancy, re-enter the cell cycle, and trigger late metastatic recurrence [58, 59]. Dormancy maintenance in dormant disseminated tumor cells is regulated by both intrinsic cellular programs and extrinsic microenvironmental signals. Intrinsically, PRDM16 upregulation obstructs cell cycle progression by constraining RB/E2F signaling, thereby promoting a dormant phenotype [60]. Other intrinsic regulators include increased post-translational modification of histone H3 and higher transcriptional activity of SOX2, SOX9, NANOG, and NR2F, which promote long-term dormancy maintenance [57]. The bone microenvironment is a critical player in regulating dormancy of these cells. TGFβ2 and GDF10, secreted by osteoblasts, induce dormancy by stimulating the TGFβRIII/p38 MAPK pathway and regulating the phosphorylation state of RB [61]. BMP7 released by bone stromal cells has been reported to induce dormancy through stimulation of p21 and the metastasis suppressor gene NDRG1 in prostate cancer cells [62]. Growth arrest-specific protein 6 (GAS6), an osteoblast-secreted Axl receptor tyrosine kinase-binding protein, activates G1 arrest and exerts anti-apoptotic effects during chemotherapy in prostate cancer cells [63]. In addition, β-catenin is inhibited by osteoblast-derived Wnt5a via the Wnt5a/ROR2/SIAH2 signaling cascade, maintaining dormancy of these cells in prostate cancer [64]. Overall, dormant disseminated tumor cells are believed to occupy a predominantly dormant state, since they retain the capacity to re-enter proliferation in a reversible manner in response to appropriate stimuli [65]. Nevertheless, their ability to remain inactive over long periods indicates participation of mechanisms that sustain long-term and stable growth arrest [66]. This long-term survival is characteristic of cellular senescence, including continued production of SASP and dependence on autophagy [67]. Disseminated tumor cells can transition into a senescent state under therapeutic pressure or microenvironmental stress, and that senescent tumor cells can also acquire dormancy-related properties and disseminate to distant sites [66].

A complex interaction between microenvironmental signals and intrinsic cell programs, such as epigenetic changes, controls the dynamic switch between dormant disseminated tumor cell state and therapy-induced senescence [66]. It is more probable that dormant disseminated tumor cells that later acquire the capacity to proliferate and initiate metastatic growth originate from a senescent population, as SASP factors actively stimulate re-entry into an actively proliferating state [68]. Initiation and maintenance of therapy-induced senescence are heavily regulated by epigenetic pathways, which impose a stable cell cycle arrest. At the same time, expression of SASP factors is under epigenetic control through BRD4 binding to acetylated histone H3 at lysine 27 (H3K27ac), mixed-lineage leukemia 1 (MLL1)-mediated histone H3K4 methylation, and disruptor of telomeric silencing 1-like (DOT1L)-mediated histone H3K79 methylation, respectively [69, 70]. Cellular senescence has traditionally been considered an irreversible, terminal growth arrest. Nonetheless, a growing body of evidence indicates that therapy-induced senescence can be reversible under certain cancer conditions, and, even though senescence escape is relatively rare, it can represent a critical mechanism leading to tumor recurrence and disease progression. Among the well-defined mechanisms of senescence escape is the upregulation of CDK1 that induce the development of polyploid senescent cells [71]. These polyploid cells may undergo neosis to generate progeny that can re-enter the cell cycle [72, 73]. Polyploidy has been associated with chromatin remodeling, acquisition of stem-like features, and resistance to therapy, thereby enabling escape from senescence and progression to a more aggressive phenotype [74]. Other pathways facilitating senescence evasion include activation of the Cdk4/EZH2/AP2M1 pathway and derepression of TERT gene [75]. Metabolic responses also play a significant role, as higher levels of SLC1A5 transported produce increased ATP and glutathione, mitigating reactive oxygen species, whereas glutamine-deficient cells are unable to exit senescence (Figure 2) [76].

Senescence enables cancer cells to endure otherwise lethal therapeutic and immune-mediated stresses through avoidance of apoptosis. Because senescence can be reversed, populations of malignant tumor cells can be regenerated through re-entry into the cell cycle [48]. Tumor cells that escape senescence generally do not retain permanent genetic resistance to the original therapy, and often display drug sensitivities comparable to treatment-naïve cells. However, epigenetic plasticity may promote acquisition of stem-like characteristics that confer enhanced proliferative and tumor-initiating capacity [10]. Over time, this population may accumulate additional genetic alterations, giving rise to tumor clones with stable resistance phenotypes [77, 78]. Consequently, persistence of senescent cells following therapy may contribute to aggressive tumor evolution, late recurrence, and metastatic progression in prostate cancer.

Figure 2. Role of senescence-associated therapy resistant cell states in prostate cancer. Following anticancer therapy, a small population of tumor cells survives as minimal residual disease, consisting of heterogeneous therapy-resistant states including therapy-induced senescent cells, drug-tolerant persister cells, dormant disseminated tumor cells, and stem-like cancer cells. These cells enter a growth arrest (reversible or irreversible) but remain metabolically active and resistant to apoptosis, while continuously producing SASP factors that remodel the tumor microenvironment. When conditions are favorable post-therapy, these cells escape senescence through various mechanisms including cell cycle reactivation, polyploidy, epigenetic reprogramming, metabolic adaptation, SASP-driven signaling and autophagy, and repopulate the primary or metastatic sites, contributing to aggressive tumor evolution and therapeutic failure.

Figure 2. Role of senescence-associated therapy resistant cell states in prostate cancer. Following anticancer therapy, a small population of tumor cells survives as minimal residual disease, consisting of heterogeneous therapy-resistant states including therapy-induced senescent cells, drug-tolerant persister cells, dormant disseminated tumor cells, and stem-like cancer cells. These cells enter a growth arrest (reversible or irreversible) but remain metabolically active and resistant to apoptosis, while continuously producing SASP factors that remodel the tumor microenvironment. When conditions are favorable post-therapy, these cells escape senescence through various mechanisms including cell cycle reactivation, polyploidy, epigenetic reprogramming, metabolic adaptation, SASP-driven signaling and autophagy, and repopulate the primary or metastatic sites, contributing to aggressive tumor evolution and therapeutic failure.

An increasing number of senolytics, especially those that interact with BCL family anti-apoptotic proteins, are in clinical studies as cancer therapy [79]. In spite of this interest, the use of senolytics in prostate cancer is still restricted to preclinical trials. Navitoclax (ABT-263) is a senolytic that binds to anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family proteins, such as BCL-2, anti-apoptotic BCL-w, and BCL-xL. Navitoclax causes mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and the intrinsic apoptotic pathway to be activated by inhibiting BCL-xL [80]. Despite the clinical performance of navitoclax in the hematologic malignancies, its single agent performance in solid tumours has been of limited effectiveness [81]. However, preclinical trials have demonstrated that when used in combination with senescence causing therapies, navitoclax is capable of killing senescent cancer cells [82, 83]. Navitoclax used with the combination of either docetaxel or paclitaxel reinstated apoptotic sensitivity in taxane-resistant prostate cancer cells [84]. Co-treatment of navitoclax with enzalutamide increased drug sensitivity in resistant prostate cancer cells and led to increased tumor regression in an androgen receptor inhibitor-resistant mouse model [85]. Nevertheless, the senescence induced by the therapy had never been clearly verified before the administration of navitoclax in those studies [85]. In a PTEN/TIMP1-knockout mouse, senescence was induced by the use of docetaxel, but the metastatic spread was encouraged, whereas the simultaneous presence of navitoclax eliminated senescent cells and lowered the metastatic spread to the lungs and kidneys. Navitoclax monotherapy also eradicated senescent cells and inhibited the metastatic colonization [86]. Although this leads to positive preclinical results, a phase II clinical trial of navitoclax in patients with mCRPC was prematurely stopped because of slow-patient accrual [87]. Besides, clinical applicability of navitoclax has been restricted by dose-limiting thrombocytopenia caused by on-target inhibition of BCL-xL within platelets [88].

Venetoclax (ABT-199), BCL-2-selective inhibitor, platelet-sparing was developed to overcome toxicity issues. Venetoclax has been shown to have significant clinical effect in hematologic malignancies but little activity when used in solid tumors as monotherapy [89]. Venetoclax and enzalutamide combination therapy in enzalutamide-resistant prostate cells boosted apoptotic cell death and slowed tumor growth [90]. Its combination with cisplatin increased sensitivity of cisplatin and decreased colony development in prostate cancer cells [91]. These studies did not pre-evaluate therapy-induced senescence before administering venetoclax. A phase Ib study is in progress to assess venetoclax and enzalutamide combination in patients with refractory mCRPC [92]. Sabutoclax (BI-97C1) is a pan-inhibitor of BCL-2 family proteins. In preclinical experiments, it has been demonstrated that sabutoclax causes apoptosis and decreases the tumor burden in castration-resistant prostate cancer models. Sabutoclax with docetaxel improved the sensitivity of the latter and decreased tumor volume in a combination treatment over that of docetaxel alone [93]. MCL-1 is also becoming a relevant target of senolytic therapy. Selective MCL-1 inhibitor, S63845, was found to be more effective in eliminating senescent cells as compared to navitoclax in prostate cancer models after senescence induction either with palbociclib or with docetaxel [94]. In an in vivo study, S63845 was sequentially administered following senescence induced by docetaxel, and this treatment minimized the metastatic load and restored antitumor immunity [94]. Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) have also become a source of interest to increase specificity of senolytic delivery. Mirzotamab clezutoclax (ABBV-155), an anti-B7-H3 antibody with a BCL-xL inhibitor payload attached, showed antitumor efficacies in combination with taxane chemotherapy in highly pretreated patients [95]. These findings have underlined the possibility of incorporating senolytic approaches with existing therapy and novel treatment regimens.

Senomorphics suppress the adverse outcomes of the SASP by inhibiting key signaling pathways, including NF-κB, mTOR, and JAK/STAT signaling [40]. Senomorphics can inhibit tumor-promoting inflammation, restrain cancer cell growth, and limit the ability of senescent cells to affect neighboring cells in the tumor microenvironment by suppressing SASP production and disrupting SASP-mediated paracrine signaling [41]. Metformin, an mTOR inhibitor, is one of the senomorphic agents that has been studied. In a prostate cancer model, metformin therapy after androgen deprivation therapy decreased the growth of androgen deprivation therapy-induced senescence and inhibited tumor growth [96]. Senescent fibroblast-conditioned media stimulated the proliferation of prostate cancer cells, whereas metformin decreased NF-κB signaling and associated tumor growth [97]. Other mTOR inhibitors, including rapamycin, have also been reported to exert senomorphic activity. Rapamycin reduces SASP cytokine secretion, thereby suppressing NF-κB activation-mediated inflammatory pathways [98]. Additionally, senomorphic effects have been reported for adapalene, which is a retinoic acid receptor agonist. Its combination was associated with reprogramming of the SASP toward a tumor-suppressive phenotype, as well as increased recruitment of antitumor natural killer (NK) cells [99]. Although senomorphics demonstrate therapeutic potential, they may require continuous administration to maintain suppression of SASP activity, thereby increasing the likelihood of adverse effects and potentially promoting chronic inflammation or immunosuppression, which could accelerate tumor progression [100]. Overall, senolytics and senomorphics present potent therapeutic modalities to overcome senescence-related therapy resistance in prostate cancer.

Clinical application of senolytics in future in prostate cancer management as adjuncts to conventional therapies that induce senescence can be landmark advancement. However, several challenges must be addressed prior to widespread clinical implementation, including identification of optimal drug combinations, establishment of acceptable safety profiles, and identification of patient populations most likely to benefit [101]. Current preclinical models are limited by inconsistent confirmation of senescence prior to senolytic administration and incomplete evaluation of senescent cell clearance following treatment. Additionally, heterogeneity in senescence phenotypes complicates the development of universal biomarkers of therapy-induced senescence, making it difficult to identify senescent tumors and assess therapeutic efficacy [8]. One of the major concerns associated with senolytic therapy is the presence of senescent cells in non-malignant tissues, raising the risk of off-target toxicity. Although elimination of senescent non-cancerous cells has mitigated certain toxicities in preclinical models, dose-limiting adverse effects, such as thrombocytopenia and neutropenia, remain challenges, particularly with BCL-2/BCL-xL inhibitors [41]. Development of senolytic-containing antibody-drug conjugates, along with intermittent dosing schedules, represents potential strategies to enhance selectivity and reduce toxicity. As the safety, specificity, and clinical applicability of senescence-targeting therapies continue to improve, senolytics and senomorphics may ultimately become integral components of individualized treatment strategies for prostate cancer.

Non applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this publication.

Author contributions

Haneen Hossam designed the work, collected data, and drafted the article. Bandar Alattaibi revised the draft manuscript and approved the final submission.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Funding

None.

- Sekhoacha M, Riet K, Motloung P, Gumenku L, Adegoke A: Prostate Cancer Review: Genetics, Diagnosis, Treatment Options, and Alternative Approaches. Molecules 2022, 27(17): 5730.

- Baude J, Caubet M, Defer B, Teyssier CR, Lagneau E, Créhange G, Lescut N: Combining androgen deprivation and radiation therapy in the treatment of localised prostate cancer: Summary of level 1 evidence and current gaps in knowledge. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol 2022, 37: 1-11.

- Sundi D, Tosoian JJ, Nyame YA, Alam R: Outcomes of very high-risk prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy: Validation study from 3 centers. Cancer 2019, 125(3): 391-397.

- Henríquez I, Roach M, 3rd, Morgan TM: Current and Emerging Therapies for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer (mCRPC). Biomedicines 2021, 9(9): 1247.

- Varaprasad GL, Gupta VK, Prasad K, Kim E, Tej MB, Mohanty P, Verma HK, Raju GSR, Bhaskar L, Huh YS: Recent advances and future perspectives in the therapeutics of prostate cancer. Exp Hematol Oncol 2023, 12(1): 80.

- Freedland SJ, Davis M, Epstein AJ, Arondekar B: Real-world treatment patterns and overall survival among men with Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer (mCRPC) in the US Medicare population. Prostate Cancer prostatic dis 2024, 27(2): 327-333.

- Bacca L, Brandariz J, Zacchi F, Zivi A, Mateo J, Labbé DP: Therapy-induced senescence in prostate cancer: mechanisms, therapeutic strategies, and clinical implications. Gene 2025, 972: 149774.

- Wang L, Lankhorst L: Exploiting senescence for the treatment of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2022, 22(6): 340-355.

- Ohtani N: The roles and mechanisms of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP): can it be controlled by senolysis? Inflamm Regen 2022, 42(1): 11.

- Milanovic M, Fan DNY, Belenki D, Däbritz JHM, Zhao Z, Yu Y, Dörr JR, Dimitrova L, Lenze D, Monteiro Barbosa IA et al: Senescence-associated reprogramming promotes cancer stemness. Nature 2018, 553(7686): 96-100.

- Dong Z, Luo Y, Yuan Z, Tian Y, Jin T, Xu F: Cellular senescence and SASP in tumor progression and therapeutic opportunities. Mol Cancer 2024, 23(1): 181.

- Schutz FA, Buzaid AC, Sartor O: Taxanes in the management of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: efficacy and management of toxicity. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2014, 91(3): 248-256.

- Toso A, Revandkar A, Di Mitri D, Guccini I, Proietti M, Sarti M, Pinton S, Zhang J, Kalathur M, Civenni G et al: Enhancing chemotherapy efficacy in Pten-deficient prostate tumors by activating the senescence-associated antitumor immunity. Cell Rep 2014, 9(1): 75-89.

- Rutecki S, Pakuła-Iwańska M, Leśniewska-Bocianowska A, Matuszewska J, Rychlewski D, Uruski P, Stryczyński Ł, Naumowicz E, Szubert S, Tykarski A et al: Mechanisms of carboplatin- and paclitaxel-dependent induction of premature senescence and pro-cancerogenic conversion of normal peritoneal mesothelium and fibroblasts. J Pathol 2024, 262(2): 198-211.

- Funakoshi D, Obinata D, Fujiwara K, Yamamoto S, Takayama K, Hara M, Takahashi S, Inoue S: Antitumor effects of pyrrole-imidazole polyamide modified with alkylating agent on prostate cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2022, 623: 9-16.

- Pardella E, Pranzini E: Therapy-Induced Stromal Senescence Promoting Aggressiveness of Prostate and Ovarian Cancer. Cells 2022, 11(24): 4026.

- Jiang S, Song CS, Chatterjee B: Stimulation of Prostate Cells by the Senescence Phenotype of Epithelial and Stromal Cells: Implication for Benign Prostate Hyperplasia. FASEB Bioadv 2019, 1(6): 353-363.

- Kyjacova L, Hubackova S, Krejcikova K, Strauss R, Hanzlikova H, Dzijak R, Imrichova T, Simova J, Reinis M, Bartek J et al: Radiotherapy-induced plasticity of prostate cancer mobilizes stem-like non-adherent, Erk signaling-dependent cells. Cell Death Differ 2015, 22(6): 898-911.

- Karnwal A, Dutta J, Aqueel Ur R, Al-Tawaha A, Nesterova N: Genetic landscape of cancer: mechanisms, key genes, and therapeutic implications. Clin Transl Oncol 2025, 28(2): 424-445.

- Sartor O, de Bono J, Chi KN, Fizazi K, Herrmann K, Rahbar K, Tagawa ST, Nordquist LT, Vaishampayan N, El-Haddad G et al: Lutetium-177-PSMA-617 for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med 2021, 385(12): 1091-1103.

- Harris AE, Metzler VM, Lothion-Roy J, Varun D, Woodcock CL, Haigh DB, Endeley C, Haque M, Toss MS, Alsaleem M et al: Exploring anti-androgen therapies in hormone dependent prostate cancer and new therapeutic routes for castration resistant prostate cancer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13: 1006101.

- Obinata D, Takayama K, Inoue S, Takahashi S: Exploring androgen receptor signaling pathway in prostate cancer: A path to new discoveries. Int J Urol 2024, 31(6): 590-597.

- Zhuang D, Kang J, Luo H, Tian Y, Liu X, Shao C: ARv7 promotes the escape of prostate cancer cells from androgen deprivation therapy-induced senescence by mediating the SKP2/p27 axis. BMC Biol 2025, 23(1): 66.

- Carpenter V, Saleh T, Min Lee S, Murray G, Reed J, Souers A, Faber AC, Harada H, Gewirtz DA: Androgen-deprivation induced senescence in prostate cancer cells is permissive for the development of castration-resistance but susceptible to senolytic therapy. Biochem Pharmacol 2021, 193: 114765.

- Kumar R, Sena LA, Denmeade SR, Kachhap S: The testosterone paradox of advanced prostate cancer: mechanistic insights and clinical implications. Nat Rev Urol 2023, 20(5): 265-278.

- Blute ML, Jr., Damaschke N, Wagner J, Yang B, Gleave M, Fazli L, Shi F, Abel EJ, Downs TM, Huang W et al: Persistence of senescent prostate cancer cells following prolonged neoadjuvant androgen deprivation therapy. PLOS One 2017, 12(2): e0172048.

- Ewald JA, Desotelle JA, Church DR, Yang B, Huang W, Laurila TA, Jarrard DF: Androgen deprivation induces senescence characteristics in prostate cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Prostate 2013, 73(4): 337-345.

- Carneiro BA, Collier KA, Nagy RJ, Pamarthy S, Sagar V, Fairclough S, Odegaard J, Lanman RB, Costa R, Taxter T et al: Acquired Resistance to Poly (ADP-ribose) Polymerase Inhibitor Olaparib in BRCA2-Associated Prostate Cancer Resulting From Biallelic BRCA2 Reversion Mutations Restores Both Germline and Somatic Loss-of-Function Mutations. JCO Precis Oncol 2018, 2: PO.17.00176.

- Lombard AP, Armstrong CM, D’Abronzo LS, Ning S: Olaparib-Induced Senescence Is Bypassed through G2-M Checkpoint Override in Olaparib-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 2022, 21(4): 677-685.

- Kamii M, Kamata R, Saito H, Yamamoto G, Mashima C, Yamauchi T, Nakao T, Sakae Y, Yamamori-Morita T, Nakai K et al: PARP inhibitors elicit a cellular senescence mediated inflammatory response in homologous recombination proficient cancer cells. Sci Rep 2025, 15(1): 15458.

- Adon T, Shanmugarajan D, Kumar HY: CDK4/6 inhibitors: a brief overview and prospective research directions. 2021, 11(47): 29227-29246.

- Palmbos PL, Daignault-Newton S: A Randomized Phase II Study of Androgen Deprivation Therapy with or without Palbociclib in RB-positive Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2021, 27(11): 3017-3027.

- Smith M, Piulats J, Todenhöfer T, Lee JL, Arija JA, Mazilu L, Azad A, Alonso-Gordoa T, McGovern U, Choudhury A et al: Abemaciclib plus abiraterone in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (CYCLONE 2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2025, 26(11): 1489-1500.

- Brandariz J, de Llobet L: Harnessing Senolytics and PARP Inhibition to Expand the Antitumor Activity of CDK4/6 Inhibitors in Prostate Cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 2025, 24(12): 1959-1976.

- Czajkowski K, Herbet M, Murias M, Piątkowska-Chmiel I: Senolytics: charting a new course or enhancing existing anti-tumor therapies? Cell Oncol (Dordr) 2025, 48(2): 351-371.

- Yang H, Wang H, Ren J, Chen Q, Chen ZJ: cGAS is essential for cellular senescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114(23): E4612-e4620.

- Guan X, LaPak KM, Hennessey RC, Yu CY, Shakya R, Zhang J, Burd CE: Stromal Senescence By Prolonged CDK4/6 Inhibition Potentiates Tumor Growth. Mol Cancer Res 2017, 15(3): 237-249.

- Ngoi NY, Liew AQ, Chong SJF, Davids MS, Clement MV, Pervaiz S: The redox-senescence axis and its therapeutic targeting. Redox Biol 2021, 45: 102032.

- Rossi M, Abdelmohsen K: The Emergence of Senescent Surface Biomarkers as Senotherapeutic Targets. Cells 2021, 10(7): 1740.

- Jin C, Liao S, Lu G, Geng BD, Ye Z, Xu J, Ge G, Yang D: Cellular senescence in metastatic prostate cancer: A therapeutic opportunity or challenge (Review). Mol Med Rep 2024, 30(3): 162.

- Saleh T, Greenberg EF: A Critical Appraisal of the Utility of Targeting Therapy-Induced Senescence for Cancer Treatment. Cancer Res 2025, 85(10): 1755-1768.

- Chambers CR, Ritchie S, Pereira BA: Overcoming the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP): a complex mechanism of resistance in the treatment of cancer. Mol Oncol 2021, 15(12): 3242-3255.

- Méndez-Clemente A, Bravo-Cuellar A, González-Ochoa S, Santiago-Mercado M, Palafox-Mariscal L, Jave-Suárez L, Solorzano-Ibarra F, Villaseñor-García M, Ortiz-Lazareno P, Hernández-Flores G: Dual STAT‑3 and IL‑6R inhibition with stattic and tocilizumab decreases migration, invasion and proliferation of prostate cancer cells by targeting the IL‑6/IL‑6R/STAT‑3 axis. Oncol Rep 2022, 48(2): 138.

- Don-Doncow N, Marginean F, Coleman I, Nelson PS, Ehrnström R, Krzyzanowska A, Morrissey C, Hellsten R, Bjartell A: Expression of STAT3 in Prostate Cancer Metastases. Eur Urol 2017, 71(3): 313-316.

- Chang Q, Bournazou E, Sansone P, Berishaj M, Gao SP, Daly L, Wels J, Theilen T, Granitto S, Zhang X et al: The IL-6/JAK/Stat3 feed-forward loop drives tumorigenesis and metastasis. Neoplasia 2013, 15(7): 848-862.

- Prata L, Ovsyannikova IG, Tchkonia T, Kirkland JL: Senescent cell clearance by the immune system: Emerging therapeutic opportunities. Semin Immunol 2018, 40: 101275.

- Majewska J, Agrawal A, Mayo A: p16-dependent increase of PD-L1 stability regulates immunosurveillance of senescent cells. Nat Cell Biol 2024, 26(8): 1336-1345.

- Saleh T, Tyutyunyk-Massey L, Gewirtz DA: Tumor Cell Escape from Therapy-Induced Senescence as a Model of Disease Recurrence after Dormancy. Cancer Res 2019, 79(6): 1044-1046.

- Liu S, Jiang A, Tang F, Duan M, Li B: Drug-induced tolerant persisters in tumor: mechanism, vulnerability and perspective implication for clinical treatment. Mol Cancer 2025, 24(1): 150.

- Pu Y, Li L, Peng H: Drug-tolerant persister cells in cancer: the cutting edges and future directions. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2023, 20(11): 799-813.

- Marsolier J, Prompsy P, Durand A: H3K27me3 conditions chemotolerance in triple-negative breast cancer. Nat Genet 2022, 54(4): 459-468.

- Mancini C, Lori G, Pranzini E, Taddei ML: Metabolic challengers selecting tumor-persistent cells. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2024, 35(3): 263-276.

- Wang R, Yamada T: Transient IGF-1R inhibition combined with osimertinib eradicates AXL-low expressing EGFR mutated lung cancer. Nat Commun 2020, 11(1): 4607.

- Russo M, Chen M, Mariella E: Cancer drug-tolerant persister cells: from biological questions to clinical opportunities. Nat Rev Cancer 2024, 24(10): 694-717.

- Mikubo M, Inoue Y, Liu G, Tsao MS: Mechanism of Drug Tolerant Persister Cancer Cells: The Landscape and Clinical Implication for Therapy. J Thorac Oncol 2021, 16(11): 1798-1809.

- Kurppa KJ, Liu Y, To C, Zhang T, Fan M, Vajdi A, Knelson EH, Xie Y, Lim K, Cejas P et al: Treatment-Induced Tumor Dormancy through YAP-Mediated Transcriptional Reprogramming of the Apoptotic Pathway. Cancer Cell 2020, 37(1): 104-122.e112.

- Cackowski FC, Heath EI: Prostate cancer dormancy and recurrence. Cancer Lett 2022, 524: 103-108.

- DeMichele A, Clark AS: Targeting dormant tumor cells to prevent recurrent breast cancer: a randomized phase 2 trial. Nat Med 2025, 31(10): 3464-3474.

- Najafi M, Mortezaee K, Majidpoor J: Cancer stem cell (CSC) resistance drivers. Life Sci 2019, 234: 116781.

- Nasr MM, Wadie B: PRDM16 Regulates Prostate Cancer Cell Dormancy and Prevents Bone Metastatic Outgrowth. Cancer Res 2026, 86(3): 604-621.

- Yu-Lee LY, Yu G, Lee YC, Lin SC, Pan J, Pan T, Yu KJ, Liu B, Creighton CJ, Rodriguez-Canales J et al: Osteoblast-Secreted Factors Mediate Dormancy of Metastatic Prostate Cancer in the Bone via Activation of the TGFβRIII-p38MAPK-pS249/T252RB Pathway. Cancer Res 2018, 78(11): 2911-2924.

- Kobayashi A, Okuda H, Xing F, Pandey PR, Watabe M, Hirota S, Pai SK, Liu W, Fukuda K, Chambers C et al: Bone morphogenetic protein 7 in dormancy and metastasis of prostate cancer stem-like cells in bone. J Exp Med 2011, 208(13): 2641-2655.

- Lee E, Decker AM, Cackowski FC, Kana LA, Yumoto K, Jung Y, Wang J, Buttitta L, Morgan TM, Taichman RS: Growth Arrest-Specific 6 (GAS6) Promotes Prostate Cancer Survival by G(1) Arrest/S Phase Delay and Inhibition of Apoptosis During Chemotherapy in Bone Marrow. J Cell Biochem 2016, 117(12): 2815-2824.

- Ren D, Dai Y, Yang Q, Zhang X: Wnt5a induces and maintains prostate cancer cells dormancy in bone. J Exp Med 2019, 216(2): 428-449.

- Landum F, Correia AL: A Live Tracker of Dormant Disseminated Tumor Cells. Methods Mol Biol 2024, 2811: 155-164.

- Chiu FY, Kvadas RM, Mheidly Z, Shahbandi A, Jackson JG: Could senescence phenotypes strike the balance to promote tumor dormancy? Cancer Metastasis Rev 2023, 42(1): 143-160.

- Tonnessen-Murray CA, Frey WD, Rao SG, Shahbandi A: Chemotherapy-induced senescent cancer cells engulf other cells to enhance their survival. J Cell Biol 2019, 218(11): 3827-3844.

- Palazzo A, Hernandez-Vargas H, Goehrig D, Médard JJ, Vindrieux D, Flaman JM, Bernard D: Transformed cells after senescence give rise to more severe tumor phenotypes than transformed non-senescent cells. Cancer Lett 2022, 546: 215850.

- Capell BC, Drake AM, Zhu J, Shah PP, Dou Z, Dorsey J, Simola DF, Donahue G, Sammons M, Rai TS et al: MLL1 is essential for the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Genes Dev 2016, 30(3): 321-336.

- Leon KE, Buj R, Lesko E: DOT1L modulates the senescence-associated secretory phenotype through epigenetic regulation of IL1A. J Cell Biol 2021, 220(8): e202008101.

- Song KX, Wang JX, Huang D: Therapy-induced senescent tumor cells in cancer relapse. J Natl Cancer Cent 2023, 3(4): 273-278.

- Gosselin K, Martien S, Pourtier A, Vercamer C, Ostoich P, Morat L, Sabatier L, Duprez L, T’Kint de Roodenbeke C, Gilson E et al: Senescence-associated oxidative DNA damage promotes the generation of neoplastic cells. Cancer Res 2009, 69(20): 7917-7925.

- Zhang S, Mercado-Uribe I, Sood A, Bast RC, Liu J: Coevolution of neoplastic epithelial cells and multilineage stroma via polyploid giant cells during immortalization and transformation of mullerian epithelial cells. Genes Cancer 2016, 7(3-4): 60-72.

- Saleh T, Carpenter VJ, Bloukh S, Gewirtz DA: Targeting tumor cell senescence and polyploidy as potential therapeutic strategies. Semin Cancer Biol 2022, 81: 37-47.

- Le Duff M, Gouju J, Jonchère B, Guillon J, Toutain B, Boissard A, Henry C, Guette C, Lelièvre E, Coqueret O: Regulation of senescence escape by the cdk4-EZH2-AP2M1 pathway in response to chemotherapy. Cell Death Dis 2018, 9(2): 199.

- Yoo HC, Park SJ, Nam M, Kang J, Kim K, Yeo JH, Kim JK, Heo Y, Lee HS, Lee MY et al: A Variant of SLC1A5 Is a Mitochondrial Glutamine Transporter for Metabolic Reprogramming in Cancer Cells. Cell Metab 2020, 31(2): 267-283.e212.

- Aparicio S, Caldas C: The implications of clonal genome evolution for cancer medicine. N Engl J Med 2013, 368(9): 842-851.

- Venkatesan S, Swanton C, Taylor BS, Costello JF: Treatment-Induced Mutagenesis and Selective Pressures Sculpt Cancer Evolution. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2017, 7(8): a026617.

- Malayaperumal S, Marotta F, Kumar MM, Somasundaram I, Ayala A, Pinto MM, Banerjee A, Pathak S: The Emerging Role of Senotherapy in Cancer: A Comprehensive Review. Clin Pract 2023, 13(4): 838-852.

- Mohamad Anuar NN, Nor Hisam NS, Liew SL, Ugusman A: Clinical Review: Navitoclax as a Pro-Apoptotic and Anti-Fibrotic Agent. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11: 564108.

- Roberts AW, Advani RH, Kahl BS, Persky D, Sweetenham JW, Carney DA, Yang J, Busman TB, Enschede SH, Humerickhouse RA et al: Phase 1 study of the safety, pharmacokinetics, and antitumour activity of the BCL2 inhibitor navitoclax in combination with rituximab in patients with relapsed or refractory CD20+ lymphoid malignancies. Br J Haematol 2015, 170(5): 669-678.

- Rudin CM, Hann CL, Garon EB, Ribeiro de Oliveira M, Bonomi PD, Camidge DR, Chu Q, Giaccone G, Khaira D, Ramalingam SS et al: Phase II study of single-agent navitoclax (ABT-263) and biomarker correlates in patients with relapsed small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2012, 18(11): 3163-3169.

- Jaya I, Safriadi F, Wijaya I, Pitaloka P, Afifah E, Medina FS, Bashari MH: Role of Bcl-2 family anti-apoptosis inhibition in overcoming therapeutic resistance in prostate cancer: A systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2025, 215: 104895.

- Tamaki H, Harashima N, Hiraki M, Arichi N, Nishimura N, Shiina H, Naora K, Harada M: Bcl-2 family inhibition sensitizes human prostate cancer cells to docetaxel and promotes unexpected apoptosis under caspase-9 inhibition. Oncotarget 2014, 5(22): 11399-11412.

- Xu H, Sun Y, Huang CP, You B, Ye D, Chang C: Preclinical Study Using ABT263 to Increase Enzalutamide Sensitivity to Suppress Prostate Cancer Progression Via Targeting BCL2/ROS/USP26 Axis Through Altering ARv7 Protein Degradation. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12(4): 831.

- Guccini I, Revandkar A, D’Ambrosio M, Colucci M, Pasquini E, Mosole S, Troiani M, Brina D, Sheibani-Tezerji R, Elia AR et al: Senescence Reprogramming by TIMP1 Deficiency Promotes Prostate Cancer Metastasis. Cancer Cell 2021, 39(1): 68-82.e69.

- Carpenter V, Saleh T, Chakraborty E, Min Lee S, Murray G, Reed J, Souers A, Faber AC, Harada H, Gewirtz DA: Androgen deprivation-induced senescence confers sensitivity to a senolytic strategy in prostate cancer. Biochem Pharmacol 2024, 226: 116385.

- Ploumaki I, Triantafyllou E, Koumprentziotis IA: Bcl-2 pathway inhibition in solid tumors: a review of clinical trials. Clin Transl Oncol 2023, 25(6): 1554-1578.

- Kawakatsu R, Tadagaki K, Yamasaki K, Yoshida T: Venetoclax efficacy on acute myeloid leukemia is enhanced by the combination with butyrate. Sci Rep 2024, 14(1): 4975.

- Liang Y, Jeganathan S, Marastoni S, Sharp A, Figueiredo I, Marcellus R, Mawson A: Emergence of Enzalutamide Resistance in Prostate Cancer is Associated with BCL-2 and IKKB Dependencies. Clin Cancer Res 2021, 27(8): 2340-2351.

- Ruiz de Porras V, Wang XC, Palomero L, Marin-Aguilera M, Solé-Blanch C, Indacochea A, Jimenez N, Bystrup S, Bakht M, Conteduca V et al: Taxane-induced Attenuation of the CXCR2/BCL-2 Axis Sensitizes Prostate Cancer to Platinum-based Treatment. Eur Urol 2021, 79(6): 722-733.

- Perimbeti S, Jamroze A, Gopalakrishnan D, Jain R, Jiang C, Holleran JL, Parise RA, Bies R, Quinn D, Attwood K et al: Phase Ib study of enzalutamide with venetoclax in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2025, 95(1): 115.

- Jackson RS, 2nd, Placzek W, Fernandez A, Ziaee S, Chu CY, Wei J, Stebbins J, Kitada S, Fritz G, Reed JC et al: Sabutoclax, a Mcl-1 antagonist, inhibits tumorigenesis in transgenic mouse and human xenograft models of prostate cancer. Neoplasia 2012, 14(7): 656-665.

- Troiani M, Colucci M, D’Ambrosio M, Guccini I, Pasquini E, Varesi A, Valdata A, Mosole S, Revandkar A, Attanasio G et al: Single-cell transcriptomics identifies Mcl-1 as a target for senolytic therapy in cancer. Nat Commun 2022, 13(1): 2177.

- Carneiro BA, Perets R, Dowlati A, LoRusso P, Yonemori K, He L, Munasinghe W, Noorani B, Johnson EF, Zugazagoitia J: Mirzotamab clezutoclax as monotherapy and in combination with taxane therapy in relapsed/refractory solid tumors: Dose expansion results. J Clin Oncol 2023, 41(16_suppl): 3027-3027.

- Yang B, Damodaran S, Khemees TA, Filon MJ, Schultz A, Gawdzik J, Etheridge T, Malin D, Richards KA, Cryns VL et al: Synthetic Lethal Metabolic Targeting of Androgen-Deprived Prostate Cancer Cells with Metformin. Mol Cancer Ther 2020, 19(11): 2278-2287.

- Moiseeva O, Deschênes-Simard X, St-Germain E, Igelmann S, Huot G, Cadar AE, Bourdeau V, Pollak MN, Ferbeyre G: Metformin inhibits the senescence-associated secretory phenotype by interfering with IKK/NF-κB activation. Aging Cell 2013, 12(3): 489-498.

- Laberge RM, Sun Y, Orjalo AV, Patil CK, Freund A, Zhou L, Curran SC, Davalos AR, Wilson-Edell KA, Liu S et al: Author Correction: MTOR regulates the pro-tumorigenic senescence-associated secretory phenotype by promoting IL1A translation. Nat Cell Biol 2021, 23(5): 564-565.

- Colucci M, Zumerle S, Bressan S, Gianfanti F, Troiani M, Valdata A, D’Ambrosio M, Pasquini E, Varesi A, Cogo F et al: Retinoic acid receptor activation reprograms senescence response and enhances anti-tumor activity of natural killer cells. Cancer Cell 2024, 42(4): 646-661.e649.

- Ji S, Xiong M, Chen H, Liu Y, Zhou L, Hong Y, Wang M, Wang C: Cellular rejuvenation: molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic interventions for diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8(1): 116.

- Arai S, Jonas O, Whitman MA, Corey E, Balk SP, Chen S: Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Increase MCL1 Degradation and in Combination with BCLXL/BCL2 Inhibitors Drive Prostate Cancer Apoptosis. Clin Cancer Res 2018, 24(21): 5458-5470.

Annals of urologic oncology

p-ISSN: 2617-7765, e-ISSN: 2617-7773

Copyright © Ann Urol Oncol. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License.

Copyright © Ann Urol Oncol. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License.

Submit Manuscript

Submit Manuscript